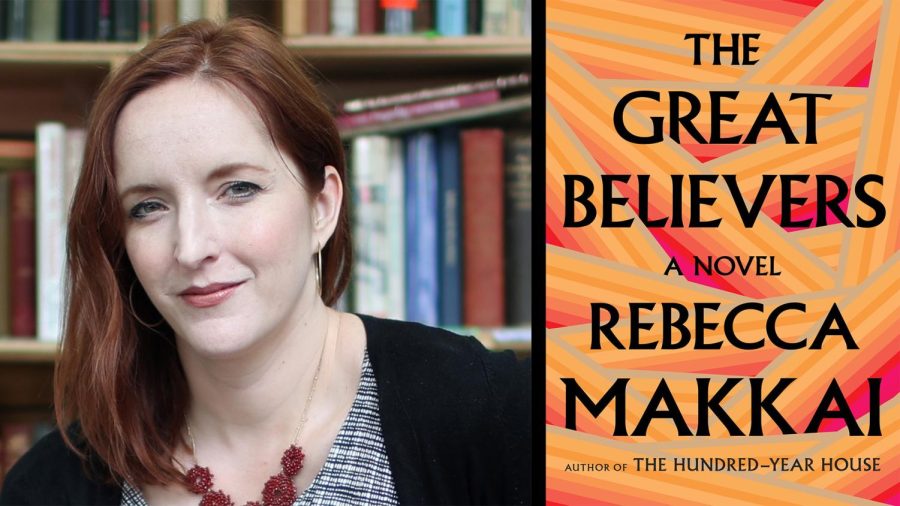

Novel Review: “The Great Believers”

Rebecca Makkai’s “The Great Believers” is an astonishingly hopeful novel despite the tremendous and constant loss circling its characters. The work tugs on the strings of mortality and is a testament to how we chose to play them.

May 7, 2023

Told between altering perspectives across different time periods, “The Great Believers” began with the intention of honoring the Paris art scene in the period between the two World Wars. Rebecca Makkai began with the creation of Yale Tishman, a gay museum developer on the cusp of obtaining an incredible collection from the current age of 1980s Chicago. But knee-deep in the creation of Yale’s character, his circle, and circumstance, the lens transcended beyond its initial focal point and shifted towards the AIDS epidemic coursing through the streets of the Windy City. Makkai used her hometown as the center point for this crisis because, despite being the third largest city in the country, historical documentation of the epidemic appears to be slimmer than it should be. Makkai, holed up in the Harold Washington Library of Downtown Chicago, began her research, interviewing countless people who lived to share their experiences.

Yale was both the product and inspiration of Makkai’s intense research and dedication, so much so that she sometimes forgets that he is fiction and feels the urge to confide in him or share good news. Makkai notes that thinking of Yale as a real person was necessary for her process, ultimately making it easy to get attached to the character. When readers are introduced to Yale, he is in a long-term monogamous relationship, at the brink of catapulting his career, and has freshly lost one of his closest friends, Nico, to AIDS. Part of Yale’s appeal is that he manages to remain simultaneously grounded and expressive. He’s introspective, which seems to be the synthesis of these concepts: to be acutely aware of one’s own emotions, to feel them and acknowledge them, but prevent them from being the sole basis and justification for one’s actions. Readers discover these attributes in real-time as he meticulously arrives at each feeling and decision. At times, his delicacy can be frustrating; we want him to lash out against the horrors circling around him and enclosing him, to be able to experience some form of catharsis. But Makkai does not truly give this to the audience, not in a raw, blinding action that is truly desired. Potentially it is a fault of his character, to reduce everything down its parts instead of simply feeling them. I think it’s incredibly human to think we need to be paralyzingly rational about everything, and loosening these chains is a struggle many face throughout their lives.

Yale’s most standout characteristic, one noticed repeatedly by other characters, is that he is kind. He is not a typically dominating force, but his compassion holds a sense of magnetism that draws those willing to look. It’s why some take advantage of him, but also why he is loved so deeply. During a time of so much anguish and death, compassion remains a constant. When he loses and loses, he clings to the fabric of his identity and finds himself embraced by it. I believe that kindness and hopefulness are intertwined, and that cynicism is a facet of anger. An air of hopefulness is persistent throughout the novel because of its kindhearted focal points. Yale is by no means a saint, and borders on a morally gray line at times, but it is always clear where his heart lies. When you can be kind, you can be hopeful in the direst circumstances. Fiona, Nico’s younger sister, finds comfort in Yale. As both of them are thrown into rapid and horrific changes, they manage to cling to each other. And years down the line, in 2015, Fiona begins the search for her estranged daughter in Paris which becomes the alternate perspective that the novel bounces between.

In referring to the loss of her brother to AIDS and so many of her friends, Yale tells Fiona that she has survived a war. It is one of the many ways in which Makkai is able to draw parallels between the Lost Generation and the survivors of the AIDS epidemic. To watch the slow, agonizing death of so many loved ones induces trauma so few can understand. Surviving this “war” turns out to make an already stubborn Fiona even more thick-headed. She’s unafraid to cause a scene or call people out if it means the preservation or security of her loved ones. Much of her character feels like a foil to Yale; she tends to be more reactionary or impulsive and unafraid to make her intentions clear. However, Fiona finds fulfillment and maturity in balancing her instincts with introspective moments. And similarly, Yale finds joy in releasing his reigns and letting emotion drive him. It’s not so much that you have to lead by reason or emotion, but rather be willing to step out of the mental construction of yourself in order to grow.

While growth remains persistent, the catalysts of the novel are tragedies. Makkai is unafraid to go into the grotesque nature of AIDS and the honest deterioration of the body without appearing to revel in it. She escapes falling victim to trauma porn by giving stark and necessary depictions without embellishing for the sake of exasperating one’s condition. Even aside from the disease, Fiona’s tragic relationship with her daughter is not prodded like an unripe scab, but is described because it serves as the foundation for eventual healing. Hope, again, remains because tragedies do not become all-encompassing, but ways that help us re-evaluate what life means for us.

“The Great Believers” is an incredible read. It is well-paced, educational, and honest. The characters are dynamic and engaging, Makkai’s writing style flows smoothly, and the story will sit with you for a while to come. Even though Makkai sometimes forgets that her characters are not real, the eventual hope amidst tragedy seems to float off of the pages and solidify into the real world.

Grade: A

Released: June 2018

Image courtesy of The Chicago Tribune