It sounds like something from a nightmare: millions of gallons of sewage and hints of radioactive waste flowing through the water on California’s coast, with unsuspecting locals and tourists leisurely swimming through the sludge. Yet this nightmare may be very close to our current reality, if not being the very situation that California officials could someday have at hand. Just two months ago, the ocean waters from Tijuana all the way through the coastline of Southern California were stained brown with 143 million gallons of raw sewage. Last week, another (although significantly smaller) sewage spill of 1,000 gallons leaked into San Diego’s local Windansea Beach. On top of the threat of dangerously unsanitary water, the poor infrastructure of the nearby Nuclear Generating Station in San Onofre continues to pose an ominous risk of a nuclear spill into the ocean — one that could have after-effects comparable to Fukushima, Japan’s nuclear accident in 2011.

Despite these risks to our local and global waters, U.S. environmental policies have begun to collapse under the Trump Administration; environmentalists and marine scientists worry about the new threat that this lack of protection will bring to the oceans and our beaches. In an attempt to fight the forces that seem to continuously degrade global water quality, groups such as Surfrider Foundation, a San Clemente-based nonprofit environmental organization, have been campaigning for marine protection policies and awareness of the issues surrounding our oceans.

Scott Ridout, who works for a digital marketing agency as well as a volunteer as Surfrider’s No Border Sewage Committee co-chair, has been with Surfrider for about a year now. According to Ridout, the recent Tijuana sewage spill that occurred between Feb. 6 and Feb. 23 was “by far the largest raw sewage spill into the Tijuana River in over a decade.”

The sewage remained unnoted by officials until Feb. 24, when the International Boundary and Water Commission published a report confirming the 143 million gallon spill. The IBWC is essentially in charge of monitoring water quality between the U.S. and Mexican border, as well as applying boundary and water treaties between the two countries and settling any differences that may arise. The Commission completed an investigation in April regarding the Tijuana spill, but the report made no claim of any substantive changes that the Commission would make regarding their policies.

Sewage runoff from the Tijuana River into the ocean is the main reason for most beach advisories and closures across the San Diego area, as well as other Southern Californian coastal regions. Most of these closures are due to elevated levels of fecal indicator bacteria. Ridout emphasizes the need to focus on reducing pollutant discharges into the Tijuana River in order to improve this issue.

“What needs to be done to in order to reduce these pollutant discharges is to have better infrastructure within Tijuana to process [the sewage,] and also to have better regulation and oversight of what is actually being dumped into the river there,” Ridout said. “It’s not just residential areas dumping their wastewater. There’s also numerous cases of industrial waste being dumped into the Tijuana River as well. [We] need better oversight and better infrastructure to address the problem, but it’s a really lofty goal.”

Historically, Tijuana is a city that grew far too fast and never developed the necessary infrastructure to process its wastewater and sewage. After the North American Free Trade Agreement was passed in 1994, large numbers of people began moving to Tijuana in search of new economic opportunities closer to the U.S. The infrastructure of the city, however, could not keep up with the 6.69 percent increase in population between 1990 and 1995 — the largest increase recorded in Tijuana since 1960. The population of Tijuana now rests upwards of 1.7 million people, with little to no funds to improve their current infrastructure. Ridout explained that there have been few infrastructure updates since the ‘90s, and the current wastewater treatment plants simply do not have the capacity to handle the approximate 50 million gallons of sewage that is produced each day. Tijuana’s own treatment plant filters about 17 million gallons a day, and the International Wastewater Treatment Center is estimated to filter about 25 million gallons a day; the rest is left to casually overflow into the Pacific Ocean, passing right under our noses until it gets diluted.

Despite the dangers of this ocean contamination, there are still delays in announcing sewage spills and other incidents of contamination, leaving locals and tourists at risk of developing dangerous illnesses upon encountering the unclean water. The recent Tijuana spill took about two weeks before anyone was alerted despite officials being aware of the spill, and the even more recent Windansea spill still left swimmers and surfers casually diving into the sludge for hours before officials alerted them. According to Ridout, Surfrider is advocating for politicians to create concrete policies within the IBWC and the Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, which is the IBWC’s Mexican counterpart, to have daily communication regarding water quality, the flow of the Tijuana River and any sewage discharges that may have occurred.

As I entered the bustling environment of Whole Foods cafe, I spotted two more of Surfrider’s volunteers sitting collected and comfortable within the chaos of the shop. Adam Collardey and Nairin Collardey, also Surfrider’s NoBS Committee co-chairs, mentioned the importance of prioritizing improved communication on water quality as well.

“The NoBS Committee wanted the IBWC to have daily communications with a short blurb update,” Nairin Collardey said. “[Our] Policy Coordinator, Gabriela Torres, has reached out but has not gotten a lot of support for it.”

Despite Surfrider’s push for action, policy changes within the IBWC have been particularly slow in gaining momentum. “Most of the people working on this issue have common goals and [are] seeking progress on it, so I’m always wondering why there’s so little support for it,” Adam Collardey said. “Maybe it’s just the culture of the IBWC. Serge Dedina, [the mayor of Imperial Beach], asked for the head of the IBWC to step down after the sewage spill. A lot of people are so fed up with it that they’re just looking at putting pressure on [the IBWC] and whatever it takes to see improvement.”

Although the IBWC currently has policies in place to promote communication and accountability, little has been done to uphold these policies. “In the IBWC, there are Minutes, [which are] like agreements, 320 and 283, and they’re not really living up to those agreements. In those Minutes it says there’s going to be more accountability … but we need more concrete Minutes with timetables and goals,” Nairin Collardey explained to me.

Currently, most of what Surfrider is doing to address these issues revolves around education and outreach. The NoBS Committee has outlined four main policy points that it hopes will be able to improve the sewage situation. The policy points involve improved communication regarding water quality, frequent water quality testing, promoting the development of a plan to address Mexico’s deficient infrastructure and advocating for federal and state resources to stop sewage discharges into the Tijuana River.

“They’re points that are the most realistic. If we could do those four things, the situation would be a lot better,” Nairin Collardey said.

Surfrider has also been advocating for the development of a catch basin on the outskirts of Imperial Beach that would divert sewage flow and hold it until it could be treated.

“It’s a temporary solution so that it doesn’t go straight into the ocean. This is the most tangible in terms of infrastructure,” Adam Collardey said.

Mexico has also begun to create an infrastructure development plan that is estimated to take 20 years to complete; however, there is currently no financial allocation for it and, at the moment, it remains just a plan.

Regarding water-quality testing, Nairin Collardey brings up the importance of testing not just for E. coli but for other viruses, bacteria and chemicals, and to have the sand tested as well as the water.

“[It should be] ongoing, not just when there’s a spill,” she said. Since funds are currently lacking to support frequent water quality testing, Surfrider has considered bringing water testing projects to schools that could fund the projects while using the information and tests for students’ science and engineering coursework.

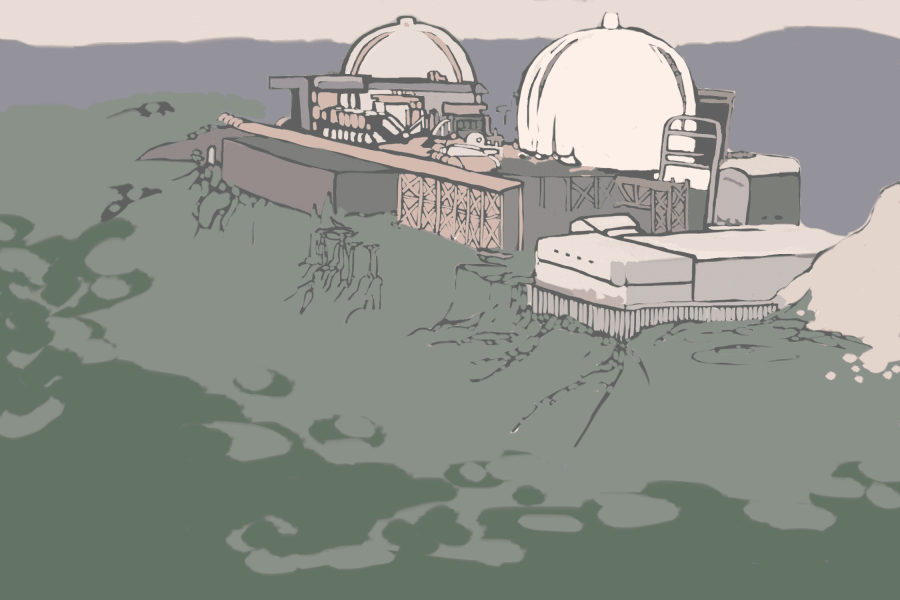

Beyond these ocean contaminants, poor infrastructure leading to sewage spills is not the only issue that the ocean faces. The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station currently holds 3.6 million pounds of radioactive waste that has been proposed by the nuclear plant’s majority owner, Southern California Edison, to be moved to a nearby storage site that sits dangerously close to two fault lines as well as the shore.

Also in Features:

Artistic Expression at UCSD || Harrison Lee

Tackling Climate Change with Playfulness || Rebecca Chong

Life in a Bollywood Dance Team: The Race to Win || Susanti Sarkar

Since there is currently no off-site relocation facility for the radioactive waste, an independent spent fuel storage installation was approved by the California Coastal Commission in October 2015, meant to operate until a new relocation site can be found. This onsite storage would be allowed until 2049, when the Federal Nuclear Regulator Commission would then be responsible for finding a potential off-site location, if one is then available. However, the approval of the on-site storage has since been challenged in court due to disagreement with how close the site will remain to the ocean. In the meantime, the waste remains a risk in its current location.

According to Mandy Sackett, Surfrider’s California Policy Coordinator, Surfrider wants to see the waste removed as soon as possible.

“There’s no question that there are better and safer locations for the material other than a populated coastline and earthquake-riddled Southern California … Our main focus right now is working to put pressure on the federal government to take swift action because they are the ones who can swiftly move this forward and, by law, are supposed to be designating a location for spent nuclear fuel.”

Current legislation in the federal congress called H.R. 474, or the Interim Consolidated Storage Act of 2017, would help create interim storage locations around the country where nuclear waste could be moved. However, Sackett points out that “there is not a timeline associated with [H.R. 474] so we’re asking for a serious mandate for a consensus-based storage siting.”

Considering the aftereffects of nuclear accidents such as that of Fukushima, Japan in 2011, moving nuclear waste away from coastlines is certainly a priority. Radioactive runoff has never stopped entering the ocean from Fukushima since the accident, meaning that there has been nonstop radioactive runoff for 2,200 days and counting. Radiation measures around the coasts near Fukushima have shown that contamination levels are higher than normal, putting humans at risk of increased rates of cancer and marine life at risk of absorbing and transmitting radioactive elements up the food chain and to humans as well. Radiation absorbed into the body has potential to cause death, cancer or genetic damage. Although radiation measurements have demonstrated that current marine life in the Fukushima area has had rather low exposure to the radiation, long-term effects of the accident and exactly how much radiation is contained in the ocean sediment are still somewhat unknown.

Although the accident in Fukushima may not be fully comparable to the situation in San Onofre, since Fukushima’s site was an active plant whereas San Onofre’s site is currently being decommissioned, the threat posed to local marine life by a nuclear spill is still very real. Adam Collardey recalls his experience in Taiwan, where he learned of the devastating effects that nuclear waste had on the local Orchid Island.

“It’s tragic. They put all this nuclear waste on this beautiful island with indigenous people and it leaks into the water and the fish are all deformed.” The locals have, in fact, claimed countless sightings of deformed fish and increased rates of cancer in their people, but little research has gone into proving the accuracy of these claims.

Despite all of the risks posed by nuclear waste and potential leakage, federal legislation remains one of the largest and only factors in determining how and where nuclear waste is stored. Trump’s recent budget proposal would provide $120 million to develop a robust interim storage program for nuclear waste, but it is a measly budget compared to the $15 billion that was necessary to build the nuclear waste storage site on Yucca Mountain in Nevada. And, unfortunately, the Trump administration continues to work toward dismantling the Environmental Protection Agency and many of its environmental protection policies.

Trump, for instance, is currently proposing cutting $250 million of funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which would cut funding for the National Estuarine Research Reserves, such as the Tijuana River Estuary. These estuaries serve as natural filtration systems for sewage before it gets released into the ocean. Without funding for these reserves, state parks would not be able to afford managing the estuaries, and the buildup of sediment would wear the estuaries away over time.

“The whole National Estuarine Research Reserves network would shut down,” Adam Collardey mentioned with concern. “All coastal management would go away. It’s pretty bad [considering] the situation [at] the border here.”

As the threats to our coasts and oceans continue to expand, Surfrider emphasizes the urgency of the situation and the dire need to address and remove these sewage and nuclear waste risks before they permanently impact marine ecosystems. Not only do officials need to begin to take these threats seriously, but local and everyday people can help bring attention to these issues as well. Through organizations such as Surfrider, people can take part in marches and beach cleanups, take on volunteer positions within the organizations, and get involved in local committee meetings. Moreover, signing action alerts such as the ones posted on Surfrider’s website can allow people to send messages to their local and federal representatives to push for actions to be made.

Nairin Collardey emphasizes how signing action alerts may not bring immediate action, but it starts a conversation and, in the long term, can lead to very successful results.

“It really makes a difference,” Adam Collardey said. “If you don’t speak up then the people who are responsible for these decisions aren’t as aware of the significance of this issue … We’re creating the starting point for what happens next.”

Despite the bleak nature of the situation regarding sewage and nuclear waste, voicing opinions as a community can ultimately make a great difference in how representatives will treat the issue. As Ridout resolutely pointed out near the end of our conversation, “I know a lot of people don’t have confidence in our political system, especially now. However, I think to do nothing would be the ultimate sacrifice.”