The Lebanese doctor Elie Fares recently wrote in a blog post: “Their death was but an irrelevant fleck along the international news cycle, something that happens in those parts of the world.” This has been a common response to the lack of international empathy for Beirut in the aftermath of the twin explosions that left 54 dead and 200 wounded in Beirut.

This neglect is not necessarily a result of the lackluster media coverage by American and international journalists but rather the demand of readers who ultimately shape the content of journalism.

It’s all out there — Beirut was covered, as was the attack on a Kenyan university in April which similarly lacked international attention. The New York Times, The Washington Post and BBC covered the event with in-depth investigative pieces and general coverage. Martin Belam, journalist and designer from BBC, recalled that the media coverage of Beirut numbered “over 1,286 articles — lots of which pre-date the attacks in Paris.” But these stories are not read at the high volumes as those about Paris. And so journalists, too, have a right to feel angry, because claims that the attacks in Beirut went unnoticed by major media are false. It’s readers who drive content and decide what’s shared and discussed.

One of the most retweeted photos in light of Beirut and Paris on the night of the attacks was accompanied by a caption reading “No media has covered this” and was actually a photo taken nine years prior in 2006 during Israel’s war against Hezbollah in Lebanon. Above all else, this demonstrates the lack of public interest — no one noticed or even cared to fact-check.

According to Vox, Max Fisher of the Atlantic is a journalist who struggled with what he believes is newsworthy and what actually is, recounting disappointment at his 2010 coverage of the bombings in Baghdad upon being told by an editor that “No one is going to read this.”

At the heart of this disparity is why and how humans empathize. Why, as Lebanese writer Joey Aryoub asks, do Beirut victims not get the thoughts and prayers of beloved celebrities who have the immense power of the Internet at their fingertips? The answer isn’t that simple, but two realities persist, and both reflect Aryoub’s and Belam’s claims.

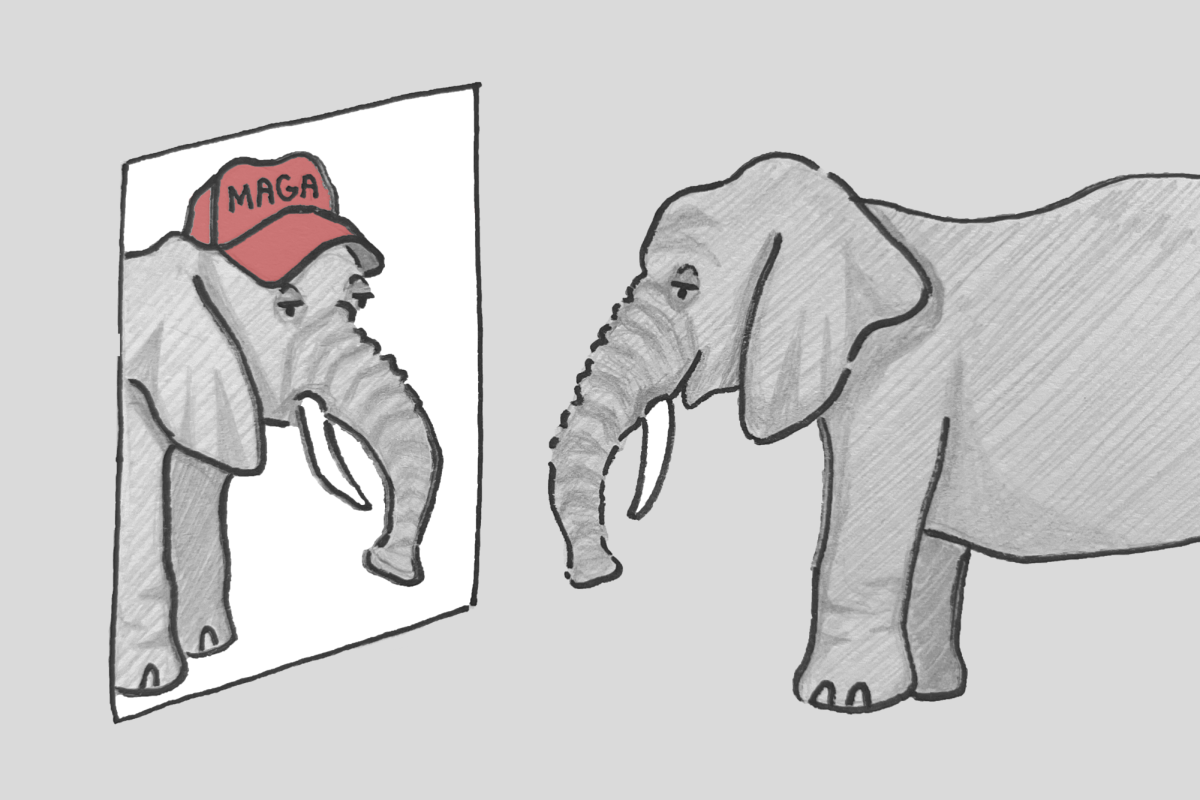

What a lack of front-page news stories and Facebook shares regarding Beirut demonstrates on a deeper level is that people living in the Western sphere do not exercise the same degree of empathy about Beirut as they do about Paris. It’s a familiar part of the West. According to the International Institute of Education, France is the fourth most popular choice for a study abroad destination, while Lebanon does not break the top 20. Clearly, the reports of terror in non-Westernized countries aren’t perceived as attacks on people and are, rather, as Fares mentions on his blog post, merely seen as “something that happens in those parts of the world.”

As elaborated by Justin Peters in a piece for Slate, the articles regarding Beirut lack integral elements of writing that those written about Paris exhibit, from second accounts of the wreckage to narrative storytelling and selection of quotes. This shows increased empathy toward victims of terrorist attacks in more Westernized nations, reflected in part by how these attacks are described to the public as well as how they are received.

With that said, there are generalizations revealed through selective coverage of Lebanon and Syria that contribute to a hierarchy of empathy, in which victims from more Westernized settings receive the most, whether intentionally or not, and little effort is made to understand regions outside of this familiar model of democratic society. This is evident in the claim that Lebanon is a war zone and that the Beirut attacks were typical. It’s certainly located in the politically volatile Gulf Region, but as Anne Barnard states in her analysis of the aftermath of Beirut, this year — despite political assassinations in recent years and an Israeli airstrike nine years ago — had been one of “relative calm” for Beirut. Blanket statements regarding the Middle East in reactions to terrorism dismiss issues that we need to acknowledge.

Time after time, it’s consistently Muslim and Jewish populations who face the greatest dangers after terrorist attacks and who are blamed for violence they did not commit. This week, a San Diego State student was attacked by another student who attempted to push her, rip her hijab from her head and, as reported by Quinn Owen of The Daily Aztec, yelled “hateful comments about her ethnicity.” This is just one of many similar reactions this week in response to previous terrorist attacks, joining the arson and shooting of French mosques after Charlie Hebdo and the brutal attack of a Muslim woman in Toronto who was picking up her kids from school.

For there to be media coverage outside the Western sphere, American readers must work to understand the complexity of countries and affairs in the Middle East and the Gulf Region. Readers need to demonstrate that deaths like those in Beirut are not merely “blips on international radar.”