Christina Roh talks about environmental racism, intersectionality, and toppling Tesla.

“I went to a really progressive all-girls school in LA. That seems like an oxymoron, but it was actually a very liberal, cool school that taught feminist studies as well. That was kind of my first introduction to these issues.”

Since these early beginnings, Christina Roh has wholly immersed herself in activism.

In her day-to-day life, Roh wears many hats. She is an intern at the Women’s Center, an all-campus resource that places the experiences of diverse women at its core, and the director of Civil and Human Rights at the Student Sustainability Collective, an Associated Students-funded, student-run collective that heads projects related to eco-friendliness. The position centers around bringing an intersectional approach to sustainability — a role that seems like it was perfectly created for the 4th year Environmental Systems student activist.

The concept of “eco-friendly” is never framed in the context of race, gender, and class, Roh tells me. Roh explains the problem of environmental racism, a type of racism that occurs via environmental policy and decisions, and why the sustainability movement can sometimes be unfair to certain marginalized groups.

This would culminate in her proudest achievement at UC San Diego to date: a panel exploring the hypocrisy of green energy in America. Roh gushes about mentor and role model Leslie Quintanilla, leader of the UCSD Center for Interdisciplinary Environmental Justice and professor in the department of ethnic studies, who she collaborated with on this panel.

For context, Roh tells me of Central America’s “Holy Trinity:” Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile, home to the richest lithium deposits in the world. Lithium is highly valuable in the U.S. as the main component of rechargeable batteries — such as the ones in Tesla cars. Tesla, whose stated mission is to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy, has seen an increase in popularity in recent years as a valid alternative to gasoline cars. In response to this demand increase, Tesla has begun sourcing lithium from the Holy Trinity, attempting to buy the property rights to lithium rich lands from their governments. Colonialist implications aside, this poses a considerable environmental problem: the lithium deposits are in lake beds, accessible only by evaporating whole lakes.

And the racism problem? Indigenous peoples have lived off the land for generations, relying on those lithium-rich lakes for water supply.

The true cost of environmentalism comes out. This debacle illustrates Roh’s message perfectly; in Tesla’s journey to transition rich environmentalists to sustainable energy, they have trampled the lives of innocent people.

The irony of destroying ecosystems in another country in the name of preserving the environment in our own is not lost, either. It is classism and racism neatly justified as environmentalism for the select few.

“Green for whom? That’s what I always ask,” Roh said. “Yes, it’s green for us, but it’s also killing people.”

A joint SSC and CIEJ event organized by Roh and Quintanilla brought four indigenous leaders from Holy Trinity countries, Chile and Argentina specifically, to UCSD to speak about their experience with the depletion of their land and resources and ways they continue to fight back against corrupt governments who value money over the well-being of its people.

“The connection to the environment from indigenous people is so different from how we perceive it here,” Roh said. “A lot of how we view sustainability is really not close to being as sustainable or as well rounded as indigenous practices at all. It was beautiful to hear them talk about the stories they had with nature, and all the stories they passed down through generations … I was beyond thrilled. There was so much love in the air and in the room.”

The power imbalance in the environmentalist movement today is not new and has long standing roots.

“I did an event about why the outdoors industry is so white. Like, when did becoming interested in the outdoors become such a white thing?” Roh asked.

It’s because environmentalism has an unfortunate history of excluding people of color, she explains. This pattern can be traced back to Madison Grant, eminent conservationist and close friend of Theodore Roosevelt. Grant was also a supporter of eugenics who published “The Passing of the Great Race,” a manifesto warning of the decline of the Nordic race if the gene pool was not properly maintained. Roosevelt, who later founded the National Park Service, praised the book.

“Hitler called that book his Bible,” Roh added helpfully.

To these men, the great outdoors was a mark of aristocracy, and its preservation crucial to the preservation of the aristocratic race. Even though environmentalism has come a long way since its founding by racist activists, it’s not hard to see the outstanding bias.

Green for whom?

Roh wants to open up the outdoors to such historically excluded groups — beginning with her own. The Korean-American activist is currently in contact with Outdoor Asian, an organization that primarily focuses on getting Asian communities more involved with the outdoors and more involved with the environment. Roh hopes to start a chapter of Outdoor Asian in her hometown of Los Angeles, where she lives with her mother and younger sister. The mission of Outdoor Asian is particularly relevant to Roh, as an Asian-American for whom appreciation for the outdoors was an acquired taste. Roh’s mother once scoffed at the idea of camping, seeing no intrinsic value of paying money to sleep on the dirt outside. “I’ve kind of internalized this, and this seems to be a common experience among many of my Asian-identifying friends,” Roh said. Nevertheless, Roh does lightheartedly note that there is a significant population of Korean grandmas that frequently go hiking together in LA. Roh hopes Outdoor Asian will help get more of that going.

Read more:

The Ocean Lovers Club and Their Mission to Clean Up The Oceans

Thank You for Making Art for Us: 10 Years of A.S. Graphic Studio

Professor Watts and the Wonders of the Past

Environmentalism has other barriers for entry, and Roh has also been doing research specifically on barriers to sustainable menstruation products. One of Roh’s long-term projects is trying to determine how to make sustainable menstruation products, such as menstrual cups and fluid-absorbing period underwear, more widely adopted and if factors such as price, stigma, or education play a role in their accessibility. While she hopes to work with local homeless shelters and organizations outside of UCSD to reduce menstrual waste, Roh acknowledges that it is difficult to expect people without consistent access to clean water or laundry facilities to switch to reusable options.

“This isn’t just an environmental issue, it’s a human rights issue. People don’t even have enough tampons or pads … [they should have] literally anything so these people can just go on with their lives without getting toxic shock syndrome.”

In addition to her Civil and Human Rights programming at SSC, Roh also plans and leads Gender Buffet at the Women’s Center, a weekly informal discussion about social issues. This week’s topic was De-Stigmatizing STIs, but previous Gender Buffets included a movie and craft session for Valentine’s Day, and a panel with several black activists at UCSD.

“We usually like to bring in other orgs, give them a spotlight, give them a platform, and go from there,” she said.

After all, the crux of intersectionality is stepping down and allowing others to speak up, and Gender Buffet was where Roh first learned about intersectionality; she came to one Week 2 of freshman year and has since been hooked.

“I’m not gonna lie, I was ignorant when it came to a lot of issues specifically regarding race; I was super into ‘end sexism’ without talking about the racial aspects. When I first started getting interested in racial politics and intersectional feminism, it was through the Women’s Center.”

Roh has stepped into the shoes of those before her. Candidly admitting that she has re-shaped her activism over time, she is dedicated to creating a space at the Women’s Center where all are welcome as long as they are open to learning and occasionally confronting uncomfortable truths.

And that’s just the nature of activism.

“It’s kind of disheartening sometimes, I feel like a lot of people often question – why does this matter, why do you care so much, why are you trying to make this so political? And I tell them that they have the privilege to experience these things without it being political. I mean, do you not care about other people?”

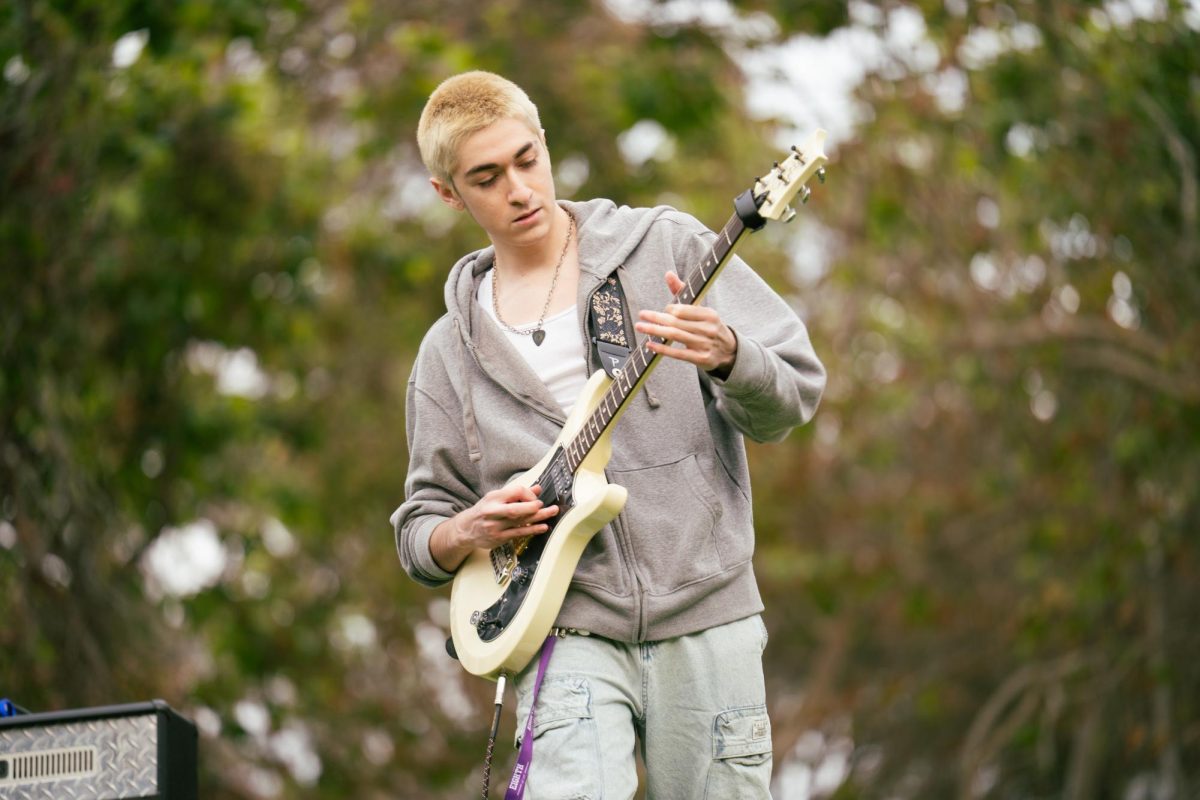

Photo courtesy of Christina Roh.