Going to the library I saw a girl gathering signatures to ban the Woody Allen film class at UC San Diego since his daughter Dylan Farrow accused him of pedophilia. I disagreed with the petition so I have decided to explain her why will I not sign it. I said, “First, the evidence is inconclusive. Secondly, most Woody Allen movies have nothing to do with his alleged pedophilia.” Well, in response I got screamed at: “Why do you need so much evidence to believe the survivor? When will we stop failing the survivors?” She assumed that I could not sympathize with the victim or that I could not take the victim at her word. But the issue is much more complicated than she — and others — made it out to be.

The girl promoting the petition asked me why I was so interested in Woody Allen’s case. I had many reasons but I named only one: From the age of 14 until the age of 18, I have been abused by several men, one of them was my history teacher, who had been assaulting his students for over 16 years. His case went viral and now similar cases take their toll on me. How ironic it was that the girl who assumes the universal role of the survivors’ defender, at this very moment, was screaming at one, fully aware of my situation but unwilling to even entertain my arguments. It’s not only ironic but also very common.

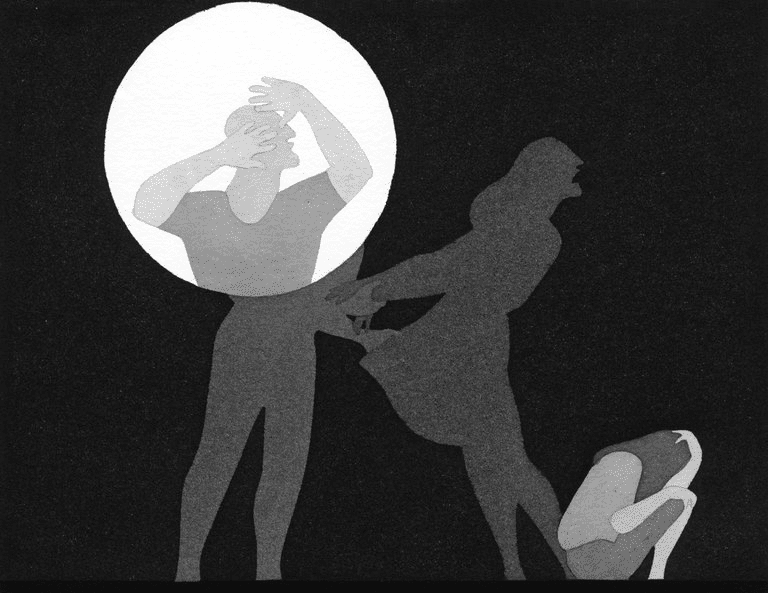

“Inaction is an action, silence is indifference, justice requires action and a voice” — this is what judge Rosemarie Aquilina said after sentencing Larry Nassar to 175 years in prison for numerous sexual assaults. Seemingly this sentence is designed to help victims, to push them to break their silence, which would — according to some — help them heal. However, not all victims are the same, and not all of them would benefit from going through an excruciating persecution process. In fact, under certain circumstances, it might damage them such that they will never recover. When adapting a rhetoric where all victims are treated the same way, feminists neglectfully sentence part of them to a miserable existence.

There are plenty of reasons why victims do not report their abusers and to understand that we must tackle a myth that most assaults fit the stereotype of the night-time attack with a mask and a knife. According to the National Violence Against Women Survey and Bureau of Justice Statistics, the vast majority of rapes and sexual assaults are conducted not by strangers but by friends, teachers, live-in partners, and relatives in the victim’s apartment, school, and other supposedly safe places. A victim who knows his or her abuser is much less likely to report the case than the ones that do not. Why?

It is extremely hard to vilify a person you know. The notion that one can so unilaterally assign blame to the abuser does not always register in a victim’s mind, especially when these sentiments stand opposite to past experiences with the abuser. You might have known the person from your childhood, he might have simultaneously helped and hurt you, he might have sincerely apologized one hundred times. The behavior of an abuser and the behavior of someone who is sincerely sorry overlaps much more so than people realize. Therefore, for victims, it is not nearly as black-and-white for us as for onlookers, or for a judge bound by law rather than human emotions. Persecuting someone when you are not sure whether you are right or wrong is the worst thing that can happen to you: Blame keeps you up at night and anxiety wears you down. In these cases, you need to heal before you prosecute and silence will help you to survive.

Besides, even if it is not your friend who abused you and everything seems rather obvious from the side, one of the most common complications that victims might develop is a psychological phenomenon called Stockholm syndrome. Stockholm syndrome is a protective mechanism that causes victims to attach to their abusers, sometimes even fell in love with them. It does not matter whether the victim knew the abuser before the abuse, what matters is that the victim spent an extensive amount of time subjugated to his or her abuser. Apart from that, the prosecution involves continuous exposure to trauma: Everything has to be retold, repeated, and challenged. It is hard to even without all these other aggravating circumstances to follow through the process, but with them, the prosecution might damage the victim forever.

Apart from victim blaming, in the quest of punishing more sex offenders, feminists also fail to tell you at what personal cost this prosecution will come to you. They tell you that they will support you, that you will get all help in the world when you are going through with a prosecution and that you will be able to recover quickly. On campus, the Sexual Assault Resource Center and A.S. Women’s Commision try to plant this idea. However, support is just a word until someone actually needs it. From my personal experience, I can say that it is not true. I knew that I needed psychological support right away: Even before the case started I went to CARE, to CAPS, to the Women’s Center, and ultimately I did not get help. When my case went viral, my life that was previously kept together by a thin string fell apart, and I still did not get help. If I knew that this would be the support I would get, I would probably restrain from promoting the case.

But UCSD is successful in creating illusions. While it might seem that it helps survivors to heal by pushing them to “break the silence,” in fact, it frequently leaves those survivors in ruins.

Dr. Necessitor • Feb 14, 2018 at 3:42 pm

Great opinion piece! Very well written. I hope you find the peace you deserve.

samantha geimer • Feb 13, 2018 at 3:39 pm

That is an amazing read. Truth is not always popular.