In this article, News Editor Jacob Sutherland discusses the need for individuals to demand both identity representation and tangible policy measures from their political candidates.

Around the summer of 2019, I remember seeing various tweets which followed the logic of: “If you don’t support Mayor Pete in this election then you’re not a good gay.” I was very much taken aback by this. At the time, the South Bend mayor had not even put out a concrete plan to accomplish any major policy goals, let alone to address problems within the LGBTQ community.

Despite this, there was a vocal portion of the gay population who disregarded Senator Bernie Sanders’ 50-plus years of supporting the queer community and Senator Elizabeth Warren’s plans to address issues within the community in favor of an inexperienced politician whose only redeeming feature at the time was his sexual orientation. This was done essentially in blatant disregard for tangible progress in favor of symbolic representation.

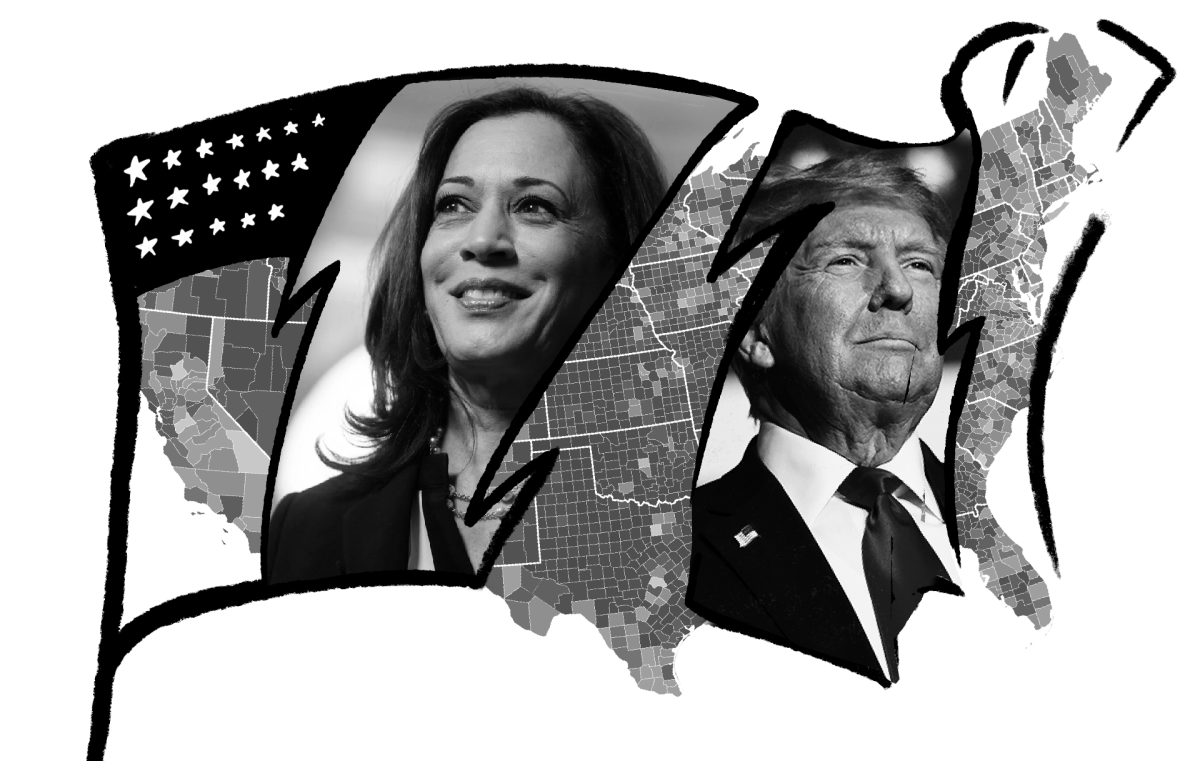

Identity politics fuels the ambitions of many candidates, ranging from the lowest stakes elections like Associated Students, all the way up to the presidency. And by some metrics, this is not a bad thing. The United States’ foundation is rooted in the exclusion of minorities from the political world, especially for women and people of color. Seeing headlines like “A record number of women are running for the House this year” inspires those who have been traditionally left out of politics.

However, the danger of identity politics comes when policy proposals, or in some cases a lack thereof, are overlooked in favor of one’s personal background. Seeing an openly queer person running as the Democratic nominee for president would have been such an inspiring thing to see as a gay person. But the reason I personally did not vote for the only openly gay candidate during the primary was because other candidates had policy proposals that would help the queer community a million times more than simply having a queer figurehead with no substantial policy goals in office.

We have to find a balance between identity and policy if we are going to move forward into an era of maintaining a truly representative democracy. A common argument from those who discount the value of representation in its entirety follows: “white men are just better at politics because they have more experience.” This of course is nonsense, but is still an argument we must push past to achieve a healthy balance of identity and policy.

UC Santa Barbara social psychologist Brenda Major’s research suggests that the best way to have someone overcome their insecurities with running for office is to go ahead and ask them to run. While Major’s work predominantly focuses on women, this principle can be applied to anyone — one of the greatest barriers to running is simply feeling that you are not confident in your own capabilities.

If we want to see a healthy balance of identity and policy, we must actively seek out those who share both our identities and our policy priorities and ask them to run. This may not be as practical for nationwide races like the presidency. That said, we all likely know someone personally who shares these characteristics and would be an amazing addition to A.S. Council, the local city council, or even the state legislature. And with a little introspection, whose to say we can’t ask ourselves to run and advocate for the policies we believe in while providing the representation we long for?

I encourage you all to approach politics through this lens of balance. We certainly can have our cake and eat it too, but we must be the ones to go visit the bakery and select a cake which meets all of our intersecting priorities in the first place.

Art by UCSD Guardian artist Kyoko Downey.