From social media manifestos to sci-fi excursions, here are five literary pieces that convey the pessimistic existentialism of the internet.

When all of our cultural consumption is curated by “for you” pages on social media apps, books are the natural alternative. Gone is the nefarious influence of the capitalist economy: readers are able to evade the subtle mind-controlling tactics of the algorithm, unimpeded by the slew of advertisements that have come to characterize online platforms. What better medium then, to explore the apocalyptic implications of life on the internet and how we have changed in response to its ubiquity? As someone who is both chronically online and an avid reader, I resort to books to help make sense of the digital spaces I occupy. Below is my literary guide to the digital apocalypse.

“An Absolutely Remarkable Thing,” Hank Green

Written by YouTube veteran and VidCon co-founder Hank Green, “An Absolutely Remarkable Thing” is an insider’s glimpse into the pitfalls of the influencer economy. The novel begins when 23-year-old April May vlogs her discovery of a sentient metal sculpture she nicknames “Carl.” What ensues is April May’s collision with the celebrity economy, as she grapples with the implications of her newfound stardom. Green’s debut novel is an exercise in self-awareness; few people understand our propensity for self-commodification as acutely as Green does. Just as April May’s fame results in unprecedented wealth for her and her friends, so too does it invite a distorted perception of self. “An Absolutely Remarkable Thing” critiques the dual-identity syndrome rampant in internet culture and reasserts our vital need for collective compassion.

“Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now,” Jaron Lanier

In his brief manifesto on digital consumption, Jaron Lanier illuminates essential truths about social media; it is making us sadder, dumber, and angrier. Lanier interrogates our time on the internet with all the graveness that it demands. To Lanier, the prevalence of social media is not just irritating — it is dooming. The algorithm has so corrupted our autonomy that we are reduced to diluted versions of our former selves, unable to distinguish our own personal tastes from that of our TikTok account’s perfected algorithm. While Lanier’s musings have a strong philosophical basis — Lanier himself is an ex-Silicon Valley tech bro, and has spent ample time reflecting on the consequences of his contributions — he offers little hope for the future of social media consumption. Indeed, Lanier’s conceptions of internet use are without imagination. Refusing to engage with others online is not a panacea for all of society’s ills, but there is a resounding truth in Lanier’s skepticism of the internet. Despite his misleading fatalism, Lanier’s core argument is indisputable: we must reevaluate how we use social media.

“No One Is Talking About This,” Patricia Lockwood

Why are we so prone to emulating the slang and rhetoric we hear on TikTok? Because, Patricia Lockwood answers, the internet has indelibly altered our lexicon. In her novel, “No One Is Talking About This,” Lockwood conveys the utter sense of disillusionment that life on the internet invites. We follow the unnamed narrator as she experiences profound personal tragedy all the while maintaining a presence on the internet. The narrator speaks the language of social media influencers: she digresses, pontificates, and accuses with all the zest of an internet microcelebrity. Through convoluted prose and a startling emulation of online vernacular, Lockwood so clearly expresses our modern dilemma — that is, the struggle to reconcile our private lives with the performative nature of social media.

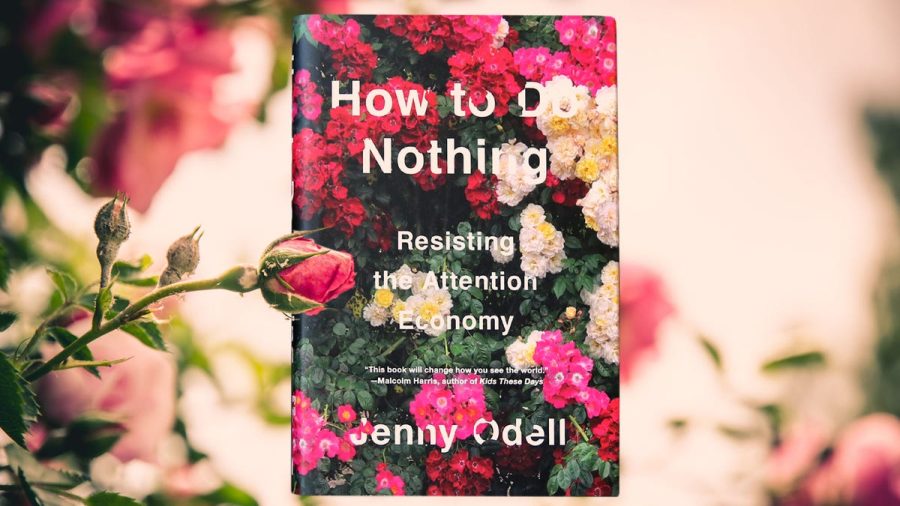

“How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy,” Jenny Odell

In a capitalist economy that rewards productivity and monetizes every facet of the human experience, doing nothing is an act of resistance. “How to Do Nothing” is both a clarion call to detach from online living and a rumination on the destructive quality of capitalism. Jenny Odell’s contemplative essays urge the importance of doing nothing in the digital age. If to be online is to abandon all pretext of geographic location and time, then situating ourselves in the physical present is a refutation of internet culture. Odell is most convincing when she settles into her key philosophy: that participating in activities outside the realm of productivity and social media fosters a more joyful existence.

“Night Sky,” Carl Dennis

Carl Dennis, in his poem “Night Sky,” renders the unfathomable as ordinary; the cosmos are not a feat of galactic proportions, but a “stream / Or a glassy roadbed or bank of flowers.” Dennis connects our existentialist fears of mundanity and worthlessness with the natural world. He asserts that our lives, however trivial, will matter as long as we engage with the world in meaningful ways. Therein lies the key to online living. We must not be subsumed by the information on our social media feeds, but be able to experience the universe as it extends itself to us.

Images Courtesy of AV Club, Medium, Picador USA on Twitter, ELLE, Time, and The Atlantic.

Alice • Feb 25, 2022 at 5:05 pm

Reading is a passion of mine, yet it has had a negative impact on my academic achievement. I am, on the other hand, used to depending on WritingJudge review sites to get the top writing services. It significantly reduces the likelihood of making a mistake in the selection, and my marks are consistently excellent.