Geisel Library’s Special Collections and Archives is home to centuries’ worth of world history. The UCSD Guardian toured the archives with Director Lynda Corey Claassen to explore the artifacts that too often go unnoticed.

Tucked away on the second floor of Geisel Library, past the tables and study rooms full of busy students, lies a trove of historical treasures. It is the UC San Diego Library Special Collections and Archives, home to a wide variety of manuscripts, artworks, films, and other artifacts dating back to as early as the 13th century.

Yet the space that houses these rare gems is rather modest. Behind an inconspicuous-looking door off a hallway lined with group study tables, you’ll find a small set of rooms with shelves full of books and art pieces and the office of Director of Special Collections Lynda Corey Claassen.

Gesturing at the shelves, Claassen stated, “These are all reference books that pertain to the Spanish civil war, then over here there’ll be a whole section about voyages to the Pacific. These aren’t necessarily rare books, but they are sort of a working library for the topics.”

After explaining that these smaller rooms are designated areas for viewing Special Collections materials, Claassen led me into the annex. Once inside, I felt a shift in the air — it was colder and drier (as the artifacts must be stored at a specific temperature and humidity for preservation purposes) but also, in more of a metaphysical sense, heavier. I felt as though I’d stepped back in time.

Hundreds of shelves nearly as tall as the ceiling seemed to stretched back for miles, chock-full of books and boxes. We strolled past them, Claassen stopping occasionally to pull an item off the shelf and show me. We looked at paintings, drafts of poems, and anthologies, all of them one-of-a-kind.

“We have a world-famous collection of early voyages to the Pacific … we have one of the largest American poetry collections in the country. There’s about 250,000 books and several mile worth of manuscripts. So there’s a lot of unique material here that doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world,” Claassen enthused.

Though Claassen has a particular fondness for the Hill Collection of Pacific Voyages,praising the atlases’ illustrations and calling them “glorious examples of publication,” she finds it difficult not to fall in love with each new addition to the archives.

“New things come in here all the time, and I’m sort of the chief curator so I acquire most of those. There [are] things that I just love personally, but if I’m doing an exhibition and start looking in some other material, I’ll find another thing that I love.”

While the annex is not open to the general public, Special Collections employees can go into the store room and retrieve artifacts that people request for. This space in Geisel is one of Special Collections’ four locations and the only one that offers public services. The other locations include Scripps Institute of Oceanography, UCLA’s Southern Regional Library Facility, and a giant warehouse three miles from campus.

Read More:

The Stuart Art Collection: Creativity in a Scientific Setting

Sudden Cuts Expose Severe Problems Within UCSD’s Dance Department

This Year in AS: Reflections with Refilwe Gqajela

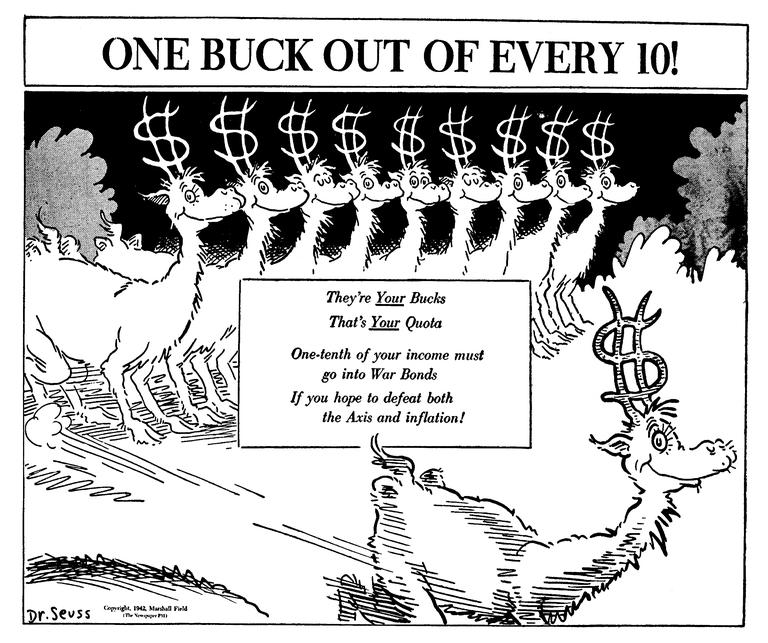

Special Collections purchased some of its artifacts but most are acquired through personal relationships and archives. The large volume of Dr. Seuss materials, for example, were donated to the university directly by his family.

“Dr. Seuss lived here in La Jolla for 45 years, and he and his wife were very interested in the development of UCSD. Before UCSD existed, he had put some of his earlier drawings in UCLA. Then, right before he passed away, he wanted all of his materials here. Everything that was at his house, which was the majority of it, is here now.”

Each year, Special Collections curates an exhibit of Dr. Seuss’ work in celebration of his birthday. Outside of these regular exhibits, which can be viewed in the display cases on the library’s second floor, Special Collections also partners with local organizations to curate exhibits. The university recently contributed about 25 volumes to an exhibit at the Mingei International Museum in Balboa Park named “Voluminous Art,” which celebrates the art of the book and bookmaking.

Each year, Special Collections curates an exhibit of Dr. Seuss’ work in celebration of his birthday. Outside of these regular exhibits, which can be viewed in the display cases on the library’s second floor, Special Collections also partners with local organizations to curate exhibits. The university recently contributed about 25 volumes to an exhibit at the Mingei International Museum in Balboa Park named “Voluminous Art,” which celebrates the art of the book and bookmaking.

Students and faculty can also access Special Collections materials to support their research. Certain humanities classes, such as Professor Mark G. Hanna’s “The Golden Age of Piracy,” even require students to use Special Collections materials in their coursework.

“[Special Collections] here at UCSD was really created to help support various academic departments,” Claassen remarked.

“So modern Spain, for example, has always been a big focus of the history department here, and that’s still true, so we have the world’s largest collection on the Spanish civil war.”

Another way for students to get involved with Special Collections is through its Undergraduate Curating Opportunity. Launched in 2017, the program allows students to use Special Collections materials to research an area of their choice, then design an exhibit to be displayed throughout Spring Quarter.

“We were trying to think of new ways of enriching the student experience, which is one of the visions of UCSD, and we came up with [the Undergraduate Curating Opportunity],” Claassen recounted.

“It was a way to introduce some students to a small part of [Special Collections] and let them work with those unique materials in a different way than they might have been able to in their regular coursework.”

This year, there are two student exhibits: Warren College senior Jorge Arana and John Muir College senior Rebecca Chhay’s “Tijuana: The View from the North” examines cross-border relations with Tijuana while Carlisle Boyle’s “Preserving History in the Pursuit of Science” focuses on J. Edward Hoffmeister’s expeditions to the South Pacific.

Chhay related, “It was just so rewarding to see people actually be interested in our exhibit. Most people go to the library with a set plan to study or work on something, but even these super goal-oriented people stop to look at the exhibits. It’s a great way for students to see the space in a different light.”

Fostering a growing sense of familiarity between Special Collections and the student body is something Claassen hopes to see for the institution’s future. The director noted how easy it is to go about your UCSD career without any involvement with Special Collections.

“Unless you investigate on your own or read something like this article, your [undergraduate] class requires you to use the collection, [or] you’re just curious on your own, you won’t experience this, and I wish more students would,” Claassen said.

With a campus culture that prioritizes science, technology, engineering, and math, non-humanities students are especially liable to overlook Special Collections. Claassen acknowledged that, since the archives mainly pertain to the arts and humanities, Special Collections isn’t quite as relevant to those studying the sciences.

“[The artifacts] are largely humanities materials, so the majority of the school isn’t going to be rushing over here to Special Collections. Even the [SIO] materials get used a lot by non-SIO people since SIO researchers aren’t particularly interested in the history of science.”

over here to Special Collections. Even the [SIO] materials get used a lot by non-SIO people since SIO researchers aren’t particularly interested in the history of science.”

Humanities student or not, Special Collections exists to enhance the lives of every member of the UCSD community. Like the Stuart Art Collection, it simultaneously contributes to the university’s individuality and supplements the educational experience. Claassen understood the nuances of Special Collections’ role at UCSD — it is definitely a significant part of our campus, but its purpose is less fundamental and more for enrichment.

“It’s part of what makes UCSD a distinctive institution. But with your incredibly busy schedules, when do you find the time to sort of wander around campus and explore its hidden secrets?”

Not wanting to remain a hidden secret, Special Collections has been conducting outreach and instruction efforts to further familiarize the UCSD community with its materials. It hosts the annual birthday party for Dr. Seuss, for instance, inviting visitors to experience the broad collection of his artwork. Piquing interest through events and exhibits is the first step in cultivating student engagement with Special Collections.

Claassen noted, “If students looked at the exhibitions, for example, would it kind of occur to them that, ‘Oh my gosh — those photos and other artifacts are actually here at this university?’ It must occur to some of them.”

Photos courtesy of UCSD library.