An eye for an eye. You reap what you sow. And now: “Frankly, these parasites simply had it coming.”

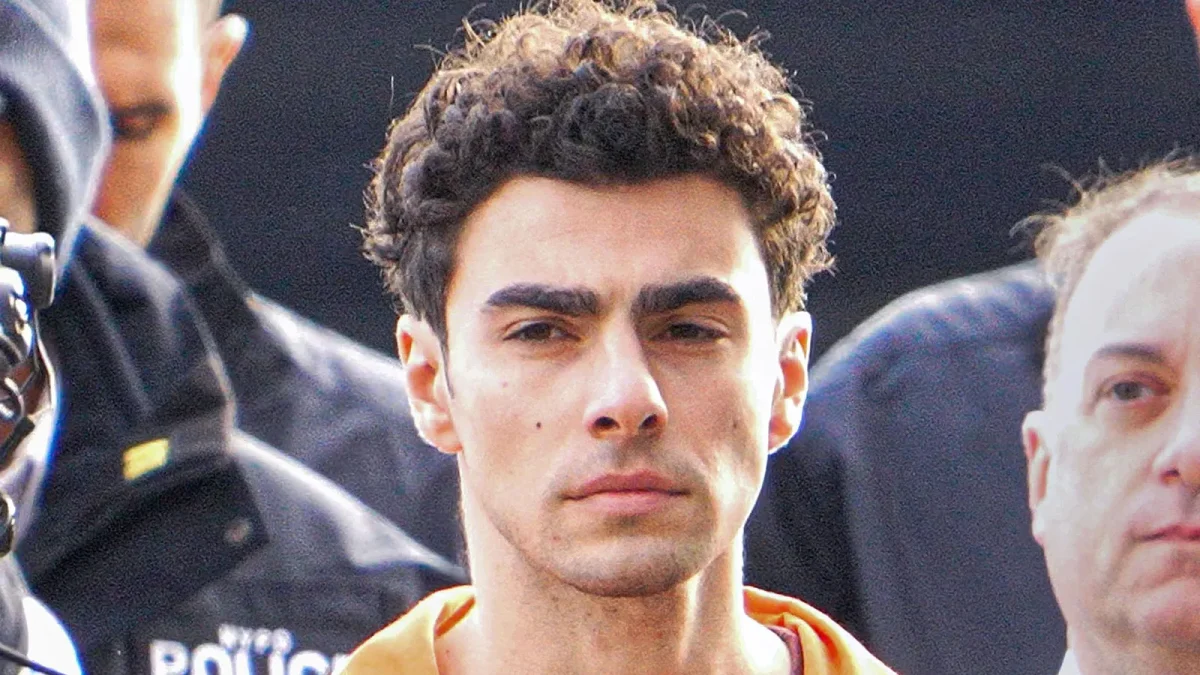

On Dec. 4, 2024, Luigi Mangione allegedly shot and killed Brian Thompson, former CEO of UnitedHealthcare. The public’s reaction was swift — not shock, not sorrow, but something closer to vindication. An Emerson College poll revealed that almost half of voters between the ages of 18 and 29 considered the act “acceptable or somewhat acceptable,” reflecting their deep frustration with the healthcare system. Though this outrage is justified, hailing Mangione as a hero ignores the deeper consequences of legitimizing political violence.

From the legend of Robin Hood to fictional antiheroes like Batman and the Punisher, widespread approval of vigilante violence is nothing new. These figures exist outside the law, driven by the belief that traditional avenues for justice have failed. This approval extends beyond fiction, as seen in the real-life cases of Marianne Bachmeier, who shot her daughter’s killer in a courtroom, or the Louisiana father who killed his child’s molester. In these instances, the direct and personal nature of the harm — the murder of a daughter, the assault of a child, or even a fictional hero avenging a loved one — elicits a moral clarity that society finds compelling. The provocation is undeniable, and the response, though violent, is understandable.

While acts of vigilante justice can sometimes be excused on moral grounds, Mangione does not meet this standard. When Bachmeier fired seven rounds at the man who took her daughter’s life, her reasoning was devastatingly simple: “I did it for you, Anna.” She did not act on principle; she acted out of grief. Mangione, in contrast, has never claimed to be acting for anyone at all.

As an Ivy League graduate from a wealthy Baltimore family, he was neither disenfranchised nor a victim of corporate exploitation. He had no terminally ill mother — he wasn’t even insured under UnitedHealthcare. In his confirmed manifesto, Mangione calls his plan “fairly trivial,” justifies it with a plain “these parasites simply had it coming,” and cites vague statistics about healthcare costs without ever claiming to fight for, or even acknowledging, victims of medical exploitation. This is not the language of someone compelled by desperation; it is the language of someone choosing violence as a statement. There is no mention of seeking justice for healthcare victims, no clear beneficiaries of his violence — only revenge.

Mangione’s choice to act refuses to be neatly pigeonholed. His privilege and lack of personal connection complicates attempts to frame him as a righteous avenger, yet the sheer scale of harm he sought to retaliate against makes his motives difficult to dismiss — especially amid the viral media storm that has framed him a martyr rather than a killer.

This shift in public sentiment forces us to reconsider what justice truly means. Mangione’s actions are neither as morally clear-cut as the media portrays nor without historical precedent. Time and time again, history has taken acts of political violence and retrospectively reframed them as justice — often with a cautionary undertone. Leaders of oppressive regimes have been assassinated in the name of preventing future harm, justified as necessary vigilantism. John Brown, who led violent raids against pro-slavery forces in the 19th century, was initially condemned but later rebranded as a hero of justice, one of the many to undergo this transformation. Yet, if history complicates our understanding of such acts, it also serves as a warning.

Even if one accepts the premise that systemic harm constitutes violence, vigilante violence provides no real solution. If every individual were to act as judge, jury, and executioner, society would dissolve into chaos. Killing a CEO doesn’t end corporate greed, assassinating a dictator doesn’t free a nation, and murdering a criminal doesn’t eliminate crime. Rather, extrajudicial retribution creates power vacuums, further suffering, and unintended consequences that spiral out of control.

Individual retribution rarely dismantles the systems it seeks to destroy. The targeted murder of an individual CEO, as in the case of Mangione, does not succeed in undoing the decades of corporate exploitation it critiques or provide a blueprint for a better world. All it leaves behind is a spectacle — one that can be mythologized or condemned but rarely leads to meaningful structural change.

The question of whether Mangione’s actions were an act of misguided ideology or a grim inevitability in a broken system has no easy answer. Perhaps the greater concern, then, is not whether his actions were justified, but rather that so many found them compelling in the first place. Change is afoot. If disillusionment with the system continues to curdle into support for retributive violence, what seems like an outlier today may become a pattern tomorrow.

Dea Skrami • Feb 23, 2025 at 12:09 pm

Too much complaining leads to delirium. This article illustrates my statement.

You use the word alleged in the beginning but throughout the middle and in the end you tag the murder to Luigi Mangione. Better coherence next time.

Then, are you really calling out the ways slavery was fought and abolished by Black people? So, white people could kill, abuse, exploit, lynch black people but the latter had to endure and wander around asking for justice? Furthermore, this case and the focus point of your article lack correlation.

Where is the ‘Conclusions and Recommendations’ paragraph in your article? I would had liked to hear your proposals and suggestions on how to fight corporate greed and social injustice.

Mario • Feb 11, 2025 at 10:54 pm

Free Luigi. Brian Thompson killed thousands.

Luigi II • Feb 9, 2025 at 5:01 am

The common good.

R • Feb 5, 2025 at 9:19 pm

So people facing oppression are the only ones who are justified in fighting back against the oppressors? What about those who were anti-slavery during the Civil War; do you think they had no business fighting unless they were enslaved themselves? We will never achieve class consciousness unless we stop fighting amongst ourselves, and I think empathy and action from those with more privilege is something very positive.

John • Feb 5, 2025 at 4:05 pm

Lol bad take, you don’t need to be directly impacted by something to act. If its broke its broke. What he did wasn’t solve anything it was catalyst— more symbolic for people to wake up

The issue isn’t that people condone murder, its just people dont GAF about a billionaire getting merc’d. Prayers to his family but what did he do besides make billions off people’s suffering?

bRYAN • Feb 5, 2025 at 1:49 am

Couldn’t have said it better, killing the CEO did what? NOTHING, so what did he do? Took a life for no reason. Health system bad we get it, killing makes it better how?

Sharie • Feb 4, 2025 at 2:06 pm

All these articles are the same. They confirm Luigi’s points that the health care system is broken but offer zero solutions. He (Luigi) is correct it’s not awareness at this point but power games at play . People have been advocating for better healthcare and frankly nothing changes.

Pam adams • Feb 4, 2025 at 4:05 am

Mangioni is the spark Americans needed to light the fire to bring about change. Its time to put an end to corporate greed and putting profit over people. Mangioni will go down in history as the peopmes hero!

Da • Feb 4, 2025 at 4:04 am

This guy had no history of violence. I never hear about how his behaviors 6 months to a year before were off and not typical for him. Does he have a psychiatric illness not because he killed but because this change in behavior.

Sara • Feb 4, 2025 at 3:37 am

Not trying to be rude, but like Ryan commented, this article is a waste of time. To argue vigilante justice is excusable but only when the perpetrator has been personally harmed is bizarre. You, I, and most others can’t imagine taking such action ourselves. There are however a rare few willing to sacrifice for the common good despite not being directly affected, and the rest of us judge them from behind a veil of our own limitations. Like Henry David Thoreau wrote about John Brown: “Many, no doubt, are well disposed, but sluggish by constitution and by habit, and they cannot conceive of a man who is actuated by higher motives than they are.”

Sam • Feb 4, 2025 at 3:15 am

Yes they should, this is just propaganda trying to saved corrupt companies. Killing millions of people indirectly is fine, but avenging your mom who died due to united health care denying her claim is so called bad?

Corbin • Feb 3, 2025 at 9:40 pm

You do realize he hasn’t been convicted of any charges, right?

Person • Feb 3, 2025 at 7:14 pm

Free Luigi!

Alan K. • Feb 7, 2025 at 10:16 am

It’s discouraging to see the pro Luigi voices screaming the loudest.

If you Google F___ Luigi Mangione Reddit, you’ll find there’s a community of sane and decent people celebrating the life of Brian Thompson.

Neely • Feb 3, 2025 at 4:54 pm

Too long; didn’t read. Shut the fuck up. #freeluigi

Ryan • Feb 3, 2025 at 1:57 pm

I REALLY appreciate (sarcasm) how you etch the notion that Mangiones actions do not spark change, yet you appear to agree that the system is crooked and offer no alleviating factors to that aborrent truth which really LIMITS your point of view. So thank you so much for a half a$$ed article that does not demenstrate a real, practical solution to the grievances us Americans share with the disgusting, greedy and crooked insurance industry. Your writing is a huge waste of a read. Please, assemble your writing critiques in a more proactive way because this does not help anyone, PERIOD.

Em • Feb 3, 2025 at 11:16 pm

Free Luigi !! Enough said !! We as a nation are hurting with this greed

Ann • Feb 8, 2025 at 12:57 am

You can’t expect a uni writer who has never worked in the health industry to offer a solution to a very complicated problem. One thing she is right about, murder is not going to lead to structural change.

Ted Lasso • Feb 3, 2025 at 1:30 pm

To quote Mangione, in response to this article, “it is extremely out of touch and an insult to the intelligence of the American people and their lived experience.” First off, this whole thing was written without presuming his innocence…that manipulation aside, to say he hasn’t claimed to act for anyone- has he been given an opportunity to speak? How can you know his motives? Or to say that he wasn’t disenfranchised or a victim of corporate exploitation…to exist in the US in modern times is to be both of those things, regardless of relative privilege. Perhaps it wasn’t revenge so much as a call to action. Many Americans can’t see their own chains and the actions of the shooter, whoever he may be, sparked a conversation in the direction of class consciousness amongst the majority that is long overdue. That is why he’s a hero.

Tyler Ackerman • Feb 3, 2025 at 11:21 am

Free Luigi!

libi luo • Feb 4, 2025 at 6:26 am

Deny, defend, depose. Free Luigi!

Bob • Feb 3, 2025 at 11:18 am

Yes they should.