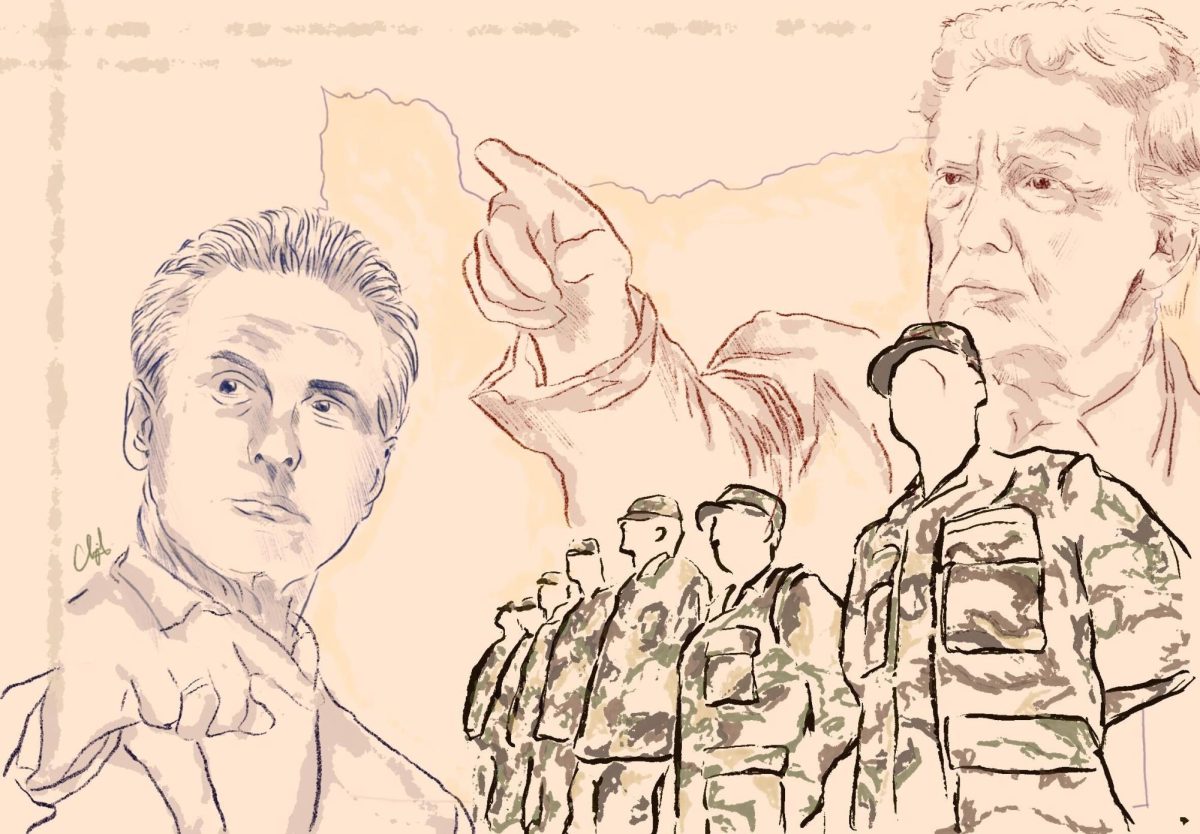

STATE NEWS — State Senate Majority Leader Alberto Torrico (D-Calif.) pitched a new bill in February that would pump almost 10 percent of California oil profits into higher education. But, as tempting as this modern Robin Hood system may be, we can’t lean the fate of an already dwindling higher education on a depleting natural resource.

The bill would eventually generate over $1.5 billion a year by placing a 9.9% tax on in-state oil drilling, and could theoretically put an end to professor furloughs, climbing student fees and swelling class sizes. Of that $1.5 billion, $270 million would be designated to the UC system, $540 million to the California State University system and $99 million to community colleges (despite the fact that, with an enrollment of nearly 3 million, they boast over ten times more students than the UC).

The fact that both UC and CSU officials have taken a stand against the bill — despite the fact that it’s supposed to benefit them — is especially telling. Their major concern: If state government higher-ups believe oil companies are providing public colleges and universities with sufficient funding, they might cut state funding even more to free up money for California’s other myriad of problems — leaving us sucking from a drying industry.

For the 2008-09 academic year, the state provided the UC with a total of $3.2 billion — and for this year, that figure’s already down by a massive $843 million. If assistance from the big oil companies creates the illusion of financial stability, there’s no telling how much deeper state cuts might run.

While the revenue generated by the bill might momentarily ease some of the symptoms of the budget crisis, we can’t afford to ride the coattails of our oil industry off into the sunset, especially if it means jeopardizing our rightful source of funding: the state.

In theory, funneling cash from evil corporate giants seems like the perfect solution, but it’s not nearly that simple. Oil, after all, is a nonrenewable resource. Once we’ve siphoned it all into our Escalades, we won’t be getting it back anytime soon. It would be far wiser to look into growing resources like renewable energy for funding, rather than one with a heaving finite limit .

In the past seven years alone, California reserves have run down 300 million barrels, and the state industry has been on a downward slide ever since its peak of productivity back in 1985.

Some argue that — because California is the only major oil producer in the United States that doesn’t demand a severance tax on the industry — it’s time higher education jumped on the oil-levying bandwagon. Granted, other states have used oil profits to their benefit. Texas, for instance, sets about $400 billion aside every year from mineral and oil profits for higher education. But with a comparatively paltry 1.4 million students (the Golden State boasts 3.6 million) and 40 percent greater oil production, an oil tycoon’s dollar won’t stretch nearly as far in California.

With such great differences in context, Texas’s solution may not be as one-size-fits-all as we’d hope.

Assembly Bill 656 is hardly the first of its kind. In 1981, 2006 and again this year, proposals to tax California’s oil industry have crashed and burned — primarily out of fear that such a tax would drastically affect consumers at the pump (a scare tactic employed by the oil giants funding the con campaigns).

Instead of just looking at the short-term, we need to step back and consider the possible outcomes of this quick fix. Majority Leader Torrico said his bill will help public universities systems raise more money to support the state’s ever-growing student population. But redirecting oil profits wouldn’t be the enduring systemic change we need — instead, it would slap a convenient band-aid onto a gaping slash in our budget.

Though the bill is an innovative effort to simultaneously provide revenue sources for our schools and put pressure on the big guys depleting Earth’s resources, the funding hunt can’t end here: AB 656 should be a mere jumping point to better-reasoned proposals. Though lobbying policymakers at the capital for instance (as UC President Mark G. Yudof has proposed) is far from a surefire launch out of our budget crisis, it would at least avoid making private companies responsible for bankrolling our education.

Yudof’s and Torrico’s proposals should both be commended for at least putting new solutions on the table — but for any kind of sustainable change, we need to get more creative than targeting a cash-strapped state and a few rich oil bandits. Taxing other lucrative industries with guaranteed business or loosening state laws to make way for new ones (read: legalize it) could pull our universities out of the red. Policymakers must follow Torrico’s lead in proposing innovative solutions to higher education’s problems — it’s our only hope for a furlough-free tomorrow.

Readers can contact Cheryl Hori at [email protected].