This past month the Supreme Court had a leak of a decision, which decisively overturned Roe v. Wade (1973) and the less well known Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). Shortly after the Roe overturning was leaked, there was a lot of speculation on social media about a part of the decision concerning a series of past LGBTQ rights decisions. These decisions were mentioned because they relied on the implicit implications of the 14th amendment just like Roe does. The Court states on page 32 of the leaked opinion called Dobbs v. Jackson, “None of these rights have any claim to being deeply rooted in history.” What seems to be implied here is that not only is Roe being overturned but so is everything related to it.

So the question raised here is: Is the Court overturning not just Roe but dozens of decisions from the past 50 years? Analysis of the Court and the leaked opinions leads me to argue that the Court might overturn Roe and Casey, but for now the Court will keep the other rights based on privacy. This is because the Court states in the leaked opinion that the rights enshrined by Roe and Casey are different from the rights enshrined by the other cases. What’s most concerning about this leaked decision is not the aforementioned paragraph but the disregard for Court precedent, which in the future might endanger already protected LGBTQ rights. However, even if the Court really wanted to overturn everything based on Roe and leave it up to the states, doing so would probably result in a fiery congressional amendment neutering the Supreme Court.

The argument that Roe makes is concerning the idea of a citizen’s right to liberty in the 14th Amendment. In Roe, the majority argues that a person’s right to an abortion is part of their liberty promised to her by the 14th amendment. The majority Court opinion in this case argues that a birthing person has this liberty and a fetus does not. Roe argues that, despite the philosophical debate about when life begins, the law does not treat a fetus like a person and therefore a fetus does not have the right to life and liberty that a birthing person does. This is the person’s right to privacy. This is a reasonable opinion following the precedent of similar 14th amendment privacy cases, but considering its loose interpretation, it was likely to be overturned by conservative judges.

Following Roe was Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). This decision was interesting because despite the fact that the conservative judges didn’t agree with the reasoning in Roe, they still upheld it. The reason for this was the idea of stare decisis, which means that even if they think it’s poorly justified, it’s the law and they respect the precedent. This is usually the policy for conservative judges — which are notably different from conservative politicians. Conservative judges are constitutional originalists, which means they believe that the constitution should only be interpreted strictly and generally they adhere strongly to past decisions, even non-originalist precedent. Their idea is to interpret the law strictly and keep things grounded. What’s significant about this decision was that it reaffirmed Roe and set a strong precedent that would be harder to overturn. It set a groundwork for further privacy cases such as Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which enshrined the right to be gay without government interference, and the famous Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) which enshired the right to gay marriage under the argument of privacy. Casey set solid precedent for cases central to LGBTQ rights.

The leaked Roe decision, which is called Dobbs v. Jackson (2022), overturns both Roe and Casey. The opinion here is messy, but there are a few ideas that seem central. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the opinion, takes the position that a woman’s liberty exists but maybe the fetus’ liberty actually exists too. The Court doesn’t take a stance on if a fetus is a person or not, but rather takes a states’ rights approach to saying that if you believe that a fetus is a person you have the right in your state to regulate abortion (33). This states’ rights approach is a popular conservative view, and conservative courts will usually take from the federal government’s power and give back the states. Regarding the privacy argument, Alito says, “What sharply distinguishes the right to abortion from the rights recognized in the cases on which Roe and Casey rely is something that both those decisions acknowledged: Abortion destroys what those decisions call “potential life” and what the law at issue in this case regards as the life of an ‘unborn human being’” (32). Alito is saying here that Roe is different because theoretically the life of the fetus is endangered, which isn’t the case in cases giving rights to gay people or to interracial couples. In this paragraph, it seems Alito is implying that the right to privacy for these groups is protected and that the only exceptions to the rule are Roe and Casey. This leads me to believe that although overturning Roe and Casey, the Court is not overturning anything but Roe and Casey. Alito’s logic isn’t necessarily coherent, but the Court makes a point to highlight the preservation of LGBTQ rights and other privacy based civil rights cases, demonstrating the Court’s awareness of the importance of these rights. Even if it’s not originalist, the Court is keeping these rights for now. This is good news for LGBTQ activists and signals a positive shift in the Court.

Although, an important question raised by this argument is, “What about stare decisis? If this Court is so conservative shouldn’t they follow their own rules and not make radical changes to precedent?” Alito addresses this argument by saying that the Roe argument and Casey arguments are so terrible that stare decisis just doesn’t count. More professionally, Alito argues that the Roe and Casey decisions do not meet the requirements for stare decisis to apply (62). This is the concerning part of this decision. Although Alito builds an argument for his disregard, it marks a change in the thinking of conservative judges and a move towards a more activist conservative courtship. This precedent is dangerous for those who care about LGBTQ rights, as now conservative courts have shifted to be more willing to overturn decisions which they previously would have held following stare decisis. This is a real concern, especially concerning conservative justices’ distaste for the legal basis of past LGBTQ decisions and LGBTQ decisions on the more modern side, as seen in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), where the Court almost ruled against transgender rights but didn’t because of Gorsuch’s view of the particular document in question. Future cases or past cases might not be so lucky as Bostock.

To ease anxiety, I would argue that an activist Court will not go around overturning every civil rights decision of the past century. The Supreme Court is limited, and decisions such as gay marriage and interracial marriage have entered the the realm of enormous support. According to a Gallup poll, 70% of Americans support gay marriage. A decision to overturn gay marriage would illicit a response from Congress, the Supreme Court’s check. This would lead to an Amendment changing the power of the Supreme Court, possibly stripping all its power. This is the Supreme Court’s worst nightmare and is probably the reason that Alito drew a line between Roe and Obergefell. Even if the conservative judges want to take every right we have away, they care more about their own self-preservation of power.

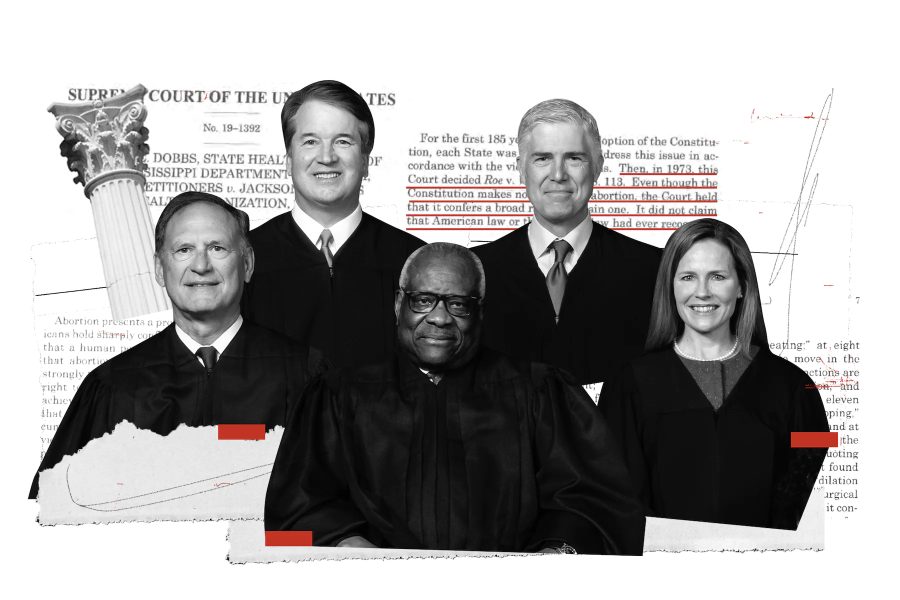

Image courtesy of Fred Schilling for The Washington Post.

gregory scott garner • Jun 24, 2022 at 8:13 am

Lots of annulments coming up for Sweetie…Gee, I wonder if all those decent Christian bakers and florists will be able to countersue???? I hope they show the same mercy that was demonstrated towards THEM…