“Quiz Lady”

The San Diego Asian Film Festival’s opening night was filled with excitement, joy, and fun as a crowded theater jam-packed with people gathered to watch the opening night film. Before the film began, the staff started the night with their own quiz game about SDAFF trivia with contestants and prizes, setting the stage for the film we were about to watch. Artistic Director Brian Hu said they wanted to start the festival off with something more lighthearted than the last few years, where SDAFF showcased films about COVID-19 at their opening nights. Although I really enjoyed last year’s opening night film “Bad Axe,” I can’t help but agree that “Quiz Lady” was a cute and charming film to kick off SDAFF with.

Anne Yum (Awkwafina) is a shut-in who hates her office job, loves her dog, and is obsessed with a Jeopardy-esque game show. Her monotonous life takes a turn when her estranged older sister Jenny (Sandra Oh) puts her on her favorite game show to pay off their mother’s gambling debts. Along the way, the two reconnect and build their relationship through various shenanigans. The entire film felt very genuine and heartfelt, balancing comedy and serenity in a great way. The sisters’ relationship is the focal point of the story and the heart of the film. Anne’s indifference towards Jenny and her nomadic lifestyle was fun to watch, and the chemistry between the leads was natural and flowed well. Oh and Awkwafina played off each other as if they were actually sisters. The reversal of character archetypes was refreshing to watch. Awkwafina played the opposite of her usual personality, and Oh played a character she never had before, making the film that much funnier. The writing made it work, and it helps that it was a collaborative process. Director Jessica Yu spoke about how screenwriter Jen D’Angelo, Awkwafina, Oh, and herself workshopped the script together and their shared experiences made up a lot of the film. A sense of warmth is felt through the writing and tone, which makes it more authentic and heartfelt. I’m a sucker for narratives about sisters, and this did not fail to pull on my heartstrings, but if you are looking for a fun time, you can put this on and be guaranteed a laugh.

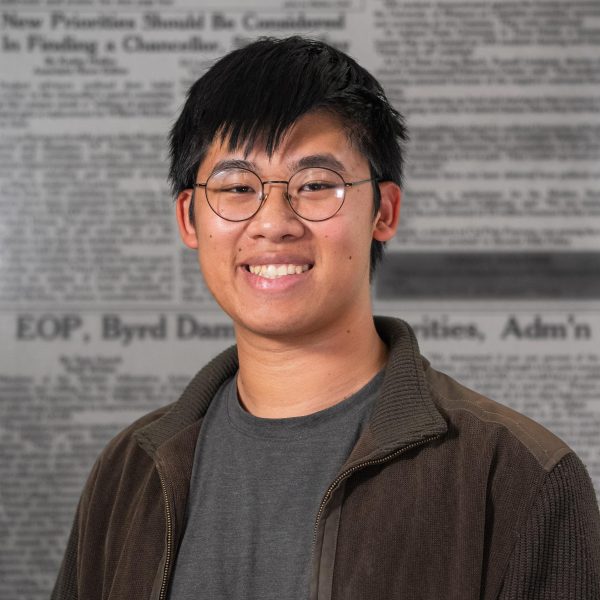

– Kamiah Johnson, A&E Co-Editor

“In Our Day”

Often when we’re in need of guidance, we turn to those who we trust to have the answers. Perhaps to those who are older, more knowledgeable, or more experienced than ourselves. We do this in search of direction, some crucial exploration to add any meaning to the tumult of our already complex, overstimulating lives. For better or worse, I’ve learned to take these lessons when I can get them. Now, enter a middle-aged former actress and a retired poet. Hong Sang-soo’s “In Our Day” places these individuals as the focal point of his story, each receiving visits from young aspiring artists. They’re asked questions regarding their careers, aspirations, and most candid opinions about life. Although they’re the ones advising, they reflect all of us who are simultaneously trying to find the answers within ourselves.

Sang-soo creates an intimate environment so serene and opposite from how the outside world can seem at times. I found myself hanging on to every last word as if I were a part of these conversations myself, even merely as a spectator. The space feels natural in a way that you forget the cameras are there at all, a credit to Sang-soo’s emblematic storytelling. “In Our Day” serves as a delightfully insightful mix of discussions touching on one of the most intricate topics: the meaning of our existence. It’s a joy to witness such a change of pace, especially one that makes you ponder its meaning long after it’s over. Those are the best kinds.

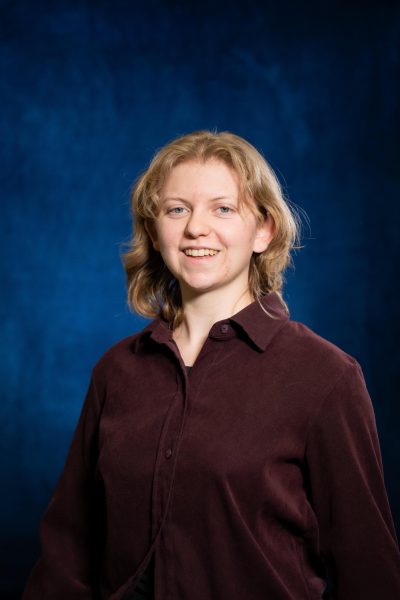

– Arshia Singh, Staff Writer

“In Our Day”: Reminders of Home

“What is it to live?”

It is a cruel question that every human grapples with at some point in their temporary lives. “In Our Day” follows the search for such knowledge through a mundane, slice-of-life film centering around two different stories founded upon questioning what lies in life’s path. The film observes two different lives: a retired Korean poet and a failed actress. Accompanying the narration of these stories is a documentary-style production that gives the audience the sense that they are stepping into these lives and intruding on their presence rather than simply watching on the screen.

As a Korean, I felt I was not just watching a movie, but engaging in an everyday setting I became familiar with in my childhood. The elderly man discussing his past experiences while complaining about needing a smoke or a drink resembled my grandfather when I would sit near his desk and try to remember to speak in a way that would not result in him scolding me. The failed actress lecturing her cousin on how to pass through a challenging situation skillfully resembled my mother, asking me to repeat what she had just said so that she knew I fully understood her words. The quaint and routineness of everyday life was an open door into my own, a world involving such monotonous topics that became the heat of conversation between my family members and me. “In Our Day” filled me with nostalgia and comfort, reminding me of my family across the globe and reminding the audience of what it truly means to live.

– Erika Myong, Staff Writer

“Evil Does Not Exist”

“Evil Does Not Exist” opens with a panning shot of barren branches overhead, stripped by the winter’s cold. From there, the audience watches Takumi, the village handyman, standing in the snow outside his house with an ax. He picks up a log from the pile on the ground and sets it carefully upright. He pulls the ax up above his head. With a swift downward swing and a thwack, the log splits down the middle.

Takumi and his daughter live in Harasawa, a small isolated community. Their life is peaceful until “glamping” (glamorous camping) company Playmode decides to build a campsite upstream. Once they call the members of the town together, the “glamping” company presents a building proposal that would contaminate the water supply, set up potential bushfires in the dry area, and disrupt local animal trails.

One of the great strengths of “Evil Does Not Exist” is director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s seamless latticework of tiny details that, when put together, form a calm and mindful community. At the town meeting, different personalities are heard. The residents of Harasawa range from a newcomer noodle shop owner to an old man who has lived in the town his entire life. Even the Playmode employees are offered a perspective. Although they arrive with little knowledge of the landscape, they take the time to consider the village’s concerns and come to their own conclusion that nature’s sacredness can only exist when we leave it alone.

Clear freshwater flows down stony creeks. Seasons change and snow drifts from the sky in flecks. Deer graze and stare back with deep black eyes. Suddenly, screeching disharmony pitches the plot off of its axis. Humans disrupt the flow of nature.

The ending of “Evil Does Not Exist” is dramatic and bewildering. The finale happens fast but also necessitates a long introspection and questioning of the world around us. In the end, viewers are forced to question the film’s title: Does evil exist? And would it still, if humans did not?

– Kaley Chun, Senior Staff Writer

Elements of Sound and Silence in “Evil Does Not Exist”

Perhaps the most highly-observed selection of the festival came in the Masters section: “Evil Does Not Exist,” Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s first feature since his highly-acclaimed work “Drive My Car” (2021) swept the world and broke countless hearts. Hamaguchi’s latest follows Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) and his daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) in the rural village of Harasawa, where their serene existence and tightly-wound community begin to unravel at the arrival of an agency planning to create glamping sites.

Immediately noticeable in the opening shot is the blinding white sky that pierces through the cavernous trees, forests that are framed as safe havens, and Eiko Ishibashi’s elegiac strings which envelop that world. At this very moment, you are safe in Harasawa. Reminiscent of Yasujiro Ozu’s elliptical shots, these opening shots are beautiful, and cinematographer Yoshio Kitagawa captures the spectral beauty of nature with wides that track across the boundless forests of this film. The lulling sense of peacefulness does not last; Ishibashi’s score is cut abruptly, and we are taken away from the haven of trees. In Harasawa, sound itself is existence. When there’s silence, sound does not exist. Silence is safety. Sound is a violation. A pin drop could disrupt the whole film. Alongside the frosty look of the film, combined with the use of sound, everything about this film is fragile. Whether through the prolonged shots of wood-cutting, the routine of picking up Hana from daycare, or even the lamentation of office work and dating apps, the film wanders into these small personal spaces that are delicate at best. In doing so, Hamaguchi finds ways to waste time away from what seems to be his thematic center: the erosion of beauty. The film’s entirety is perhaps a little too quiet, but maybe this is where evil begins to exist — we’re so distracted by the noise of everyone’s individual lives that we fail to see the larger picture. Are you listening close enough?

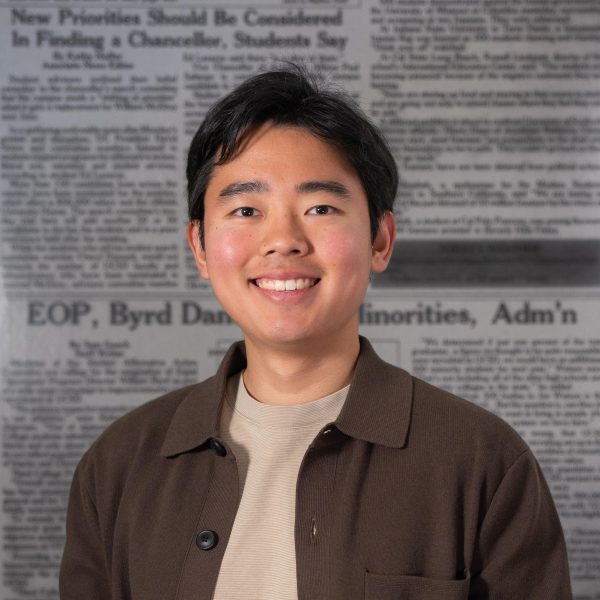

– Matthew Pham, Guest Writer

“The Accidental Getaway Driver”

Sing J. Lee’s feature directorial debut “The Accidental Getaway Driver” follows four men searching for physical, mental, and emotional liberation. During the establishing shots of Orange County’s Little Saigon, we meet Long (Hiep Tran Nghia), an elderly cab driver with sad eyes, watching his neighbors play games from a distance. When Long is called for a late night pick-up by a fellow Vietnamese man, he begrudgingly obliges. Long soon learns that his passengers are newly escaped convicts holding him hostage to help with their plans to leave the country. Adapted from a true story, Lee imbues each character with dynamic personhood, but what holds the film together is the relationship built between Tay (Dustin Nguyen), a middle-aged Vietnamese man, and Long, who comes to fill a broken father-figure role.

The words “Vietnam War” are never uttered throughout the film, but its aftermath ripples throughout the characters’ every move. With three out of four characters being Vietnamese men from different generations, it became integral that Lee convey how the impact of the war changed over time. Each of the characters had felt immense loss since their birth or rebirth in America, which became increasingly clear as their fractured relationships with family were slowly unveiled. They were confronted with parts of themselves that they kept locked away, or only knew how to handle through violence. What the men find together is comfort in understanding a small part of each other’s anger, even if that understanding is quickly lost. The desolate back roads and run-down motels of Orange County reflect the men’s self-image, and as the scenery changes to include the blue sky and a roaring ocean, the characters also see change in themselves.

– Xuan Ly, A&E Co-Editor

Image Courtesy of The San Diego Asian Film Festival