When I first began to shelter in place, the idle time made my mind turn to mush. As a high-achieving college student, I used to find solace in completing task after task. However, the ongoing pandemic interrupted my plans, from big ones I had made months in advance, to smaller ones I used to make daily. While at first I could not help but feel upset, recognizing that people are facing deeply serious and challenging problems due to COVID-19 has put things in perspective. Now, I realize that it is a privilege that my biggest worry during this time is finding something to do. Still, the frustration I and many others feel with having downtime is important to note because it stems from larger issues; American society is obsessed with productivity, which discourages students like me from taking time to relax, exacerbates mental health issues, and limits functioning.

While the solution may seem as simple as setting aside more time for ourselves, structural realities and societal pressures have taken the ability to make that decision out of people’s control. Ultimately, the idea that time must be used to produce and achieve is rooted in history. As such, systemic practices have long propagated the idea, further entrenching it into American culture. For example, the fact that workers in all sectors have workweeks of 40 hours or more shows that the workplaces normalize overwork as the standard. Moreover, the situation worsens across lines of class, race, and gender, with women more likely to hold multiple jobs, and people of color — especially women of color — more likely to work in jobs that do not offer paid leave. Thus, American work practices discourage downtime and prevent some people from having any at all.

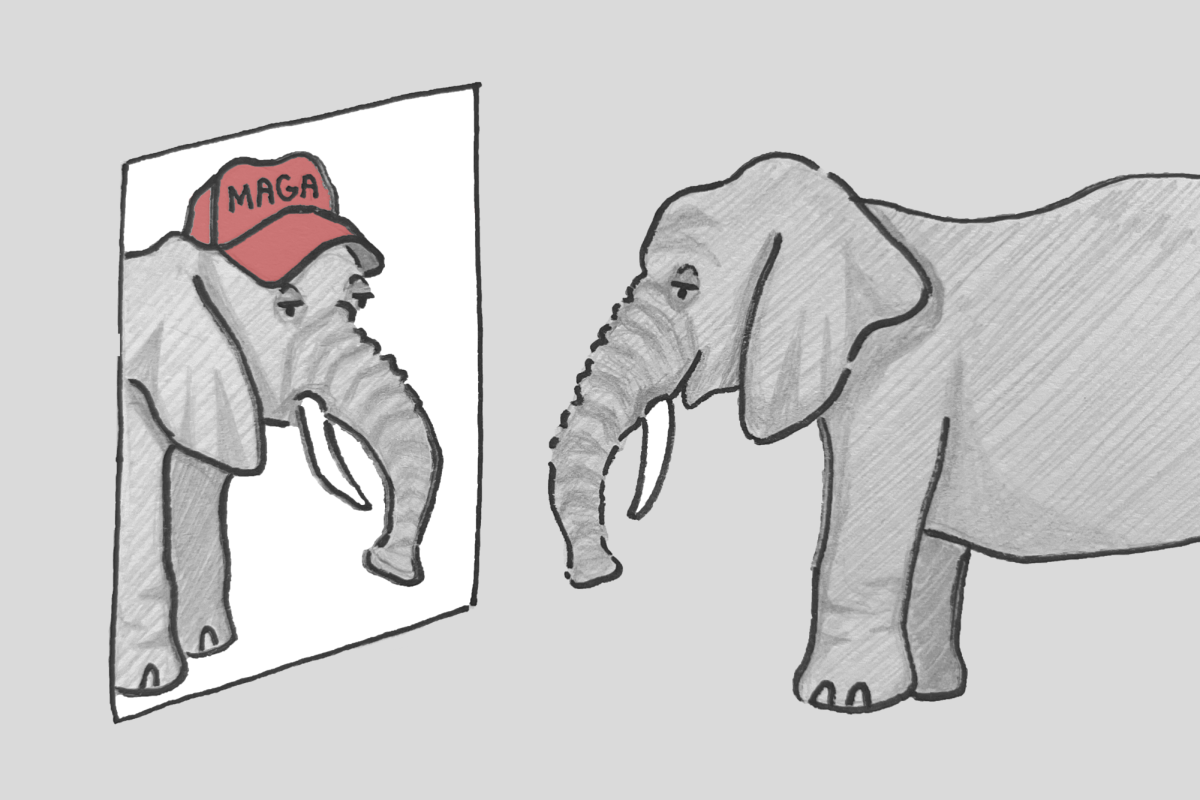

Furthermore, this deep-rooted prioritization of productivity means that even when people are not at work or school, they face pressure to achieve and perform.

Even in their free time, people feel pushed to curate their personal lives because social media commodifies them. People are spending more of their free time on their phones and for young people that means they are continuously engaged in social media. This is concerning because companies design social media applications to be addictive and mindless. However, excessive time on social media is linked to increased anxiety levels. As a result, even though engaging with social media feels as simple as idle scrolling, it is hardly relaxing. Instead, when people engage with social media, they fall into the traps of presenting their personal lives as impressively as they can and comparing themselves with the best depictions of their peers. Consequently, even people’s downtime ends up pressuring them to meet expectations.

Unfortunately, the fact that people have less true downtime has serious consequences for their health, personal growth, and happiness. For one, the pressure for productivity and increased social media usage encourages perfectionism, which is linked to depression and eating disorders. Furthermore, without downtime, people lose out on boredom. While that may not seem particularly detrimental, boredom often acts as an opportunity for individuals to check in with themselves and evaluate how they are spending their time and efforts. By doing so, people can become more mindful in their lives, comfortable in handling negative emotions and thoughts, and gain the focus necessary to restart work more effectively. Moreover, time spent away from sources of stress and external pressures is necessary to pause the blurring of days and experiences that comes from constant productivity. Ultimately, this separation is helpful because it allows people to jump-start their creativity, get in touch with themselves, and as counterintuitive as it may seem, be more productive.

Consequently, because downtime is necessary for people’s health and productivity, it is essential for societal and economic functioning. As such, society needs to stop separating people’s roles as citizens and economic actors from their humanity. Accordingly, employers need to acknowledge that their employees’ mental health is an asset to their productivity and ensure their workers have time to relax. Similarly, social media corporations need to learn that because their users’ mental health and ability to be consumers are interconnected, it is in their best interest to make sure their applications do not lead to destructive mindsets. Still, these shifts in structural attitudes and actions will take long-term collective efforts. However, while we work towards them, there are things we can do in the present to challenge the productivity-centric culture. After all, many of us are in a rare position to embrace newfound free time and, in the process of doing so, lessen the damage of a global pandemic for those who cannot afford to slow down.

Therefore, as the COVID-19 pandemic progresses, it is important to remember that having less to do is a sign of privilege. After all, countless people still cannot afford downtime and those who can often only do so at the cost of their jobs and incomes. Still, those of us that can afford free time see it negatively because of decades of messaging and a culture that encourages constant activity. Unsurprisingly, many people feel strongly about free time, with some upset they have too much of it and others longing for more. Either way, the situation reveals deep-seated problems in the way society treats the human need to relax and unwind. And right now, one way to address those issues is by slowing down, if you can, and encouraging others to do the same.

Now more than ever, letting ourselves slow down helps us and others.