Trinh Mai develops a powerful monument to the lasting effects of war and diaspora.

It’s been more than 40 years after the formal declaration that ended the Vietnam War, but for the millions of mainland Vietnamese and diaspora communities, that watershed moment of modern global conflict is far from over. In her exhibit “That We Should Be Heirs,” California-based artist Trinh Mai, the daughter of Vietnamese refugees, attempts to reconcile the transcendence of war across space and time, arguing that the war has materialized beyond militarized violence and can be seen in the traumas inherited from refugee parents. For Mai and millions of other refugee children, the experiences of war are not always explicitly told to them by their parents but are rather internalized and picked up upon throughout their lives. In a poignant artistic move, Mai invites viewers to engage in a process of collective recognition and burial, as a means to acknowledge our responsibilities as heirs to our parents’ grief, and find ways to promote communal healing and strength.

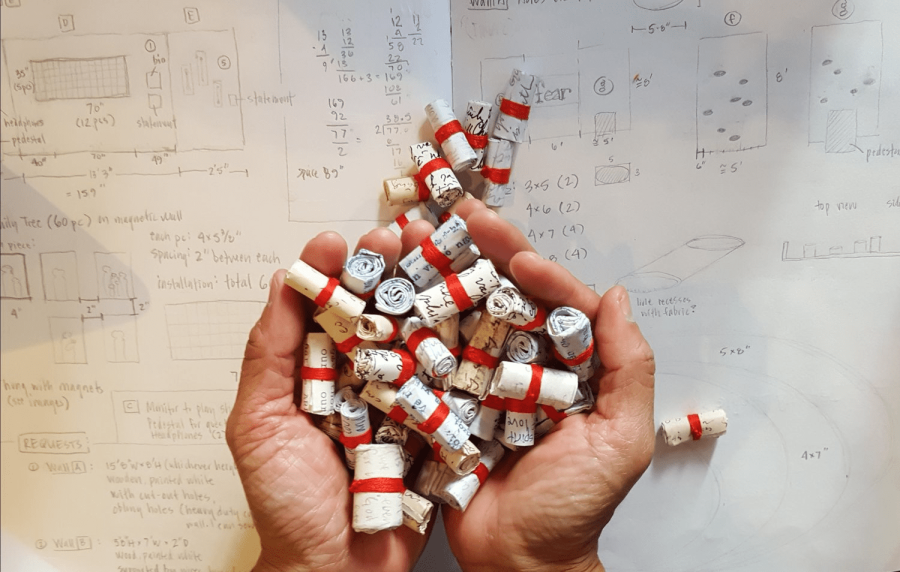

As the titular centerpiece of the exhibit, “That We Should Be Heirs” invites visitors to write their thoughts and fears on small sheets of paper. These thoughts remain anonymous and unread, folded into tiny scrolls that are tucked into a number of pockets (graves for the burial of our fears and burdens) that have been carved out of the gallery wall. Mai’s artistic vision is rooted in the Vietnamese belief “that if the dead are not given a proper burial, their souls cannot rest.” For children of refugees, Mai’s installation, which includes personal letters inherited from her own grandmother, prompts an introspection into our own troubled relationships to our familial and national homes, and lifts the burdens of intergenerational trauma. Mai does not intend for the installation to exclusively be a refugee space but rather to be an open and compassionate space for all patrons to engage in a collective recognition of communal pain. Two additional interactive pieces, titled “Fear Not.” and “Together” invite patrons to participate in erasing the word “fear,” which is etched in with graphite on a 42-by-72 paper canvas and freely interacts in the creation of the word “together” on a 42-by-96 canvas. Together, these works are representative of Mai’s aim to collectively redress our fears. However, that the installation openly invites visitors without direct refugee experience to participate may produce a certain anthropological gaze that disrupts the power of healing in what could be a unique refugee space. Not to any fault of Mai, it should be noted that the San Diego Art Institute is a bourgeois contemporary art space whose patrons are largely white. As exceptional as Mai’s installation is, it should be asked whether this openness may sterilize the focus on the refugee subject.

Mai’s installation features a variety of non-interactive pieces depicting refugee experiences and the contested relationships that second-generation children have with their homelands. One of the first pieces in the exhibit, titled “For We are Called to Freedom,” features a flock of white birds flying mid-air, with small red crosshairs stitched onto each bird, on two 42-by-60 and 42-by-50 paper canvasses. Mai uses the Vietnamese greenfinch and American goldfinch as symbols of cultural confluence, evoking the two halves of the Vietnamese American identity, as well as the quest for freedom that saturates the discourse on refugee flight. For Mai, the deliberate placing of crosshairs on the birds’ hearts represents the targeting of refugees on both Vietnamese and American fronts — from the threat of war at home to white supremacist violence abroad — as well as a point of convergence “at which we can meet to discuss the changes that serve the betterment of humanity.” Mai’s hand in her use of charcoal is subtly impeccable, with the gallery lighting rendering the birds almost invisible on the white canvas. Here, Mai demands a heightened interaction with the piece that reveals that the birds are in fact fading upwards into whiteness, struggling for freedom. Mai challenges ubiquitous narratives of U.S. exceptionalism in which America is a site of freedom that is always aspired towards. Her painting reminds us of the racialized violence that many refugees were met within the U.S., as well as the pertinent threat of deportation that thousands of refugees are facing under the current administration.

Trinh Mai’s “Heirs” is altogether a stunning installation in contemporary refugee art. Mai’s work poignantly touches on the unique experiences of second-generation refugee children, inspiring a process of introspection and healing that is at once moving and empowering. While the politics of art distribution and accessibility may dislodge some of the power inherent in the exhibit’s confrontation of fear, “Heirs” is nonetheless a unique and brilliant work that is deeply personal and rich in cultural motifs.

“That We Should Be Heirs” opened at the San Diego Art Institute on Feb. 16 and will continue to be shown until March 31.

galSlulk • Feb 27, 2019 at 11:15 am

We are happy to announce you that you are eligible to get online loan,

The process is very fast and totally free, just in less than five minutes and the amount can be between $1,000 – $50,000

If you would like to hear more details please leave your number and we’ll get back to you ASAP