A Life of Beauty and Bloodshed

Mar 12, 2023

In her debut article, contributing writer Arshia Singh details how the life of Nan Goldin, captured by Oscar-winner Laura Poitras in “All the Beauty and Bloodshed,” allowed her to see the power that results when art and activism become one.

We have certain preconceptions of what it means to be an artist: someone willing to challenge the status quo, be fully and authentically themselves, and have pride in what they can and will continue to achieve. We see this in Nan Goldin, but she is more than an artist. She is strength, she is passion, and she is every insurmountable force one could imagine. Prior to watching this film, I had only heard Goldin’s name a handful of times and was not nearly prepared for the unbelievable woman I was about to discover. There is incredible power in art and in activism, and one could not exist without the other.

A documentary directed by Oscar-winner Laura Poitras, “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” tackles the narrative of Nan Goldin’s life, interweaving her contributions to the art world with her work against Big Pharma amidst the opioid crisis. Its main focus is Goldin’s experience with an addiction to OxyContin and how she not only overcame it but sought out justice for those also affected by addiction around the world using her greatest asset: her voice.

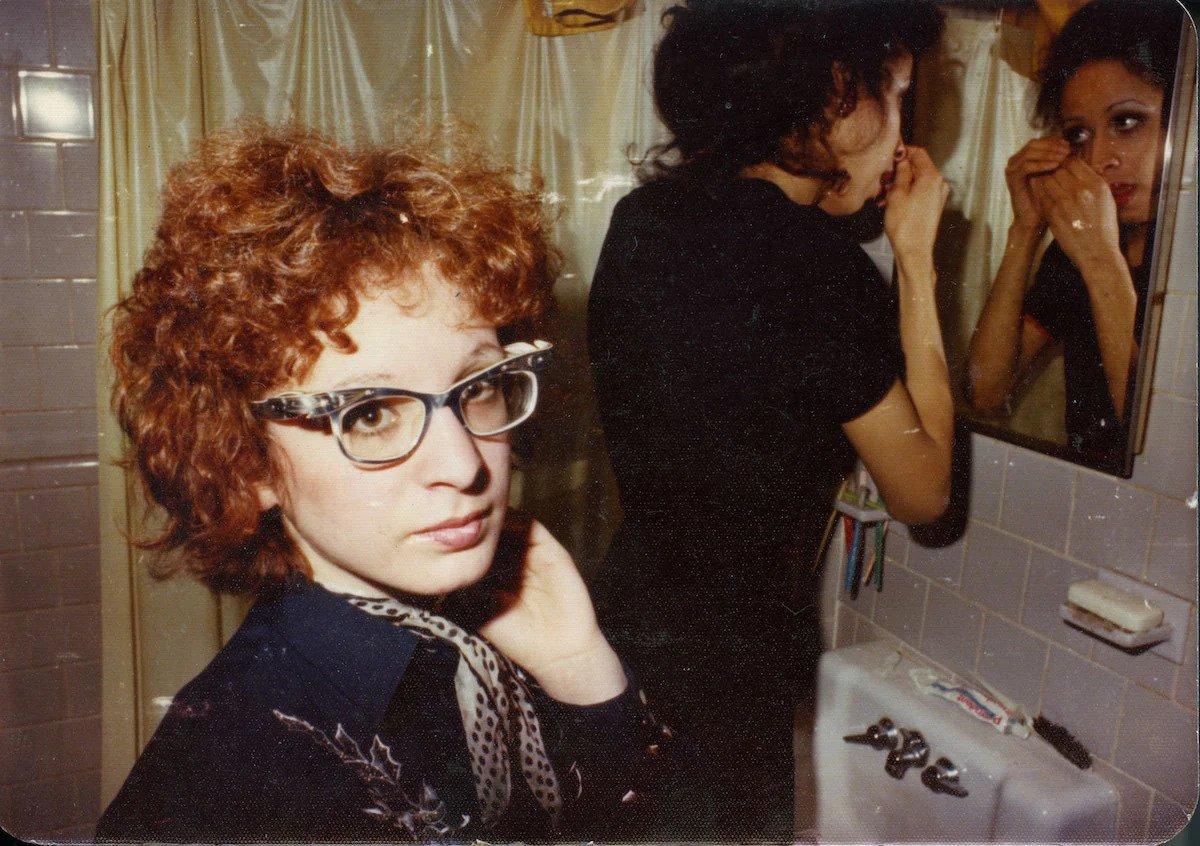

Goldin’s story is told alongside a slideshow of photos that reflect her youth as she narrates the memories attached to those moments. Some are darker than others, like the loss of her sister at a young age and her battle with opioid addiction; some are ever glorious, like her journey to meeting people who accepted her and whom she saw for their true selves. Goldin used photography when she found herself unable to speak, and therefore, her camera did all the talking. As the documentary progresses, it weaves in more present-day footage of Goldin’s efforts to combat the opioid crisis with her organization. We see her grow and face challenges of her own while simultaneously persevering to survive.

Throughout her late teens and well into her twenties, Goldin befriended artists of every style — actors, filmmakers, photographers, drag queens, and all innovators alike. She had the ability to capture them all in a way that accentuated their natural beauty, effortlessly transcendent and timelessly decadent. Goldin’s view encompassed a scope beyond the norm, and her talent was evident through the simplicity with which she crafted her work. She very tangibly knew her place in society; she says, “There is a misunderstanding that my work is about marginalized people. But we were never marginalized, because we were the world.” Exploring the beauty of “radicals” and of people searching for a sense of liberation; that is what art meant to Goldin.

As the documentary delves deeper into the narrative of her past and her odyssey into the art world, more recent events are highlighted in Goldin’s efforts with the organization she founded, P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). Their primary goal is to take down the Sackler name, a family of great wealth resulting from the ownership of pharmaceutical companies. One of them, Purdue Pharma, was proven to be responsible for the production of OxyContin, a harmful drug that was marketed to doctors as not as addictive as it actually was. The Sacklers have ties to many large institutions, including museums such as the MET and the Louvre and universities like Harvard.

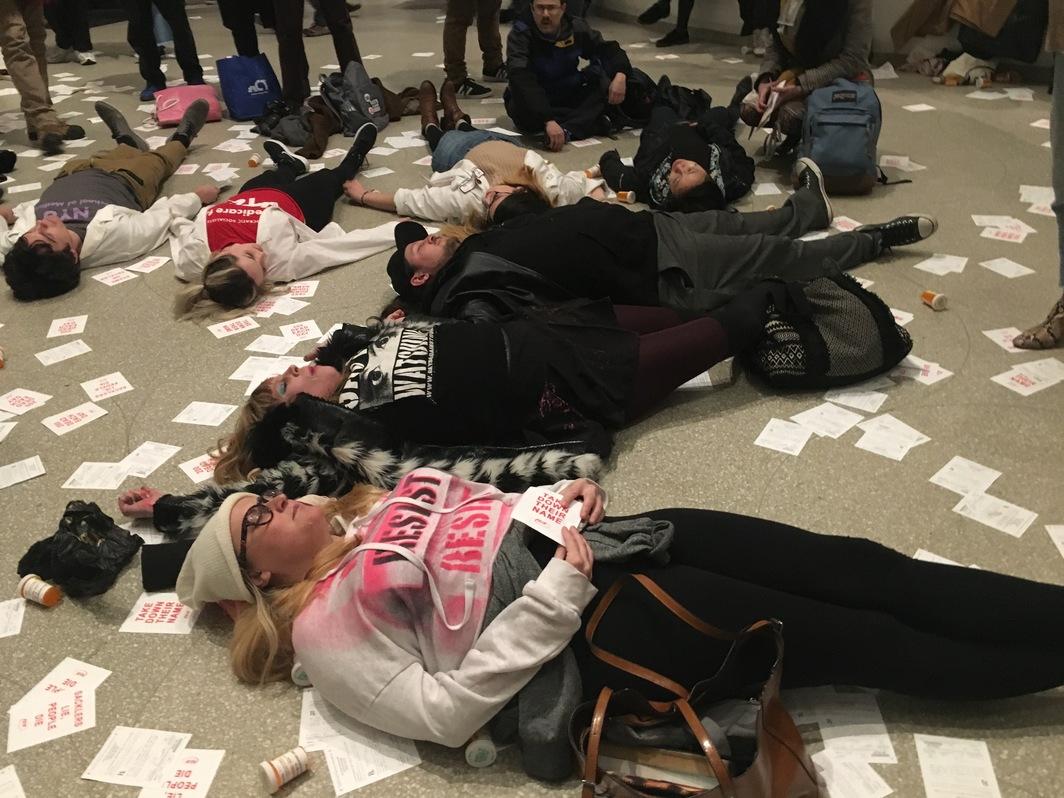

Goldin’s experience begins with her addiction to OxyContin, which began when she was prescribed the drug after a surgery. She suffered great challenges in overcoming her addiction, including an overdose from which she grimly and solely recovered. Goldin craved justice for the hundreds of thousands of lives lost to and affected by opioid overdose and demanded retributions from the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma. As a team, P.A.I.N. organized protests and participated in public demonstrations that illustrated the corruption that was governing these industrial titans, and insisted they reallocate their funds toward treatment for opioid addiction.

Not only was her organization a means of activism, but her art was equally important to the cause and to culture. Art, anything created for a purpose to be seen, holds greater power than other mediums. Along with drug reform, Goldin did impactful work regarding the AIDS epidemic and LGBTQ health, such as setting up galleries to showcase her and other artists’ work on the subject. Friends and colleagues alike stood with Goldin for change, striving to create a better world for the people most affected. Wealthy corporations merely watched from the sidelines as they fell complicit in abetting the growing drug-related death count in this country.

In 2020, after four long years and with great effort, P.A.I.N. succeeded in its mission. Many large museums and institutions removed the Sackler name from their brands, refusing the family’s donations and funding. This was a monumental moment not only for P.A.I.N. and Goldin but for every individual burdened with the pain of knowing the brutality of opioid addiction. It was a win for the people: the ones who got out, the ones doing anything to get by, and the ones whose true home was on the other side.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” accomplishes relaying a narrative unlike anything I’ve seen, and we as viewers are left to ponder our own power in the world.

Create with devotion; lead with intention. Art is activism.

Images courtesy of The Financial Times, ARTnews.com, AnOther Magazine, Artspace, and Artforum

Poonam • Mar 14, 2023 at 7:08 pm

Congratulations on your debut with such a powerful story, truely inspiring !

keep the juices flowing ! 🙂