There is a decent pool of Americans who will insist they do not have an accent. Of course, there are accents that are found within Southern regions of America or on the East Coast, but still, some Americans may describe their way of speaking to not have a specific “flair” — it’s just “normal.” “Accentless” Americans do, contrary to their belief, have an accent. The reason they might have never realized it is because it does not inconvenience them.

The denial of otherwise available goods or services by phone is what has been coined “linguistic profiling,” and it is the auditory correspondent to racial profiling, which relies on visual cues. Over the phone, employers or landlords, for sake of example, can utilize accents of potential job applicants or tenants to decide whether or not they want to turn them away.

It is not linguistic profiling for someone to acknowledge a caller sounds Latino, Black, Indian, or any other racial or ethnic background. It becomes linguistic profiling once someone attaches their implicit biases to the fact that callers sound as if they are part of a certain group or community and decides to discriminate against them. It is an easy way for people to quickly make assumptions about a caller and decide if they are part of a community they have a prejudice against. While turning away a caller on the phone may sound mundane, linguistic profiling is another way for those with implicit biases against people of color to potentially put minorities in disadvantaged situations. What is exceptionally upsetting, is that people will linguistically profile communities for the way they sound, but will still actively use ways of speech (such as terms or vernacular) used by POC once it is trending.

Within America, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Fair Housing Act of 1968 both account for linguistic profiling and the Civil Rights Act has avowed discrimination based on “linguistic characteristics of a national origin group” are forbidden. While these laws were a step in the right direction, linguistic profiling has proven difficult to fight within the court of law; especially as it can be challenging to document speech was the basis for discrimination. Does that mean it is not happening? No. It means someone can discriminate against someone else on the basis of an accent they hold as distasteful and potentially get off with no consequence. Lack of consequence allows for people to not be held accountable for when they do discriminate on the basis of linguistic profiling. That means not only are victims left without justice, but perpetrators are left without seeing reason to change their mentality nor behavior.

Lack of consequence can also perpetuate the notion that linguistic profiling does affect anyone. Studies that have focused on linguistic profiling have been able to find a correlation between accents used and whether or not individuals get a call back. The correlation does not give the full picture, but it does encourage further research and investigation.

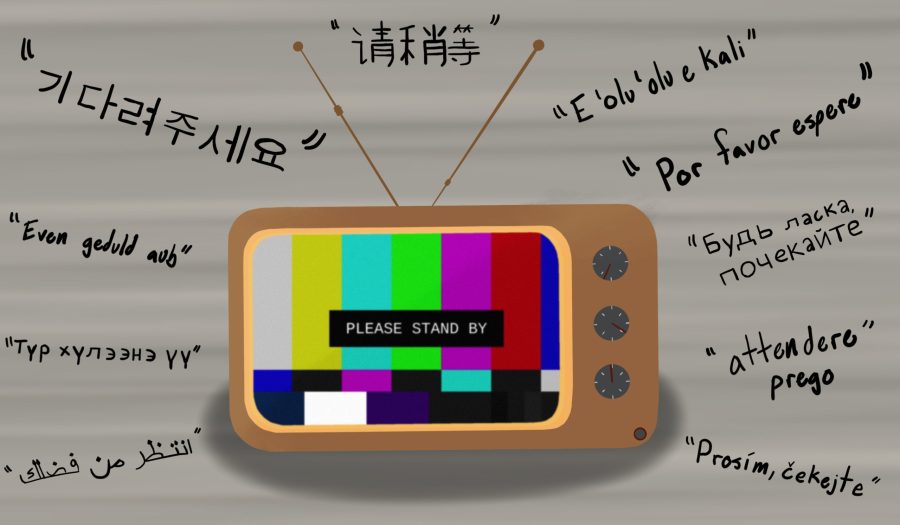

Current data on linguistic profiling remains conservative, as not many cases can be represented and few may admit to actively doing it. But in reality, linguistic profiling does happen, and all while someone can disadvantage POC for the way they speak, they can be using popularized POC terms. African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), Mexican Slang, Japanese words, and plenty of other culture’s speech have been highlighted by trends, allowing for anyone to suddenly be taking pieces of that culture’s vernacular and incorporate it into their own verbal communication. “Accentless” Americans have found themselves within a group who enjoys playing with words and phrases like “woke,” “por favor,” or even ”sugoi.” It might make you feel quirky and it might feel harmless. In reality, it is tone deaf. POC, as humans, can be turned away, but their culture and way of speaking can be accepted because it’s “fun.”

Using POC terms while linguistically profiling them only supports the notion that minorities are accepted in capacities that are convenient for others. The issue is not entirely about accents or the way someone speaks, it’s about trying to distance yourself from who has the accent.

To reduce someone down to an unappealing voice and then turn around and try to speak in manners specific to their culture is a display of your privilege. But again, the issue does not solely lie within accents — it’s an issue with acting on implicit biases. That’s what disadvantages people. The fear and overgeneralizations of POC plays into why there are many disparities within the healthcare system, within the housing market, and within the education system.

Implicit bias is defined as attitudes towards people or associated stereotypes with them without our conscious knowledge. Some psychologists say even those aware of implicit biases do not really see behavioral changes, as they are not in an environment where they would unlearn their assumptions about others. However, turning away POC over the phone to distance yourself from them is not going to put you in an environment where you reconstruct your generalizations about minorities.

For many college students, moving to their universities tends to be a cultural shock, as it is the first instance where individuals are exposed to students who have varying identities to their own. These instances put students in situations where they are seeing more POC than they may have previously, and that is vital to getting people to recognize that these populations are not too different from them. Exposure doesn’t solve the problem, but it does create a space where individuals have to think about their perception of POC. Better understanding POC needs to be an active effort, one where you are willing to relearn what you may have thought to know about them. You cannot just try to avoid encounters with them, mimic their vernacular, and hope that something changes within yourself.

Art by Ava Bayley for the UC San Diego Guardian.

Elisabeth • Mar 25, 2021 at 10:54 am

You can have the most beautiful, easiest-to-use website in the world, continue reading about web design and development, but if no one can find it, then what was the effort to create it for?