It’s easy to leave the events of the last school year in the past, but the fight behind last May’s UC workers strike is still very much alive. The Guardian spoke with AFSCME about the new school year in the context of their ongoing struggle for equality.

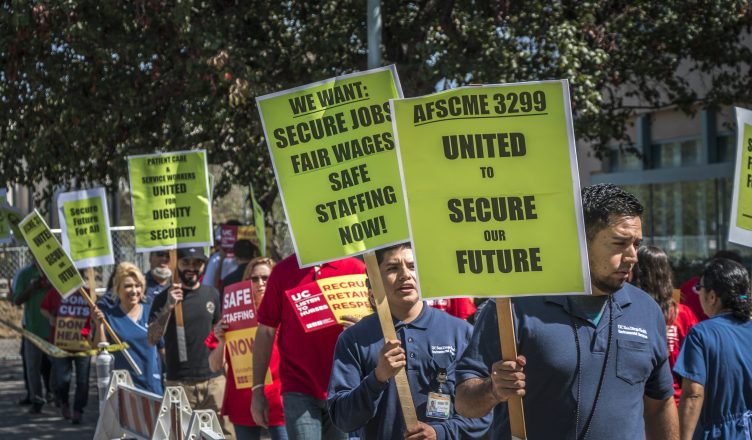

For three days in May, UC San Diego was in a state of unrest. Strikers from the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees 3299 — an organization of UC workers — demonstrated all throughout campus. Stemming from contract disagreements with the UC system, the workers demanded a wage increase that kept up with the rate of inflation, and an end to wage gaps between workers of different race and gender. With each footstep, they incited recognition and solidarity for their fight in onlooking students.

But that fight is not over. Though campus may have quieted down after the May 7 to May 9 strike, the union remains in the bargaining process with the University of California. In fact, UC negotiators refused to meet with AFSCME 3299 for an Aug. 29 bargaining session at the UC Davis Medical Center, even though they’d previously agreed to do so.

“UC [negotiators] actually called to cancel [our bargaining session], stating that workers don’t need to be a part of the bargaining at this point in the process,” said John de los Angeles, the union’s communications director.

Frustrated by the UC negotiators’ silence throughout this bargaining process, the union announced on Sept. 26 that their members will be voting on whether or not to strike again in the coming months.

With another potential strike on the rise, the struggle for UC laborers’ voices to be heard is still very much ongoing. Ruth Zolayvar, a union member who works at Jacobs Medical Center, understands firsthand how much still needs to be done for workers’ rights. Zolayvar is currently part of the union’s team of negotiators for both patient care and service workers.

“There is a growing inequality in [the university] when it comes to race, gender, and wages. So it’s a growing thing. All we need to do is keep on fighting,” Zolayvar remarked.

Zolayvar appreciates that AFSCME empowers her to fight for her equality, especially since she was unable to exercise this same freedom of speech in the Philippines.

She recalled, “In 2013, I was just barely getting to the university and I could see people going outside fighting. In the Philippines, it’s really hard to fight, but over here you have freedom of speech, so that’s when I joined and … I like it here in the U.S. because of the freedom I can express.”

Since arriving at UCSD several years ago, Zolayvar has held a number of leadership positions within the union, with responsibilities including keeping members informed and pushing the state to back worker benefits. Zolayvar is currently working to bring the struggles of the union members to the state level.

“Our goal is to win a contract that respects the work that we do, a contract which takes care of our families and our futures. A contract that addresses the growing inequality in regards to income, gender, and race. And we want [the university] to stop outsourcing our jobs. And do we see any progress? We don’t know,” declared Zolayvar.

Indeed, the progress toward equality has been so slow-moving it’s almost indiscernible. What’s been easier to trace are the disadvantages that are arising thanks to the university’s bureaucracy.

Zolayvar noted, “[UCSD’s higher-ups] make more and work less — they travel a lot, they have lavish dinners, and these salaries between executives and us workers are widening. We should stop the widening gap between the executives and the workers so we can provide services to the students.”

That’s not to say, however, that the union has been without their victories. The May strike proved to be an exceedingly successful display of the union’s grievances and brought a flood of support from onlookers.

“It goes without saying that the general public doesn’t pay attention to labor disputes very often. We had 53,000 members statewide and I think we made a very loud statement. We brought the issue of pay and benefits and treating workers that live around [the university] with respect by providing them with career ladders. I think we brought that issue to the forefront with the type of media coverage that we got,” reflected de los Angeles.

Zolayvar agreed that the strike was an immense success. She said, “For exposing the inequality of UC, for 53,000 workers standing strong, the strike was a big success. And UC knows all this. We want UC to address these inequalities.”

After reflecting on the injustices she’s faced as a worker, Zolayvar remarked that students are facing similar inequality as UCSD continues to impose inexplicably high tuition fees. In essence, rather than slimming the bureaucracy to offset cost, UCSD passes the consequences on to students and workers alike.

Our goal is to win a contract that respects the work that we do, a contract which takes care of our families and our futures. A contract that addresses the growing inequality in regards to income, gender, and race. And we want [the university] to stop outsourcing our jobs. And do we see any progress? We don’t know.

De los Angeles added, “[The university] just supposedly lowered tuition. Do you actually know the dollar amount that they decreased tuition by? It’s only sixty dollars. Six zero. To count that as a win for students is a little ridiculous … I’m gonna let you tell me how much $60 buys you in a week. When we’re talking about this inequality, we’re talking about more than just the $60 increase that needs to be done to fix this problem.”

AFSCME is well aware of the parallels between the issues of student and laborer inequality, and has teamed up with student organizations to discuss their advocacy. Students have also been involved with the union’s efforts, showing solidarity for their cause.

“We have a history of our students going to our actions. We also go to students’ club meetings and support one another because the struggles are real,” stated Zolayvar.

With the onset of another academic year, AFSCME would like to see continued integration with students. In particular, one of the union’s goals for the new year is for students to recognize that their struggles are linked to that of laborers by a common enemy.

“Workers are currently being asked to make even less, but at the same time there’s ongoing conversation about tuition for students,” de los Angeles observed.

“With the rising cost of education and the lowered value of the workforce, all are driven by the same thing here which is [the university]’s desire for profit. We’ve seen, over the last several years, the gap between the top and bottom of [the university] grow exponentially. One of our goals for the new year is for students to recognize that we’re together on this.”

One consequence of the university’s profit motive is the rift between laborers who struggle to find work and students who take positions in labor fields. As students don’t have a union to ensure fair pay and hours, they are often filtered into on-campus labor positions, narrowing down job options for non-student workers. Recognizing the institutional forces behind conflicts like this is the first step toward dismantling these injustices.

Despite the different roles that exist within the UCSD community, a social justice movement at any level naturally involves people from all types of backgrounds, from student to laborer. Recognizing and being present in the union’s efforts offer students an entry point for social justice conversations that build on what they learn in the classroom.

Zolayvar explained, “We want new students to practice social justice beyond the classroom. This is a chance for students to learn the progressive values that [the university] teaches. They must go outside of the classroom to see this.”

Photo by Mihir Desai