Bona (1980)

Director Lino Brocka’s “Bona” should have long been regarded as a classic Filipino film. But, due to issues with preservation technology in the Philippines, the film was considered lost for over 40 years until its reappearance at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival thanks to French restoration efforts. The film follows Filipino starlet Nora Aunor, as the titular character Bona, and her infatuation with background actor Gardo (Phillip Salvador). To escape her abusive father, Bona runs away from home and moves in with Gardo, who she has grown obsessed with. She degrades herself for him, laboring day and night to meet his specific demands. Bona’s efforts are met with little to no reward, as Gardo brings home new girls every night.

In addition to its engaging plot and humorous moments, the best part of Bona, for me, was the viewing experience: sitting in a packed theater in Mira Mesa, a San Diego neighborhood best known for its large Filipino population, surrounded by Filipinos, watching a movie made by Filipinos for Filipinos. In the final scene, Bona is released from her infatuation and takes revenge on Gardo for his poor treatment of her. As she pours boiling hot water on his bare skin, the audience howled, barked, and laughed. The fact that the film has returned and can be enjoyed today is a poetic testament to culture and recognition that is enduring and accessible to those who seek it.

– Thi Tran, Contributing Writer

Living in Two Worlds (2024)

“Living in Two Worlds,” directed by Mipo O, poignantly explores the limitations of language as a vessel for meaningful communication. The film follows Dai (Ryō Yoshizawa), a child of deaf adults from Miyagi, who struggles with his identity when it clashes with his move to Tokyo, an unforgiving metropolis. In this coming-of-age story, Dai has to rediscover the pure love he knew in childhood under new stressors of conformity. Struggling with loneliness, he finds a loving community and path to peace through a sign language meeting group. In the hands of their true support, Dai sheds his desire for conformity and, instead, becomes fascinated with the unique perspectives he has gained from being raised by deaf parents.

The most transformative aspect of the film comes from Mipo O’s warm color palette. Her idyllic muted pastels, nature scenes, and golden bokehs of light blend to create liminal moments tinged with a luminosity and hope for the future — even in lachrymose scenes of despair and conflict.

By showing that silence does not equate to loneliness, “Living in Two Worlds” bravely redefines the definition of disability and the modern perspectives surrounding it, critically reshaping depictions of deafness in media. Being deaf, Mipo O shows, is not a limitation but a redirection, and the love we feel for each other is so eternal and resilient that it transcends relocation, growth pains, and transient forms of language.

– Anica Xie, Contributing Writer

Caught by the Tides (2024)

What would the end of the world look like to you? For Director Jia Zhangke, life ends not with cataclysm but a diminutive calm as our time slowly fades out. “Caught by the Tides” is Zhangke’s latest odyssey of ruptured time and cultural entropy, capturing the best and worst years in the lives of Qiao Qiao (Zhao Tao) and Guao Bin (Li Zhubin), across two decades of gentrification in 21st century China.

The film weaves documentary footage from the city of Datong into its fictional narrative, in an act of remembering what once was. Middle-aged women baring their souls to karaoke and tea, Lunar New Year celebrations filled with blisteringly joyful smiles, and streets of newspaper men and grocery shoppers going about their daily life, all formulate Zhangke’s recollection of a Datong that was jovial, grimy, and a place to call home. Simultaneously, unused sequences from Zhangke’s previous films — alongside footage shot in 2022 — form the narrative tether of “Caught by the Tides,” tracking the real-time encroachment of modernity. The lively, tight-knit depth of the communities in Datong and Guangdong Province slowly give way to a hi-fidelity, yet barren, sleekness that sees a world disconnected and disaffected, which is reflected in the aesthetics of the piecemeal footage: fuzzy and warm camcorder textures transforming into a cleanly hollow digital realm.

Watching Zhangke reckon with the melancholy of being left behind in time forced me to ponder how my own life will look one or two decades from now. Will the alienation of old age and the steely metropolitan sky consign me to loneliness? Does my death arrive when I can’t even recognize myself anymore? Only the tides of change may tell.

– Matthew Pham, Senior Staff Writer

Mahjong (1996)

In contrast to many of Edward Yang’s other works, “Mahjong” is filled with farce and is sincerely humorous. As such, the film is often not attributed the same serious consideration as “A Brighter Summer Day” or “Yi Yi,” Yang’s most widely celebrated films in the United States. Perhaps this is due to the latter two’s inclusion in the Criterion Collection and thus their relative ease of access when compared to “Mahjong,” or perhaps it has simply been discounted by critics in light of his other work.

Regardless, this is a disservice to the film; though it is a comedy, it is also an incredibly moving portrait of Yang’s trepidation about the future of Taiwan in an increasingly culturally and economically globalized world. It would be a mistake to assert that Yang is opposed to all aspects of globalization — Luen-Luen and Marthe’s relationship makes this clear — but he is wary of capitalist influence on Taiwan.

Red Fish’s father, a wealthy and notorious scammer, has accumulated a significant amount of wealth for his family, yet they are still broken and unhappy. He teaches Red Fish that, in life, people are either scammers or suckers. Because of this, Red Fish holds a delicate balance of resentment and admiration for his father, modeling his life after him while simultaneously criticizing him. The revelation that his father was unable to find happiness after all of his horrible scams drove Red Fish to despair.

Alongside Red Fish’s father, Markus, a failed British businessman, embodies Yang’s fears. Yang links the two characters through their dialogue and the film’s editing style. He leaves the screen black while Red Fish sobs, his life in shambles because of his father’s actions, before overlaying Markus’ smug laughter. Markus regurgitates the same line as Red Fish’s father: that “these people,” referring to those living in Taiwan, are happy to be told what they want. He brags about the impending colonialism of the 21st century, how happy he is to have found Taiwan, and how he has no plans of letting anyone but himself benefit from it. The level of humanity that Yang is consistently able to extract from his actors makes Markus’ heartlessness all the more striking.

Markus’ fantasization of a new era of colonialism by British and American capitalists clearly illuminates the future that Yang is so scared of. But he does not acquiesce to this, treating it as a foregone conclusion. Marthe chooses to leave the familiar comfort of Markus and instead chooses Luen-Luen, a boy who has shown her much care and consideration. It is the stark contrast in humanity between the two that leads her to this choice. The wonderful human beings are chosen over the potential accumulation of wealth and capital. With this film, Edward Yang is urging us to do the same.

– Matthew Risley, Senior Staff Writer

Shanghai Blues (1984)

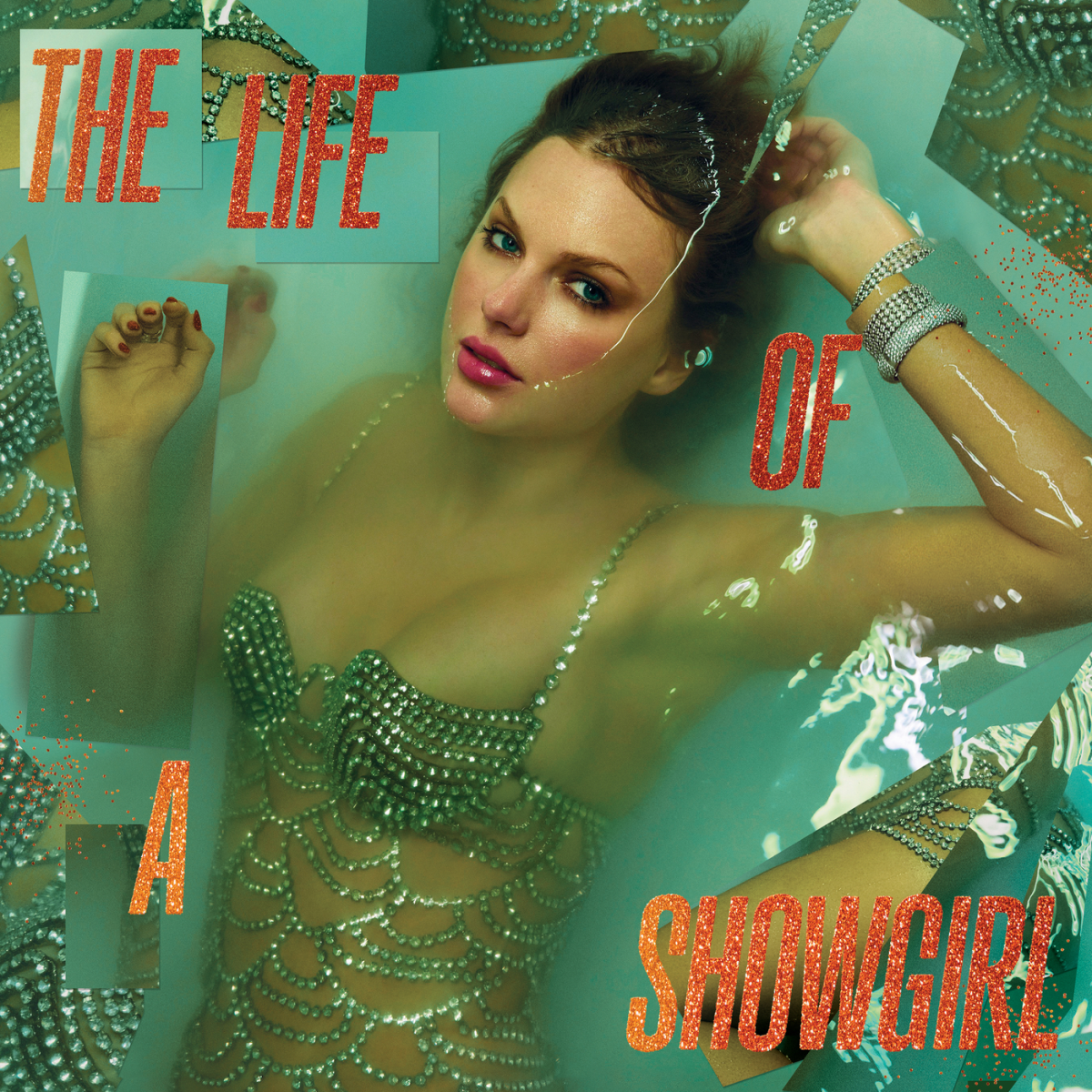

On its 40th year anniversary, Tsui Hark’s playful “Shanghai Blues” was reintroduced to the big screen with a new vibrant restoration, including a re-recording of the original Cantonese dialogue into Shanghainese and a deletion of its controversial blackface scene. Immediately, we are pulled into a showtune number at a nightclub where we find the film’s protagonist, Do-Re-Mi (Kenny Bee), in clown makeup, mulling over a decision. After leaving the club, set on enlisting as a soldier, Do-Re-Mi finds himself under a bridge beside a mysterious woman, both taking cover as bombs light up Shanghai. The two comfort each other, promising to meet again under the same bridge once the war is over.

The bulk of the film occurs 10 years after the introduction. We see Do-Re-Mi take odd jobs while attempting to promote his music; we return to the same nightclub, where Shu (Sylvia Chang) works as a showgirl, and we meet Stool (Sally Weh), who has just arrived in Shanghai. A comedic love triangle unfolds as Do-Re-Mi searches for the woman from under the bridge, with Stool’s naivete at the center of the film’s slapstick humor.

Though its lightheartedness and musicality makes for easy entertainment, “Shanghai Blues” provides a glimpse of post-war desperation that highlights the city’s lasting social disintegration following the Battle of Shanghai and the intense misogyny that arises from it. For example, the three characters’ struggle to find stable jobs; while Do-Re-Mi can get away with performing as a jack-in-the-box, which is embarrassing at worst, Shu and Stool must put their femininity on display for men’s viewership. For as much as I found myself smiling at the film’s absurdity and romanticism, I was also left slightly unsettled by the perverse male gaze and its implications on women’s bodily autonomy.

– Xuan Ly, A&E Co-Editor