Asian Elephant Habitats in Decline Due to Centuries of Destructive Land Use Practices

Photo by Alexander Olsen/ UCSD Guardian

May 14, 2023

A recent study led by UC San Diego researchers in collaboration with researchers both nationally and internationally found that 64% of elephant habitats in Asia are no longer suitable as a result of several centuries of destructive land-use practices.

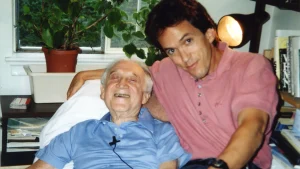

Specifically, the study found that the major driver of habitat loss for elephants and other wildlife in Asia was European colonization in the 17th and 18th centuries, which turned these habitats into large-scale commodity plantations. This is not solely a recent phenomenon, as lead author of the study, UCSD ecology, behavior, and evolution assistant professor, and founder of the nonprofit Trunks & Leaves, Shermin de Silva explained.

“It’s the takeover of countries that enabled things to happen at such scale,” de Silva said. “You have foreign powers come over, taking over the governance [and] ownership of the land from people. And that happens predominantly in Asia.”

Consequently, local habitats were transformed into sizable plantations for commodity export during the colonial era, which has had lasting impacts on the way land is used in the present day.

“Habitats are being converted today pretty much as a continuation of a long-term process,” de Silva explained. “The initial land-use changes happened … when we had, basically, the conversion of lots of natural ecosystems into plantations and export-commodity crops.”

Although the Asian nations studied are no longer ruled by colonial governments, perspectives of land and land-use practices persist. Land is often seen as a site for commodification, such as agriculture, logging, timber extraction, and resource extraction.

“The paradigms that were put in place at that time of how lands should be managed [are still in place],” de Silva said. “Even if you now have local government and local governance, they still use the same value systems that were imposed at that time. So we have the same thing continuing, just by different people.”

During the colonial period, there was more land and more animals compared to humans, but this dynamic has switched, co-author of the study and Colby College environmental studies professor Philip Nyhus explained. Now there are more humans, fewer animals, and less land. This shift, along with the continuation of colonial ideologies about land transformation within colonized nations, led to the expansion of agriculture to sustain the growing local populations. It also led to an increase in infrastructure development.

“If you stretch back over centuries, we’ve gained billions of people on this planet, in particular in Asia, and all of those people need land and to be fed,” Nyhus said. “We’ve also increased the extent of our cities, our towns, our road networks. … We have a lot more areas dominated for the needs of people … and a lot less habitat available for wild animals, including elephants.”

As natural habitats for elephants have dwindled, de Silva emphasized that this growth in population and the consequent expansion of agricultural land use does not mean local populations are to blame. Colonialism has led to a decrease in land available for less disruptive, small-use purposes.

“Our population density has gone up, that’s true, but the amount of wilderness, forest, grassland, whatever else they relied on before, those ecosystems have shrunk,” she said. “It wasn’t their fault that it shrank. They’re just trying to make a living on the space that’s left. That’s a dynamic that I think is not often talked about.”

Local populations are often blamed for habitat loss, de Silva said. Rather, she continues, colonialism is the culprit for a majority of that loss. To evidence this, she explained that local populations had led their lives in those areas for millennia before the arrival of colonizers.

“You see a lot blamed on local people,” de Silva said. “But they’ve always been there; they’ve been there for thousands of years. Why is it that they’re being blamed for destroying habitats today?”

Though Nyhus and his colleagues worked on Geographic Information Systems software to generate models of how the landscape may have looked in the past, because the ecosystems have been so dramatically altered by colonial destruction, de Silva explained, they are unable to fully grasp how they could have looked millennia prior.

“It’s impossible to even visualize what would have been there in the past,” de Silva said.

Still, the study allowed the researchers to consider the history of different landscapes and how both humans and animals have used them, Nyhus explained. This means they can extrapolate their findings to broader applications, like the impact that climate change may have on local ecosystems.

“If we are going to start looking at climate change and how these elephant landscapes might look in the future, understanding how they look today is an important step,” he said.

de Silva further explained that one reason for starting the study was to conjure long-term perspectives on the environment and to use their findings for future conservation efforts. They specifically chose to study elephants because of the many different ecosystems they are found living in. Thus, the study supplies a general overview of the environment, a comparison of different kinds of environments, and a historical understanding of what led environments to look the way they do today. This knowledge, she felt, is important because it allows scientists to better engage with effective conservation practices.

“It’s important in recognizing the challenges that we face today … to better understand the history of how we got there because otherwise, our efforts to conserve or restore ecosystems might be misguided,” de Silva said. “We might be aiming toward the wrong targets, like, for example, excluding people who [have] always managed those environments. They might, in fact, be an important critical part of maintaining environments.”

Editor’s Note: On 6/6/23 at 4:36pm we updated the name of Shermin de Silva to be correctly spelled.