Despite the prevalence of sickness on campus, UC San Diego does not enforce a school-wide sickness policy. Yet, UCSD clearly does not intend to take responsibility for its role in spreading sickness across campus. Instead, professors have full discretion over whether or not students can miss class when they are sick. Some of the common attendance policies professors put in place include requiring attendance for a majority of lectures and lowering grades when people miss more than a certain number, only allowing students to miss class without a penalty if they provide a doctor’s note or not allowing students to miss any class even with one. While requiring attendance no matter what is harsh, missing one or two classes usually does not greatly affect one’s grade in the class overall, especially if the student still has access to podcasts or other class materials. Unfortunately, many of the lectures here are not podcasted and students usually have no direct way to access missed material, which could affect their exam and paper grades. The policy for missing exams is even more strict likely because exams are worth a high percentage of students’ grades, and a doctor’s note is usually required by professors in order to miss an exam or justify a paper extension. The lack of consistency in these policies, as well as the overall inability of many to actually adhere to these policies, cause students to come to class sneezing, coughing, and spreading pathogens to other students, who in turn are subject to the same unfair policies. If UCSD enforced a fair policy that allows students to recover from sickness instead of coming to school sick, situations like this could be easily avoided.

These inflexible sickness policies threaten the health of all San Diegans as well as the family and friends of UCSD students and employees. The fact that many professors’ policies require and encourage sick students to attend class means that healthy students, people connected with professors, students, and campus employees are exposed to illnesses present on campus. This exposure could have serious implications for people most vulnerable to the common cold and flu, for example children, seniors, and people who have weakened immune systems. These populations are more likely to develop pneumonia after having a cold, especially the flu, and experience complications ranging from six to eight weeks of missed work or school to death. Death and severe complications from common colds and flus are not normal even for vulnerable populations. However, the possibility of these complications increases when a great number of people are exposed to illnesses that trigger them. Yet, professors are allowed to actively encourage the attendance of sick students, which increases the chance that others will acquire and suffer from highly contagious illnesses. Such policies, especially in the context of severe flu seasons, are alarming. Worse yet, these inflexible policies stand against the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — quite questionable for a school promoting itself as a hub for medical progress. Overall, while death, severe complications, and general harm to society are not the direct result or intent of any one professor’s inflexible sickness policy, that does not alter their impact.

Professors’ high level of discretion over their class attendance and sickness policies often makes missing classes and exams without repercussions difficult for sick students. Unfortunately, these policies hit working students, who hold paid jobs to supplement their education, the hardest. Due to financial obligations, working students typically cannot, or feel they cannot, call out of work to rest. When professors have policies that penalize students for recovering, working students are then also coerced into attending class instead of resting. Inevitably, this means working students are unable to get the rest they need to avoid being sicker for a longer period of time than they would be otherwise. As a result of extended sickness students face reduced academic and work performance for a longer period of time and increased risk of developing poorer health in the long term. Additionally, between the stressors of student life and financial obligations, working students may not have the time or financial ability to get a doctor’s note excusing them from more important school obligations like labs, quizzes, midterms, and other tests. Thus, despite evidence that common colds and the flu impair cognitive performance and memory, professors’ inflexible policies generally force sick working students to sit through tests anyways. Reduced performance on such assignments can have disastrous impacts on students’ grades and thus future opportunities. That being said, the exact impact of sickness on students’ grades remains elusive. Regardless, it is easy to see how inflexible sickness policies further harm working students’ ability to succeed and remain healthy at UCSD.

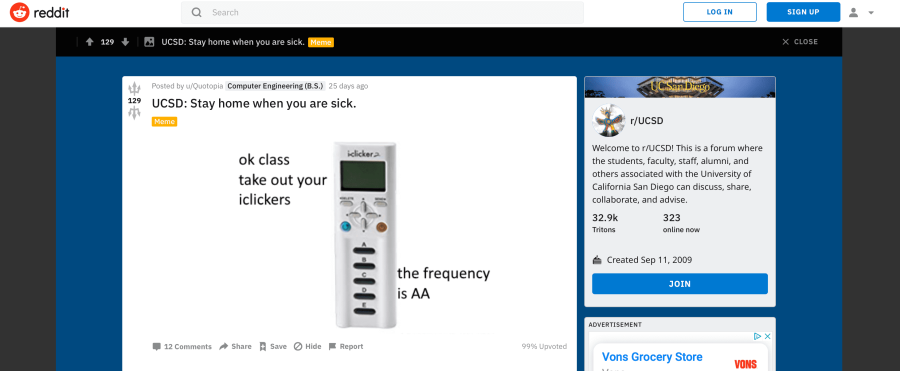

Furthermore, these policies cause students to feel that UCSD and its professors especially do not care about students’ health, well-being, and overall success. Students at UCSD express their disillusionment about UCSD’s failure to address their needs on Reddit boards, Facebook, and in day-to-day conversations. Regardless of the truth of these accusations, professor policies that refuse to realistically address student sickness fuel this sentiment among the student body. And this talk produces effects; when students feel the university does not care about them, the university, current students, and future students suffer. Studies of presenteeism — when workers are forced to attend work sick — link inflexible sickness policies to decreased desire to give back to the workplace, higher turnover, and general feelings of negativity toward the workplace. Though UCSD is not a business, student sickness policies that refuse to support individuals have the same effects on our campus. On a tangible level, these policies are just another part of the system at UCSD that keeps students from wanting to spend their time in service to the university. Additionally, alumni who felt unvalued at UCSD due to policies like professors’ sickness policies are unlikely to invest their time and money into the school in the future. Finally, students’ relationships with their professors, who are meant to teach and mentor students, suffer.

With all of the issues imposed by these unrealistic policies, there are steps that the university must take to alleviate the aforementioned issues. Instead of forcing students to abide by unrealistic policies, UCSD should have a general school-wide policy that all professors must use. These policies should allow students to take care of themselves when sick without requiring them to get a doctor’s note when all they need is some actual rest. Students should be allowed a certain, set number of “sick days” without any grade penalty. If students are missing more than that set amount, only then should they be required to bring a doctor’s note. For exams, projects, and papers, professors should be required to accept a doctor’s note and provide a make-up exam or adequate extensions. This school-wide policy would reduce the number of students who go to class sick, decreasing the spread of disease and ultimately creating fewer issues at present. Professors who continue to use their own policies, especially ones that do not allow students to recover from sickness, should be reprimanded to help enforce this policy. Even if different types of classes require different levels of attendance, UCSD could still enforce a more broad, overarching policy and departments could create fair policies that accomodate lab classes, discussions, and three-hour lectures that only meet once a week. Ultimately, the policy should not be as proactive in assuming that students will be dishonest and miss class, but instead give students time to recover and only allow professors or teaching assistants to intervene on a case-by-case basis for particular students taking advantage of the policy. UCSD should care for the health and well-being of its students to actually promote practices that prevent the spread of illnesses, especially in an environment where so many people come in such close contact with each other.

While the problems posed by the lack of an overarching sickness policy seem abstract, they leave negative experiences in their wake. When I was sick with bronchitis, a professor here at UCSD refused to accept my doctors’ note. Instead, they insisted upon trying to call my doctor, despite privacy laws that restrict the release of medical information, to confirm the note’s legitimacy. My experience, while extreme, is not unique on our campus, and it would not have occurred if clear university guidelines were in place.

The university must work to enforce a broad policy and give guidelines to professors and departments regarding appropriate and realistic policies for students so that situations like mine can be avoided. If they do so UCSD will finally uphold the standards of health it has long claimed champion.

This article was cowritten by UCSD Guardian Opinion Editor Geena Roberts and UCSD Guardian Copy Editor Divya Seth.

Grace • Feb 27, 2020 at 11:44 am

You stated the graphs without giving clarity as to how the data was collected and how many students answered the question. Could you please update the article to give a better understanding and sense of clarity. Without that, the statistical significance of this finding remains vague.