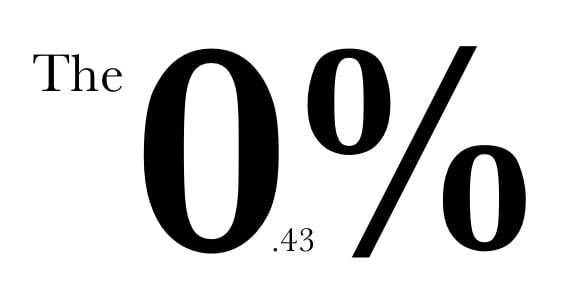

Native Americans are among the most underrepresented ethnic groups at UC San Diego. Out of the 28,127 undergraduate students enrolled during Fall Quarter of 2016, only 121 students identified as Native American.

However, the UCSD Native American community’s small numbers in no way detract from its passion for change. UCSD’s Native American Student Alliance, a student organization comprised of around a dozen undergraduates and graduates, works to educate the UCSD community on Native American issues and serves the Native American community both at UCSD and beyond.

Though the organization has dropped out of existence about four times since it was first founded 30 years ago, NASA experienced an exciting surge in growth this past year.

The year 2016 marked the grand opening of the Inter-Tribal Resource Center in Price Center West, and the welcoming of its inaugural director, Elena Hood. One of UCSD’s several campus community centers, the ITRC serves as a space for Native American students and faculty and provides the Native American community with resources for educational opportunities.

NASA’s ongoing endeavors also include direct involvement in UCSD’s academics. The organization is striving to make progressive changes to UCSD’s staff and curriculum to inform UCSD students about Native American culture.

“Since last year, NASA’s been working with the ethnic studies department and other administrators to hire Native American faculty and create a Native American studies minor,” said Brody Patterson, a Revelle College sophomore and chair of NASA. Patterson identifies as a descendant of the Cold Springs Rancheria of Mono Indians and has been a part of NASA since 2015.

He continued, “Hopefully, if everything goes well, it should be a minor here at UCSD starting in 2018.”

Another one of NASA’s recent projects is centered on positively impacting the local community. In partnership with the Student Promoted Access Center for Education and Service, members of NASA have been making trips to local schools to speak to Native American students.

“So far, we’ve been to the Viejas Reservation and native Hawaiian communities, and we’ve got some other future trips planned,” Patterson said. “We’ve been working with the students, mostly middle school to early high school, and just getting them informed about college and trying to encourage them to pursue higher education.”

To further educate both the UCSD and local communities on Native American issues, NASA took part in the Native Symposium, which took place from March 1 to March 3. Headed by Professor Justin de Leon of the ethnic studies department and sponsored in part by the ITRC, the three-day event consisted of panel discussions exploring challenges that Native Americans face today. The various panelists, who ranged from UCSD student leaders to Shoshone poet Tanaya Winder, spoke on representation in media, struggles of Native American women, dispossession and coalition building across various communities.

An opportunity for members of both the local and UCSD Native American communities to express themselves, the symposium brought awareness to recent issues affecting San Diego County’s tribes. A recurring problem for Native American communities has been government projects built on sacred land.

One such issue, which was resolved in November of last year, was the building of a garbage site at Gregory Canyon in North County. The landfill would not only have been built on top of a sacred site, but also would have contaminated the drinking water for the Pala Band of Mission Indians. After protests and court cases delayed the construction of the landfill for 25 years, the Pala Tribe finally secured victory by buying part of the land meant for the project.

Another similar instance of dispossession involves the Kumeyaay Tribe and unfortunately has yet to be resolved. The tribe is currently protesting the construction of a Navy SEAL training center south of Silver Strand State Beach, which would intrude upon a sacred Kumeyaay burial ground. Thousand-year-old Kumeyaay remains still lie beneath the proposed construction site, making the construction of the Navy base a desecration of important Kumeyaay history and culture.

“Locally, we’ve been trying to bring awareness to these issues and connecting those types of things to bigger issues like the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Patterson said in regard to the issues at Gregory Canyon and Silver Strand. “We want to show that we have issues going on in the local San Diego community. Students and faculty, both native and non-native, should be supporting the local communities and trying to help them maintain their tribal sovereignty.”

On a larger scale, NASA has also been involved in taking action against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Before the Department of the Army announced that it would reroute the pipeline in December of last year, NASA was preparing to send supplies over to the protestors and was even considering taking a trip to the reservation.

Since then, NASA has refocused its activism. With the help of A.S. Council, NASA has been calling for the University of California to stop facilitating the construction of the pipeline by divesting from companies involved in DAPL.

“We’ve been working with UC administrators to pull their investments from companies invested in DAPL, focusing on getting the UC [system] to divest from Energy Transfer Partners and the other companies that are directly working on the pipeline,” Patterson explained. “The most tangible thing we can do from a college student perspective is to get the administration to take away the money they’re investing in the pipeline.”

As for the protest against DAPL that interrupted the Spirit Night basketball game in February, Patterson claimed that, while members of the Native American community at UCSD were involved, NASA itself did not play a role in the protest.

“I would say for the people who were involved in the protest, and also other marginalized communities, that we just want our issues to be noticed by the university,” Patterson continued. “We want the university to think about what’s more important — business and investing in the pipeline, or students here who are really offended by these issues.”

Patterson stressed that, for the Native American community, attention from both UCSD administrators and students is necessary for these issues within their community to be resolved.

Read Also:

Why Chinese International Students Hate the Dalai Lama || Timothy Deng

Shouting in Silence: Protesting for Recognition of the Armenian Genocide || Susanti Sarkar

Breaking the Boundaries of Communication: Professor Daniel Hallin || Tia Ikemoto

Professor Ross Frank of the ethnic studies department further supported Patterson’s assertion. Having joined UCSD as a professor in 1992, Frank researches Native American history and culture, the majority of his work focusing on cultural change among Europeans and Natives Americans. He agrees that the UCSD community can foster progress for Native Americans through a strengthened relationship with the Native American community.

“There’s not a lot of native faculty or students, so it takes everything to have good relationships with the community,” Frank said. “We need to have a visible Native community on campus to have a good relationship with the community off campus.”

A more visible Native American community requires a more substantial population of Native Americans on campus. As previously stated, Native American students only make up a tiny percentage of the undergraduate population.

“UCSD needs to build on the undergraduate body of Native American students and hire Native faculty, and also provide curriculum on campus that will give students academic interest in Native [American] studies,” Frank said. “This, along with the recruitment and retention that the ITRC provides, will sustain and build the Native [American] community.”

Patterson further believes that, before these pressing issues of dispossession within the Native American community can be resolved, UCSD students and faculty need to acknowledge the role that Native Americans played in the history of their university.

“Students and the university itself need to acknowledge more often that we are on ancestral Kumeyaay lands that were actually stolen from these people. That’s the most important thing because, without that, we can’t even acknowledge a Native presence on this campus,” said Patterson.

In terms of visibility, the future does seem promising for the Native American community at UCSD. The aforementioned advancements within NASA and local Native American communities, coupled with the increased social concern for indigenous rights brought on by the DAPL crisis, have heightened Native Americans’ presence.

The mood was heavy on March 3, the last night of the Native Symposium, as members and allies of the Native American community gathered together in the Communidad Room, listening earnestly to UCSD’s Native American leaders discussing their experiences and concerns. One such speaker was Hood who, in addition to directing the ITRC, is a member of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe and a doctoral student in UCSD’s educational studies program researching Native American youth.

Before a solemn crowd of people concerned enough about Native American rights to gather together on a Friday night, Hood expressed her hopefulness for increased visibility and justice for Native American people as she said, through tears, “We’re still here, and we’re not going anywhere.”

Have feedback? Have a story for us to cover? Email us at [email protected]

We are currently accepting applications for new writers. Click here to apply.