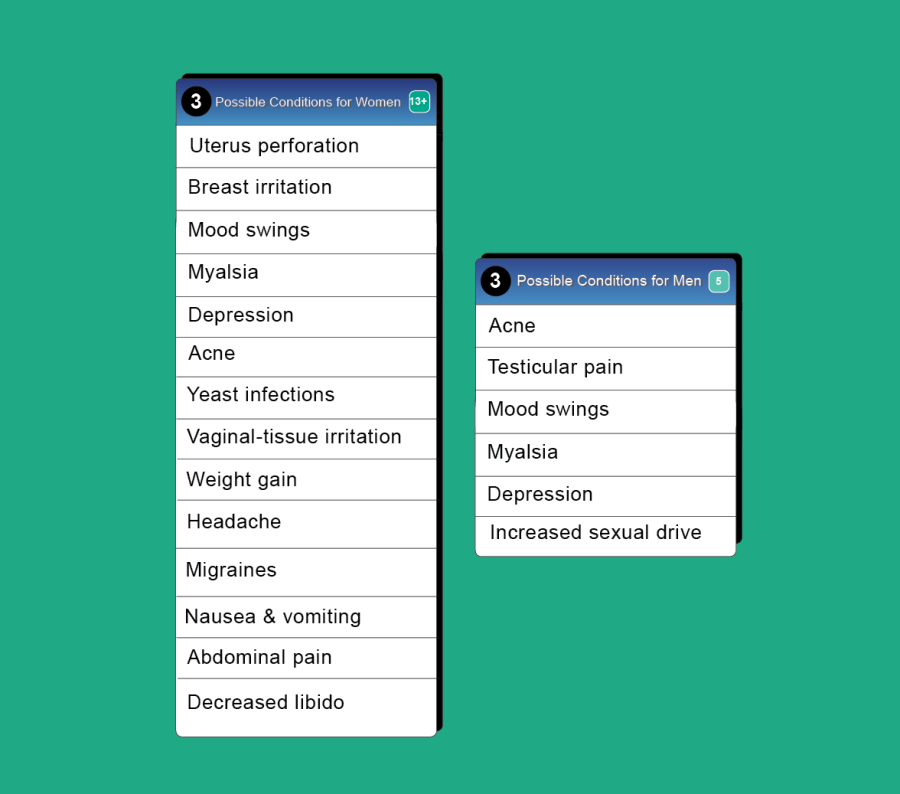

When news broke that a study for male contraceptives was halted earlier this week, it was the participants who had dropped out of the study due to acne, mood swings and pains that took the forefront of reproductive health dialogue. In the eyes of many, they exemplified what happens when men are even temporarily forced to bear the burden of contraceptives’ side effects, which as many as 60 percent of women face today.

In many respects, this is the case: Contraceptives for women have equal, if not greater, side effects, including additional breast irritation, uterus perforation, yeast infections and vaginal tissue irritation. Even more, the entire burden of what happens post-sex rests on the shoulders of women. What was missed by Cosmo, USA Today and other sources centering the study’s livelihood on these participants, is that an independent review board — not the 20 drop-outs — fully necessitated the study’s end by citing safety concerns. It’s those concerns that speak the loudest about what constitutes an “acceptable” side effect for men in comparison to women.

Laying down the study

The board’s reasons for that particular decision are unknown, though it was reported that the study’s 320 participants reported a total of 1,491 adverse events, 900 of which were cited as being caused by the contraceptive. 50 percent of participants reported acne, 38 percent reported increased sexual drive, 20 percent reported a mood disorder, and 15 percent reported muscle pain. Alas, 75 percent wanted to continue using the drug, a combination of injection and testosterone.

Side effects like depression are nothing short of concerning, but similar ones failed to prevent Liletta, a contraceptive sold to women, from being produced. Compared to the 2.8 percent depression rate in the trial for men, the rate for Liletta amounted to 5.4 percent. A more structural problem with the study is the lack of pre-screening for depression. Though one participant committed suicide, with another attempting, the implication of these cases is inconclusive due to the lack of pre-screening. All in all, future studies on contraceptive for males need not only to be more common but better-designed so that missteps stop keeping the drug from hitting shelves in a less harmful form.

Background on Birth Control

Still, even if some side effects are comparable between genders and, in the eyes of some, necessitate a halting of the study, the threshold for halting a study when women are involved versus when men are involved is worth looking into.

Earlier studies in contraceptives for women saw far worse side effects without halting. As explored by Bethy Squires of Broadly, trials like “La Operacion,” conducted in Puerto Rico in the ‘50s and ‘60s — when contraceptives were illegal in most U.S. states — entailed Puerto Rican women being sterilized without their knowledge by researchers looking to create a pill that could be sold widely. At the study’s end, 17 percent of participants had undergone stomach pain, headaches and vomiting, and three had died. A tie to the pill was never established because the women’s autopsies never happened, but the drug, named Envoid, still went on to be produced.

These reminders, along with the recent data-backed finding that teenage girls on the pill are more likely to seek antidepressants than their counterparts who are not on the pill, speak not so much as to what men can or cannot handle but with what women have been forced to handle for decades.

Broadening the Scope

What’s more, the comparative amount of irreversible contraceptive measures performed speak to what reversible contraception cannot change alone. The vasectomy and the full tubal ligation, two permanent contraceptive measures available to sterilize sperm and egg alike, are not drastically different by any means in difficulty or cost, but the number of men who have had a vasectomy is 10 percent lower than the amount of women who have had a full tubal ligation. Beyond the need for ample and better studies for the sake of creating birth control for men, there persists — of course — the ongoing view that reproduction is not the responsibility of men.