Scientists at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the Western Australian Museum published a study in the Marine Biodiversity Records journal on Jan. 13 describing the first discovery of the ruby seadragon in the wild.

According to Josefin Stiller, a doctorate student at the Scripps Institute and co-author of the study, the discovery was unexpected. Stiller’s primary research concerns the leafy and common seadragon species that live around Australia. The study began two years ago and examines how past environmental changes have affected seadragon populations.

“For our work, we sequence the DNA of many individuals of the better known species, common and leafy seadragons,” she told the UCSD Guardian. “Most of our samples come from small tissue clips that we take before we release the animal. Some others come from museum samples. Such a museum sample, a piece of tail sent to us as a common seadragon, turned out to be genetically distinct from all of our samples of common and leafy seadragons. This was our first indicator for a new species.”

Following this realization, Stiller and her colleague Greg Rouse, a professor at the Scripps Institute and a co-author of the study, requested additional information from the museum and found that there were a number of anatomical differences between the museum sample and the leafy and common seadragons.

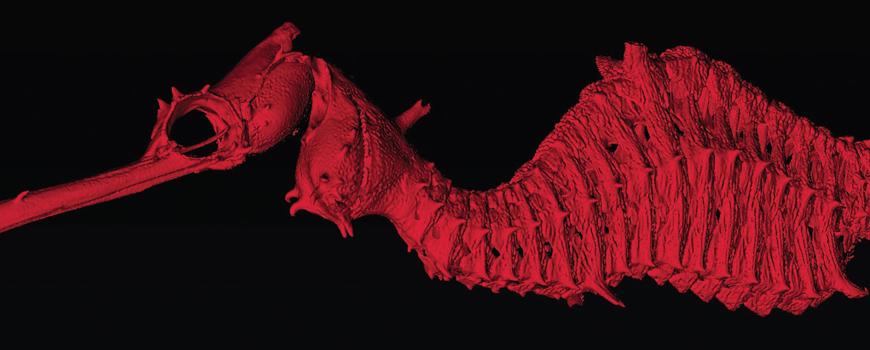

“We received a photo showing the bright red coloration, which is not found in the other two species,” Stiller explained. “We were also loaned the specimen and found that there were a number of differences in the skeleton.”

In order to prove that this was a new species of seadragon, the team visited southern Australia, where it used a small robot to capture footage of the fish.

“The observations of living ruby seadragons in the wild showed two surprises,” Stiller elaborated. “First, the species lacks the skin appendages which are so characteristic of seadragons. Secondly, we saw that the fish can curl its tail. A prehensile tail is something we do not see in the other two seadragon species.”

To help camouflage with their kelp habitat, the leafy and common seadragons have developed dermal appendages that resemble kelp. However, the ruby seadragon lacks these features because it lives in more open waters. In addition, according to the study, the animal’s red color may be a camouflage strategy for its low-light habitat.

Stiller described the discovery of the new species as a very exciting moment.

“We were watching the video feed from the dive robot on deck and all of a sudden, the fish appeared,” she explained. “After almost two years of imagining this species in the wild, there it was.”

Stiller and her colleagues recommend the ruby seadragon be placed under protection as soon as possible. The other seadragon species are already on the protected list.

With regards to their research, Stiller and her colleagues continue to study the leafy and common seadragons.

“We have collected our final samples for the genetics study of the other two species in Australia,” she told the Guardian. “We are also working on gaining a better understanding on the evolutionary relationships of the seadragons and all of their diverse cousins, the seahorses, pipefishes and pipehorses.“