Author: Scott Weisman

Rating: 3.0/5.0

Vladimir Nabokov once said that there was only one school in literature — that of talent. This can be extended to other fields of art, and artists with talent are always to some degree enchanters; their work makes everything feel both petty and sublime. Scott Weisman’s “Great Gray Towers” — a collection of articles chronicling the history of Graffiti Hall — makes it (perhaps unintentionally) clear that the artists were not especially talented, or if they were, they were too self-absorbed to create really good art. The theme threading the articles is almost constant: The oppressive administration is trying to silence a lone group of young, brazenly individualistic, rebellious artists. However, the romanticism of this theme seems too overdone to be believable, and it eventually gives way to readerly irritation.

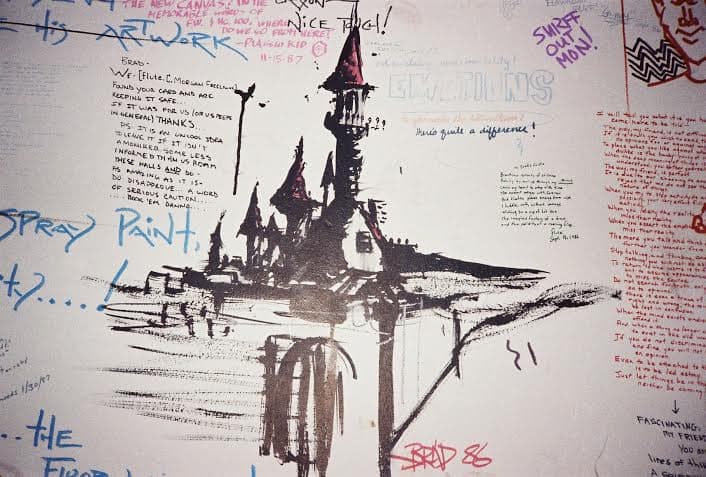

It’s hard to imagine that most of the “art” and “poetry” the book showcases was once really “one of the few things that brings spirit, art and beauty to this campus,” as one wall-writer puts it in a cited Letter to the Editor. While the case can be made that Weisman never directly expresses this, many of the articles he uses implicitly hold to this viewpoint, which is romantic to a fault. Certainly no one will shed any tears about the loss of this overwrought poem found on one wall: “In hour of night, by Hecate’s light/ When stout-hearted men stay home in fright/ We come, and oft with voices low/ Dare travel where we ought not go …” In general, much of the art seems to center around ideas like existentialism, rebellion against authority and self-expression. Occasionally, artwork that appears to be “just for fun” is presented, and these by far are the most enjoyable and least self-important.

But masterful poetry and art was apparently never the draw to Graffiti Hall; the most frequently cited reason for its popularity was its ability to connect people and offer them a way to express their feelings. On the walls were various statements which reflected a newfound sensitivity to the world and an increased awareness of the society’s unjust structures. It’s tempting to call this what it most obviously is (late adolescence), but it’s also clear that among the eight “families” who made the walls their home, there really was a magic — a feeling of camaraderie and defiance — in what they created. With this in mind, it’s easier to feel a glimmer of sympathy for the artists, even if they seem pretentious. This turns out to be the book’s saving grace — the aspect that, for all the repetitiveness and angst, makes it more like a tragedy than a farce.

Weisman has done a commendable job gathering what must be all the articles ever published about Graffiti Hall. The question remains, however, whether it was worth it. As the years go on, the answer seems more likely to be “no.” The art in Graffiti Hall was made by a few people mostly as a way to sublimate their stresses and joys, and its appeal seems to have ended with “self-expression,” excluding anything more mature and long-lasting. New classes of UCSD students will enroll and graduate, both unaware of and increasingly apathetic toward the blank walls’ silent pathos. Weisman’s book ends with a sense of history made and lost, but the history, like much of the art, held the most enchantment for its creators.