Sometimes when reading something you wonder if people praise certain authors so as to console them for all of the suffering they must have experienced to write something so successfully sad.

“The Sarah Book” might prompt this thought if it weren’t stylishly written.

There are choices McClanahan made which make “The Sarah Book” special and which are usually not both chosen by the same writer for the same book. Someone who picked this setting probably wouldn’t have also picked this plot, and the plot of grand love stories and dramatic fallings-out is usually in tension with our ideas about the kinds of places where “The Sarah Book” is set.

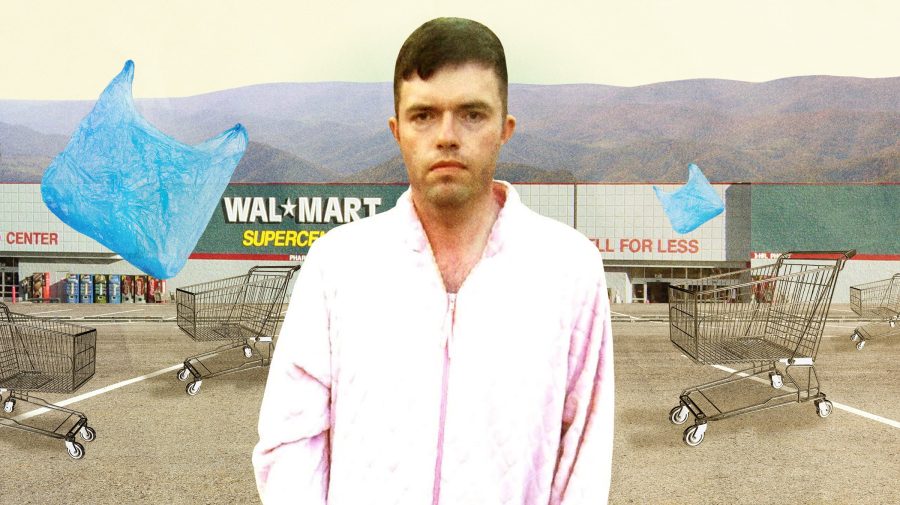

The subject matter is the stuff of “Reader’s Digest” essays and “women’s pictures.” It’s all about a divorce and a dog dying and it’s named for a woman to boot. “The Sarah Book” is set in Beckley, West Virginia, a place which both embodies and informs McClanahan’s work. Here are some of the locales and products McClanahan name-drops: Taco Bell, Fruity Pebbles, Walmart, Applebee’s, Mountain Dew, Wendy’s, Red Bull and Sarah’s black Honda CRV.

The project of “The Sarah Book” is partly to romanticize and redeem these kinds of places as locales of real despair and potential sacred temples for love and beauty. The interpersonal despair with rural chain hell as a backdrop is more meaningful than just McClanahan’s opportunity to emote. Heartbreak implies that the people who live in places like these really exist in relation to one another and are less alienated than they might be. Abandonment proves erstwhile contact and connection. It means a victory over deadened feeling and the frictionless “lonely crowd.”

When the main character, who is also named Scott McClanahan, camps out in a Walmart parking lot after being broken up with by his wife, he makes an interesting point about supermarkets. He says that for all their bleakness and fluorescence, they have everything he needs to remain alive. Looking out at some Duane Hanson sculptures come alive, he appoints himself their “emperor of soda” and their “king of beef jerky.” Later, watching the sun set over the roof of a strip mall devastated about Sarah, he says that he feels powerful for being able to find the strip mall pretty and for being able to mean it. This is the power McClanahan so nicely exercises in this book.

Infused with little lessons for survival and sentences about hideous parts of McClanahan, “The Sarah Book” is fiction as medication, fiction as self-help, and reading as a perverse kind of self-harm. It’s a book that yields little to any reader trying to figure out who exactly is a good or a bad person, like the college students in fictional Mr. McClanahan’s English classroom only ever do. The only lessons here are lessons in recognition of beauty.

Toward the end of the book, McClanahan mentions his old friend Sam with whom he used to read stories in bars in Chicago. He brings up Sam to tell us about how he once waved hello to a dog, not to be funny but because “the dog was alive and we were alive too … it was our pain that made us the same.” By writing about the extremely familiar, being upset in a parking lot, he makes himself as relatable as possible. McClanahan is “desperately waving hello” with and within “The Sarah Book.”

Because of the mention of bars, public readings and Chicago, one imagines that by “my friend Sam” McClanahan means his writer peer, the bizarro/alt-lit legend Sam Pink. There’s a great line of Pink’s that’s both in his most famous work, “Person,” and the long poem, “Your Glass Head Against the Brick Parade of Now Whats,” where he describes life as being like having “two broken hands trying to pick flowers for someone you really like.” McClanahan has picked us a bouquet of lived moments. It’s baby’s breath and red roses, but he chose those grocery-store flowers for us on purpose. He’s trying to tell us something with them.

Author: Scott McClanahan

Grade: B+

Image Courtesy of Scott McClanahan