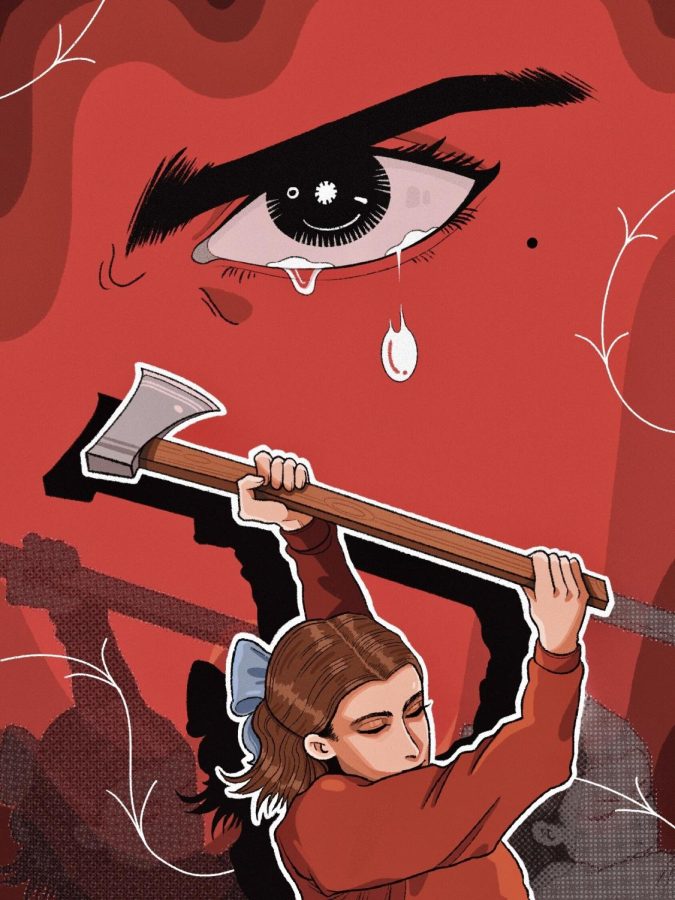

The Marketable Female Rage

May 21, 2023

There is a crossing of both suffering and anger in response to pain but also a connection between women displaying the expression in the “right” way and one that is inappropriate.

Smile more. Not too much. Just enough. Occasionally, my mother would tell me that people might not want to converse with me if I don’t smile — a natural-looking one with teeth. A specific smile. However, as kindly as a light “smile more” seems on the surface, it is true that many women use the hospitable expression as a tool of pacification rather than genuine joy. Whereas pain requires a reason to manifest, a smile that represents contentment can be more commonplace: a simple formality and a consoling sight for oneself and others. It, like socially appropriate anguish, is befitting of a woman.

There is a gravitation to female suffering. Dorothea Lange’s universally-known photo of the “Migrant Woman” is representative of the Great Depression pains, especially for women — a time fraught with little money, food scarcity, and husbands (often the breadwinners of the family) who very well could leave their wives and children. The woman in the photograph with the furrowed eyebrows has two children nestled into her — she is akin to a suffering Madonna in the flesh.

Let us consider artist Fiona Apple. Her tunes go all the way back to the 90s and have found themselves in many short TikTok songs — until her discography vanished from TikTok in August of 2022. One fan surmised in a very popular tweet that Fiona Apple saw that it was because “people on TikTok were appropriating her music for their shallow, reductive aesthetics that do nothing but fetishize female pain.” Indeed, Apple’s lyrics, which are often somber, have put her in a category where her suffering can mean good music, which is not too far off from other artists’ experiences with their fans when producing songs.

Others responded to the tweet with how individuals could identify with music in any way they wished to, especially the youth that are learning how to manage their emotions. There is no denying: this overlap between displaying the suffering one feels and being the subject of scrutiny for showing it or “too much.” There is a “correct” kind of display of pain if one does display it.

Anger, though, is more intense and not as easy to sympathize with as grief or sadness. Anger is different because if it leads to rash actions, there are societal norms intact to keep the person accountable or ashamed. Still, the expression of anger still can feel like a righteous crown to wear — red-hot on the exterior but warm atop one’s head.

Individuals exhibit less sympathy when such expressions of anger are loud and performative or seemingly entitled, which is why the unruly men and women dubbed Kens and Karens today receive so much flack.The anger, too, needs to be right. And for anger, in particular, this makes sense. For it to lead to better consequences, anger has to be productive. But for women, in particular, showcasing anger isn’t befitting. She is the “crazy, hysterical woman” or when it gets more specific, the “angry, Black woman.”

But author Dr. Pragya Agarwal of “Hysterical: Exploding the Myth of Gendered Emotions” states that there isn’t a different female and male brain when angry — women are just more likely to have grown up bottling it up through gendered socialization and learning that expressing it wasn’t womanly just as men crying is unmanly. Showing tears and emotion, however, is.

In a BBC interview to promote “The Menu,” actress Anya Taylor-Joy rejects the sentimental trope of a woman staying quiet when she is wronged. In the movie, Taylor-Joy’s character lunges for her date at the dinner table after she discovers he threatened her livelihood. She says that women do get angry. There is no singular tear rolling down their cheek after they are intensely wronged, contrary to what some believe or want to believe. They are not as hurt as they are angry.

In “Pearl,” too, the main character Pearl is evidently unstable and potentially sociopathic but she too succumbs to her anger in violent, outward ways for reasons that are relatable to the average Joe. In the movie, she needs to care for her infirm father under the watchful eye of her restrictive mother as well as combat feeling stifled and bitter while waiting for her husband to return from war. She doesn’t wish to raise children and doesn’t relish tending to her homestead; her anger stems from wishing to rise above the status quo and simply being unable to.

Ultimately, in the loss of love — both familial and romantic — she wields a bloody ax against anyone in her wake as she confirms that “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” But Pearl is not apathetic to her malicious actions. She often sobs and despairs at her malicious actions, all of which stemmed from an immediate reaction to potentially losing someone or a chance at something opportune for herself.

She is akin to the old tales of maternal figures like La Llorona who have to wander the waters, mourning the children she drowned — the consequences. But she also echoes Greek stories and old tales of women bitter with rage that get revenge — such as Medea with Jason when she learns of his unfaithfulness.

These women are the antiheroes, the ones who waste no time letting their feelings fester. Whereas women are statistically often the victims or at least the observers of male violence in action movies, they take the lead as something else in the recent movies. Beyond the screen, commenters of videos on “Pearl” stated that they understood her feelings of abandonment and feeling dismissed by family.

Even then, these movies — often thriller or horror — depict women in mediums where they can be angry. It’s entertaining; it’s fake by the time the curtains close. And though these characters may survive the movie, they live with the knowledge that they haven’t circumvented the consequences of their anger — justified or not. They are still alone or on the fringes of society; their anger helps them survive, but it’s not necessarily productive.

Professor in film studies at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Lisa Coutlhard tells BBC Culture that women’s anger in the media usually is a response to the loss of love or the loss of a child such as in the cult classic “Kill Bill,” when Uma Thurman’s character “The Bride” only goes on a killing spree after her loved ones and unborn child are killed by her lover. Even in “Pearl,” a fight between Pearl and her mother becomes violent after they both battle their internal dissatisfaction occupying different roles as wife and caretaker.

“[Characters’] violent vengeance is deemed appropriate or acceptable because of the level of violence that precipitated their actions,” Coulthard says to BBC Culture.

Thus, there is a maternal kind of rage in responding to a genuinely valid feeling such as rejection or unjust killing — though rash.

But such extends to reality as well. Female serial killers are rare, but when they do kill, the rationale is often more personal — such as due to money or sexual assault— than male serial killers. And on screen, these ultimately draw sympathy from the audience because they are not solely out to be violent criminals but to fight tooth and nail for something they’ve lost or may lose. In other words, they are multidimensional and not cookie-cutter teary or jovial.

Following the COVID pandemic, too, many women expressed their anger at not only making money but taking care of family even more in a confined space and feeling shame when they felt irritability with their loved ones.

In a paper from the National Library of Medicine on living during COVID, the authors detailed an increase in depressive and anxiety disorders in women during lockdown and gendered differences (like women being associated with anxiety and men being associated with aggression)decreasing with children in their households, such as men becoming more anxious.

But in the paper, whereas anxiety and mood disorders are more commonplace in women than men, externalizing aggression and substance abuse disorders are more commonly found in men than women. Similarly, in the study, “The Girl Who Cried Pain,” from 2001, the researchers noted that women sought more coping strategies such as avoidance or seeking social support whereas men were more stoic and engaged in exercise or accepting the situation.

While it may be more difficult to sympathize with anger—or understand it, even female pain is often dismissed. Women crying and releasing the video to the public is perceived as a call for action — or a desire for attention. Again, when vulnerable feelings coincide with aspects such as performance, they seem less authentic.

The study further implies that women are more likely to be seen as making up their pains and that their pains are more emotionally-oriented than men’s. There is a fear of being known as an attention-seeker, of being tied to one’s pains like it’s part of their identity.

Still, anger is more threatening.

“It’s expected for a woman to be sad and emotional. When a woman is angry, suddenly, she’s not chill,” Sanika Walimbe, a Eleanor Roosevelt College senior, said.

Walimbe further adds that she notes an infatuation in comment sections of individuals with “B.P.D” (or borderline-personality disorder) women, until the individuals see the aspects of it that make the mental illness so difficult to endure such as outbursts and impulsivity.

In other words, there is a tricky balance between recognizing rage or pain and exalting it. When one dismisses it, there is a longing to see the “right” kind of pain in women. But when one romanticizes it, there isn’t productivity there either.

Author Leslie Jamison asks in a 2014 essay, “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” how we represent female pain “without producing a culture in which this pain has been fetishized to the point of fantasy or imperative.” She states that rejecting the wounded woman image is just as reductive as relying too much on it.

Though we’re attracted to and repulsed by female pain, the possibility of reifying it shouldn’t stop us from recognizing it. To her, an individual needing attention is still quite valid as it’s a human need.

And there is a way for the anger to be productive. In media surrounding female rage, the titular women address their anger head-on. To suppress it would only exacerbate it and lead to higher cortisol levels. There is catharsis in not following the women’s rash decisions but embracing how anger isn’t often contained. And perhaps as long as it’s respectful, it doesn’t have to be.

There are rage rooms — a growing amount of them — that allow an individual to turn their internal anger outwards into smashing things against the walls and floors. There are the female-associated strategies that do work for many women — such as turning to health care and engaging in positive self-talk. To others, it’s political organizations and writing to combat the rage that comes from patriarchal harm — the one that used to almost always make women as the victims in action or horror movies or certain types of women the only survivor.

At the end of the film, Pearl smiles at us — a pained smile she practices throughout the film for her role as a troupe dancer and performer in general. She is confined not just to her homestead again but to the gender norms for her as well. The default emotion here is not flatness or discontentment at the loss of her freedom. It is, preferably, a smile: one that greets, one that serves, one that pretends. Smile more. It is a tool of containment, after all.

Art Courtesy of Michelle Deng

Laverna Lehner • Oct 9, 2023 at 8:45 pm

I’ve been reading your post for the past several days and have found it to be quite helpful.