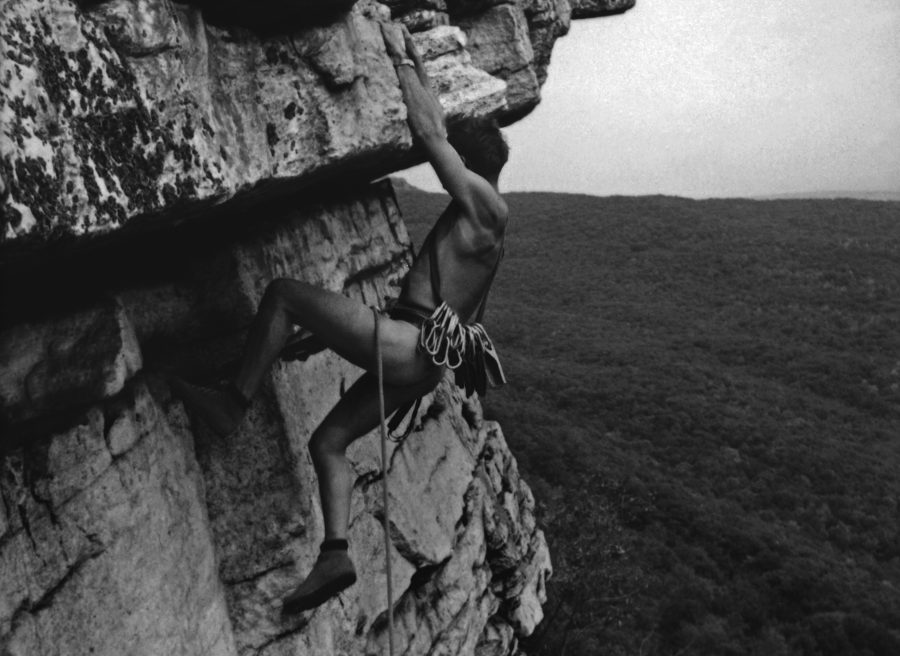

“It’s really hard to explain why anyone would risk their life to climb up a rock for no reason. It’s not like you’re finding the Holy Grail at the top, and it’s not like you can’t get to the top any other way … It’s not a tangible thing you can explain. And it’s really hard to describe why you would do that, when you are in fact risking your life.” That’s how Oakley Anderson-Moore, director of “Brave New Wild,” describes the compulsion at the heart of her new documentary.

What drives rock climbers to do what they do is a compelling question, especially given rock climbing’s recent surge in popularity, with indoor climbing gyms popping up all over the place. Yet it’s a question which has received little attention, despite the existence of an entire subgenre of rock-climbing movies. Like other “extreme sport” films though, these primarily consist of supercuts of great moments in the sport, with minimal inquisitiveness as to what drives climbers. As Anderson-Moore calls it, they’re “climbing porn” for those already within the subculture.

Drawing upon historical footage, occasionally supplemented with animation, “Brave New Wild” attempts to answer this urge, primarily by chronicling the golden age of climbing in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“[Climbing] is not as small as it once was. One reason I wanted to make this film was just to make sure that the history of this sport didn’t get lost in this growth,” Anderson-Moore said.

At the center of this narrative stands Warren Harding and Royal Robbins, two legendary climbers competing to be the master of their age. A filmmaker could not ask for a better duo at the center of her story. Robbins and Harding, despite their common obsession, contrast as strongly as Apollo and Dionysus. Robbins is poetic, controlled and poised, believing in the purity and ethics of the climb. Harding is gruff and passionate, as interested in drinking as he is in climbing. In his own words, Robbins saw climbing as a way of “getting rid of fear.” For Harding, climbing was just a “silly, asshole-ish thing to do” — just a way to have fun and indulge the ego.

Both of these views constitute an escape from the dominant culture of the day. As much as “Brave New Wild” chronicles the golden age of climbing, it refrains from becoming too obsessed with a single thesis and turning the film into a pedantic lecture. Rather it indulges in the fact that, as Anderson-Moore says, “climbing is basically the vehicle through which we’re talking about these different things: about what’s important in your life and what the whole point is of doing anything. Climbing is a small thing that people do but leads to all these big questions.”

Rock climbing, both as a sport and as a lifestyle, is inseparable from the culture it was born in — a consequence of the post-war conformity and economic expansion of the 1950s that eventually spawned the hippie movement. “Brave New Wild” walks an offbeat and circuitous path, telling the stories of those who witnessed this age and the curious adventures they experienced.

Central to this is Anderson-Moore’s own father, Mark Moore, who dropped out of society following the Kennedy assassination in 1963 and became a climber of some renown. While Harding and Robbins’ continue their famous fight to ascend the “Dawn Wall” in Yosemite, the film interweaves Mark Moore’s own experiences into the narrative, roaming through the personal moments that were an accepted part of the dirtbag lifestyle: hopping trains, working odd-jobs and avoiding the authorities.

According to Anderson-Moore, documentarian Errol Morris’ films, such as “Fast, Cheap & Out of Control,” played a huge part in the structure of her own documentary.

“Morris takes a bunch of different, unrelated things … and makes a film where he pieces things together thematically … You can still draw great meaning from connecting completely unrelated people and things that relate to each other thematically. And that could give the audience room to think about the connections on their own,” she said.

Like the documentarians she admires, Anderson-Moore isn’t afraid to put herself, for brief moments, into the film. Anderson-Moore graduated from UCSD in 2007 with a double major in visual arts and in theater arts. Like many students on graduation day, she found herself unsure of where to take her talents and interests.

“I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do, and who am I as a person, and what my life is going to be. So I started looking at the life of my dad — I think I was the same age my father was when he started getting into climbing,” she said. Six years later, “Brave New Wild” was released.

Does it arrive at a satisfactory reason for why people go out and climb? Perhaps. For Anderson-Moore, climbing “is cool because we live in this world where safety and security is the number one priority in our culture. Which is understandable. But … you can’t just be scared all the time, trying to stay safe, and live as long as you can in the comfort of your own home, because then you’re not really living. Climbing is a great way to go out and confront your fears; it can be very valuable to know who you are.”

But “Brave New Wild” delves past such easy conclusions, recognizing that truth is not so easily distilled and may require years of wandering. Indeed, as one climber in the film says: “If you have to ask why, you wouldn’t understand even if the reason were explained.”