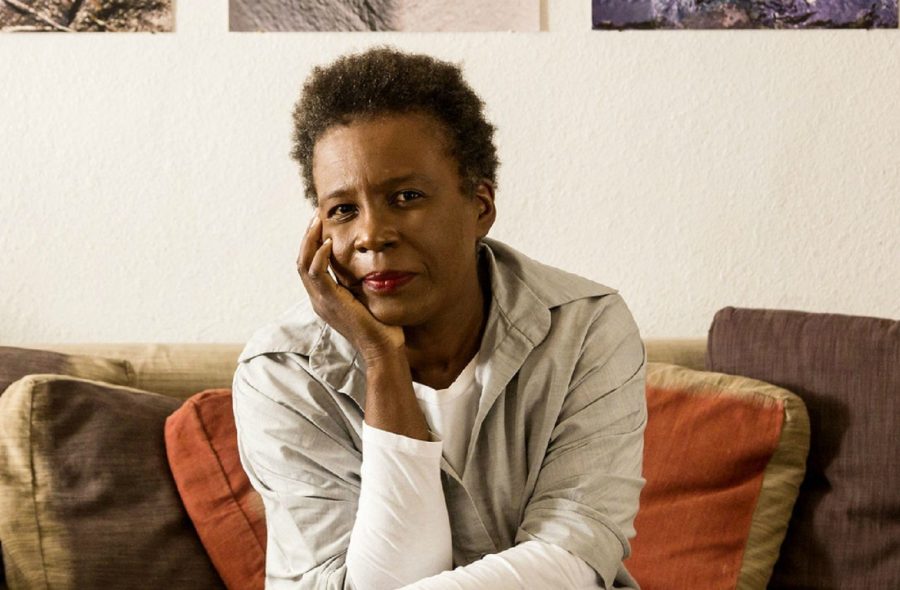

Claudia Rankine gives a poet’s insight into the nature of conversation in white America.

What is in a conversation? For renowned poet and scholar Claudia Rankine, this communicative exchange involves a reorientation of space, as well as the affective relations between those involved. These mundane exchanges that we make and observe in everyday conversation do not take place in a vacuum, but rather, are informed by political unconsciousness and the complex matrices of power that organize our social worlds.

Rankine was invited as a keynote speaker on Feb. 28 by UC San Diego’s Black Studies Project, an initiative for interdisciplinary academic exchange in the fields of African American and African diaspora studies. After being introduced onstage by Professor and BSP Director Dayo Gore, Rankine announces that she is not going to read about racial imaginaries as she had been invited to do, but nevermind — we are in the hands of a master. She instead chose to read excerpts from her upcoming book, “Just Us: An American Conversation.” Rankine outlined her work in this way: a conversation takes place, she transcribes the contents of this exchange and relays them to both a therapist and fact-checker, and finally, she collects her findings, sends them to their respective interlocutor, and asks, “did we have this conversation?”

The first conversation took place at an airport, which Rankine — citing an essay published last July in which she interrogates white men on a plane about white privilege — jokingly identified as a recurring milieu in her work. While standing in line, she overheard a loud argument between an older straight white couple, punctuated by the man’s question, “Are you stupid?” Here, the argument broke off while the couple’s hostage audience remained silent, in shock of this impropriety on display — a private exchange made public. For Rankine, the questions here are plentiful: Had everyone in this space just witnessed this violent act of beratement? Did this man really just call his presumed partner, a grown woman, stupid? What are the conditions of possibility for this man’s hubris to invite a group of strangers to take part in this spectacle of his aggression?

A second conversation took place between Rankine and a friend. This friend, who is a black mother, told Rankine of how her four-year-old child was removed from his classroom for what his white teacher described as “violent” behavior. Rankine pauses here. She invites us to think of this discursive moment and the ascription of violence to a black child. He is only four years old. The friend was on the phone with her son’s teacher, interrogating the grounds upon which her son was removed from his classroom. In justifying herself, the white teacher began to cry. Why must she defend herself against the fact of violence that she has committed against this child? What did the tears coming from a white woman signify at this moment?

Rankine relates this project to a larger question which addresses the ways in which conversations involving white people and the confrontation of whiteness are so often disrupted — and thereby recircuited in the course of its dialogue — by a refusal of fact by the parties involved. Rankine asks how we can move past the simple naming of social and political phenomena to materially reckon with whiteness when that first naming must be contested by parties unwilling to accept its truth. This is a theorization of the everyday, the suffusion of a national politic into the communicative pathways we share with friends and strangers, over the phone, and in transit; however, Rankine doesn’t have all the answers — she admits doubt in her own claims to truth, hence the fact-checker. And I recognize in my own writing of this article an immense loss in the truth of things through my forgetting of what was said specifically at this event. Limited by what I remember, having made the mistake of not taking notes, I can only relay what my memory and its interpretation of Rankine’s words — further mediated by following conversations with others and their interpretations — allows.

During the following Q&A, Rankine stated that nothing she is saying is anything new. She locates her work within a genealogy of foundational black thought, found in the works of Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, and countless others. Rankine’s words invite us to think of an academic terrain unmoored from positivist accumulation and the intellectual quest to create something new, in which the modern university is so deeply entrenched. This is not just humility, but an urge to engage in a practice of respecting those who came before us and looking for answers in what has already been said.

Image courtesy of Hill-Stead Museum.