The Guardian takes a (reluctant?) look back at the scary movies that left lasting marks. Whether they’ve caused traumatizing emotional wounds or psych twisting disfigurements, these films have certainly left us haunted. Even Guardians can be scared sometimes.

“The Conjuring” (2013)

Our favorite horror movies are those that make us hide under our covers and check our closets for ghosts at night. “The Conjuring” is without a doubt this kind of movie. It follows all the horror movie staples: creepy music, frightening evil spirits, surprise jump scenes, hauntings from dead people. But it also breaks some rules. Some hauntings happen during the daylight — which isn’t something often seen in horror films. “The Conjuring” follows a pair of paranormal investigators who are attempting to save a family from a powerful demonic spirit attached to their home. The plot stands on its own, and the movie doesn’t rely on the scariness to keep it interesting. Although its terror is by no means diminished; “The Conjuring” is a typical horror movie with a few twists that are done very well. It is a worthwhile watch for anyone seeking to be both entertained and terrified.

“Funny Games” (2007)

Horror films usually come in the shape of a triangle. There is a villain, a victim and us, the passive audience. The triangle is quite simple: the villain torments the victim, and through a thorny psychological mechanism, we are happily entertained. But what if someone — say Michael Haneke in “Funny Games” — decided to turn the triangle into a line? That is, what if the villain could pass by the victim to torment us instead? What if in place of entertainment we were to receive the punishment traditionally reserved for fictional victims? Haneke’s “Funny Games” not only asks these questions but answers them for you — or, shall I say, in spite of you. The film is a flat-out war against the audience, a confrontation taken to its ultimate consequences. The reason, presumably, is to make us conscious about the problematic nature of our entertainment. It brings to the fore the degree to which we enjoy and are amused by sheer, often pointless, violence. In an interview with The New York Times, Haneke argues that his film tries “to rape the viewer into independence,” and to what extent he achieves the former, but not the latter, is for each person to discover.

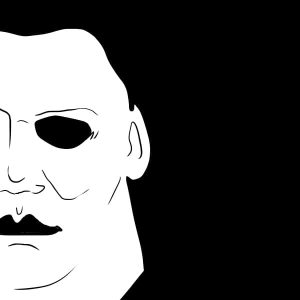

“Halloween” (1978)

“Halloween,” “Halloween II,” “Halloween III,” “Halloween 4,” “Halloween 5,” “Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers,” “Halloween H20,” “Halloween: Resurrection” and Rob Zombie’s remake of “Halloween.” You think those are enough sequels that have the same damn villain (with the exception of “Halloween III”)? Despite its notorious and terrible sequel run, the original remains a landmark in cinematic history. The film strays away from the gore and blood that was so common in the contemporaneous films like “Dracula” and “Night of the Living Dead,” and marked a new era in how we define horror movies. When Bob gets hanged on the wall by Myers’ knife, Myers simply stands there in silence, observing Bob’s final limp motions like a curious child. No blood. No gore. Just brilliance.