For many students, Spotify’s auto-generated playlists provide the soundtracks to our lives. But does Spotify help us discover new music or simply re-introduce us to the same sounds?

Every day before I go to school, I put on my favorite “Beach Goth” playlist and get ready to songs that, to most people, probably sound the same. With vaguely obscure titles typically related to altered states of mind (e.g. “Dope on a Rope,” “Orpheus Under the Influence,” “Nicotine Dream,” “Bae Caught Me Vaping”) and a common place in the overlapping surf-rock/surf-punk/psychedelic rock sub-genres, these songs generate a veneer of SoCal edge and chill that brings me as close to chill as I will ever get. My beach goth music defines a substantial component of my selfhood, but I didn’t stumble upon those songs by chance — I found them on Spotify. Somehow, Spotify knew that I would like them before I even knew that I did.

I, like many other students at UC San Diego and young people our age, am a Spotify fiend.

Spotify is an online streaming platform that allows users to stream music and podcasts across the world. It was created in 2006 in Sweden — far from Silicon Valley, where iTunes, the definitive music application of the early 2000s, established its headquarters. Theoretically, Spotify was intended to combat the increasing problem of illegal music piracy made common by the age of YouTube and the increasing accessibility of the internet. Spotify went from being a small startup to a worldwide, multi-billion-dollar music provider that offered a desirable solution to both the listeners and the artists: listeners didn’t have to pay for songs, but the artists still received some financial compensation.

It’s almost as if the rise of Spotify eradicated any need to pirate music. Why even bother with piracy when you could just use Spotify to stream almost anything in the world for free?

Spotify’s affordable cost factor is another plus for college students. After setting up a basic account, users can stream music for free or obtain a “Premium” membership for a monthly fee, which allows the user to listen to and skip an unlimited number of songs without advertisements. This heightened song availability helps broaden users’ music tastes.

“[Spotify] allows me to discover and maintain various music tastes that heighten my senses,” John Muir College junior and electrical engineering major Emerson Noble said, explaining his appreciation for the service. “And Hulu is included with the student membership, so that’s a plus.”

According to data on Spotify’s website, members of Generation Z (those born in the mid-1990s and early 2000s) make up the platform’s primary user base. Approximately 63 percent of Gen Z uses Spotify, 67 percent use YouTube, 41 percent use radio, 29 percent use iTunes, and 20 percent use CDs. Only 35 percent of adults older than 35 years old use Spotify; most of them generally prefer more traditional methods of music consumption such as CDs or radio.

After iTunes, an Apple software exclusively for Apple devices that allowed users to purchase music and digital media, lost business due to pirating, Apple switched its business model. In 2015, the company launched its own version of Spotify called Apple Music, a streaming service that’s uniquely for Apple devices. As of June 2019, Apple Music had 50 million subscribers. Spotify had 217 million.

Read More:

Album Review: Steve Lacy’s “Apollo XXI”

The Guardian in DC: Ten Hours Waiting for the Mueller Hearing

The Apostles of Sun God

“I switched because Spotify is more personalized,” Earl Warren College senior and mathematics major Jacob Schauwecker said. He recently switched from using Apple Music. “Spotify also has much more to offer — it has podcasts, audio books, etc — whereas, based on my understanding, Apple Music doesn’t offer as much. Spotify also has a better user interface and it’s much easier to navigate Spotify’s design.”

The intense level of Spotify’s personalization is part of the appeal, especially for Generation Z. By introducing you to niche, underground bands and throwing some classics in the mix, Spotify helps you feel edgy.

Spotify knows how to make you feel special. At the end of every calendar year, Spotify releases a compilation called “Spotify Wrapped,” which is akin to a year in review of each user’s listening data. It “wraps” up your year by collecting data on your activity, such as the exact number of minutes you spent listening to music that year, your top genres, your top artists, and your top songs. It’s common for students to post screenshots of their “Spotify Wrapped” data on their Instagram and Snapchat stories. “Spotify Wrapped” neatly lists out our music — our selfhood — and captures who we are so we can share it for others to see. It’s nice to have such personalized information about what brings us pleasure. We feel understood.

“Spotify’s algorithms are pretty good,” Noble elaborated. “I don’t know exactly what they do, but it’s good. [The algorithms] know me well.”

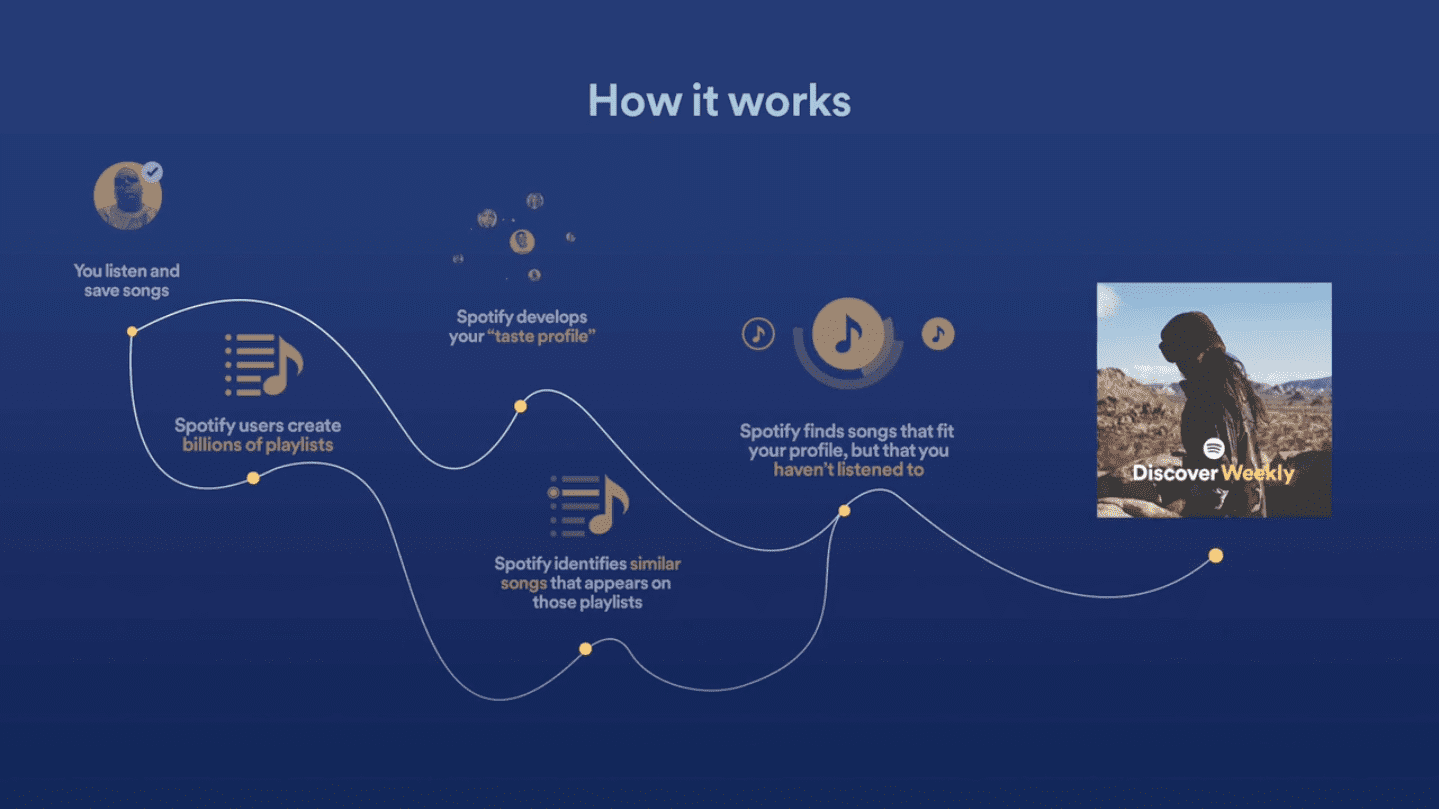

Every Monday, Spotify releases an auto-generated “Discover Weekly” playlist for every user that’s personalized according to their music preferences. Whereas older generations typically discovered new music through recommendations from friends and hours spent in record stores, Generation Z turns to Spotify. The algorithm can mix artists that have less than 100 listeners with famous artists that have millions of listeners. It filters everything according to data collected on your music taste and produces a list of songs the algorithm believes you might like.

Interestingly enough, records are ironically making a comeback even though streaming services offer far more options for a decreased cost. Some argue that we live in an age of nostalgia because many millenials and Gen Z-ers are expressing an obsession with living in a different time. Polaroids are taking over Instagram, vintage fashion is considered artsy, and more and more record stores are popping up in hipster neighborhoods. This nostalgia could be part of our generation’s vested interest in projecting a personalized aesthetic (in this case a retro one) and unique version of yourself. Or it could be the pleasure of discovering music in person.

“I prefer the physical aspect of record shopping because there’s something really magical to me about a needle and a piece of plastic,” said Eleanor Roosevelt College junior Yassamin Emadi, an aerospace engineering major who has had a Spotify account since she was in middle school and was recently gifted a record player. “But when I’m looking for new music, record shopping isn’t my go-to because I tend to go according to image — for what looks the coolest. Whereas with Spotify Discover, I’m actually listening to new music that matches the genre of what I already know I’m interested in.”

Granted, algorithms aren’t perfect. Sometimes, instead of introducing you to something new, they keep you stuck with what you already know. That’s the irony of Discover Weekly: you might not be listening to any new genres at all. Similar sounds become repetitive and then eventually blur into white noise. Music becomes a headache instead of pleasure.

“Since I’ve used Spotify so much I do get a lot of repeats,” Emadi said. “It’s at those times when I realize that Spotify is not a human, it’s just an algorithm. But when the new music comes up, it’s usually pretty promising.”

All of my personal music is streamed through the Spotify app, which I have on both my phone and my computer. Every Monday, I go through my Discover Weekly, and usually forget to turn it off, leaving an endless, auto-generated stream of similar sounds playing in the background until I can’t stand it anymore. A few weeks ago, I decided I didn’t want to listen to more of the same, so I turned on the radio. I landed on a jazz station — a sharp deviation from my usual beach goth — but I stuck with it, and found myself pleasantly carried away. I realized that I’d forgotten what it felt like to be surprised by any other type of sound.

Images from MeTv and Hunters and Thompson.