I stare, perplexed and amazed. Her skin is clear and poreless, her forehead and hairline both perfectly symmetrical to the rest of her face. Her full lips are artificially enhanced — but not so much that they appear fake, or plastic. Her eyebrows are thinner and more arched, the eyes more slanted, and their normal deep brown tinted with gorgeous honey highlights. Her nose is slim and feminine, almost delicately proportional. In sum, the woman is beautiful yet unfamiliar — “is that me?” I think to myself for the first time that a selfie turned out better than my reflection in the mirror. But as I continue to stare at the selfie I took with an Instagram filter, I grow more and more uncomfortable with the subtle enhancements done to my face. I take a selfie without any filters and flip back and forth between the two pictures, trying to reassure myself that the heavy feeling in my stomach is an overreaction. It’s possible that I’m actually just as gorgeous as the Instagram baddies, right?

I am well-aware of how toxic social media is; I did a whole research paper on its addictive qualities when I was in community college. During quarantine, I made sure to limit my time on the most popular social media platforms for the sake of maintaining my mental health and keeping up my grades. However, it appeared I had missed one negative impact that social media has in my research report —the hit to self-esteem that filters, especially Instagram filters, have on people, specifically women and girls. Unsurprisingly enough, it is highly possible that Instagram knew of the negative impact that it had on the self-image of young women and girls. There is evidence to suggest that Instagram knew about the negative correlation between body image and Instagram consumption. Rest assured to the women and girls out there struggling with your self-esteem as I was when I first came into contact with similar filters on Snapchat — you are not alone. An intentionally toxic byproduct of you selling your attention to these social media companies is the festering feeling of loneliness and depression that push you to partake in the destruction of your body image even more.

For me personally, I struggled especially with my “Facetuned” selfie because I also couldn’t recognize the race of the person in the camera anymore. Being a Somali woman living in a nearly all-white suburb and going to a majority white school, most people cannot identify what race I am, let alone where Somalia is on a map. Unfortunately, I was still exposed to anti-Blackness while growing up, even though I was never around Black people. I internalized this anti-Blackness and as I learned to live around almost all white people, I sometimes accepted it as a compliment that someone thought I was Moroccan, or that a South Asian person mistook me for Indian. My sparse experiences with Islamophobia also didn’t help, so I generally accepted whichever race the newest white person I met assigned to me. I figured it didn’t matter.

Now that I am an adult, my issues of self-identity and questions of representation have, for the most part, been laid to rest. I take pride in my distinctly East African five-head, my larger-than-white-people nose, my giant brown eyes. But for the first time in several years, the unfamiliar eyes I saw staring back at me on my iPhone also challenged my Somali pride and rendered me speechless. She was beautiful, but she wasn’t me. She looked racially ambiguous in a way that only Instagram models can pull off. The uncomfortable feeling of inadequacy regarding my Somaliniimo was as acute as ever. I contemplated the fact that if I made my account public and posted this selfie on my story, lots of attention from both men and women would be sent my way. I was hyper conscious of the way the Instagram filter had somehow picked up on all of my insecurities and fixed them, as if the algorithm could automatically determine which aspects of the human face “under-performed” relative to all the others. After all, she was more beautiful than who I saw in the mirror. I had indeed achieved the “Insta-baddie” face that I commonly see while scrolling through my For You Page, but at what cost? I had erased my ethnic features and corrupted my self-esteem. Without too much conscious effort on my part, I became the unattainable beauty standard and lost my priceless racial identity.

I deleted both selfies and the Instagram app on my phone and decided that it would be a while before Instagram saw me again. It has been three weeks since that selfie was taken, and those honey brown eyes still stare up at me every time I open up my camera. I wonder how long it will take before they completely disappear from my memory. To all the women and girls out there, I strongly suggest you do the same. I can absolutely say my quarantine was not as bad as it could have been had I decided to return to normally using the app.

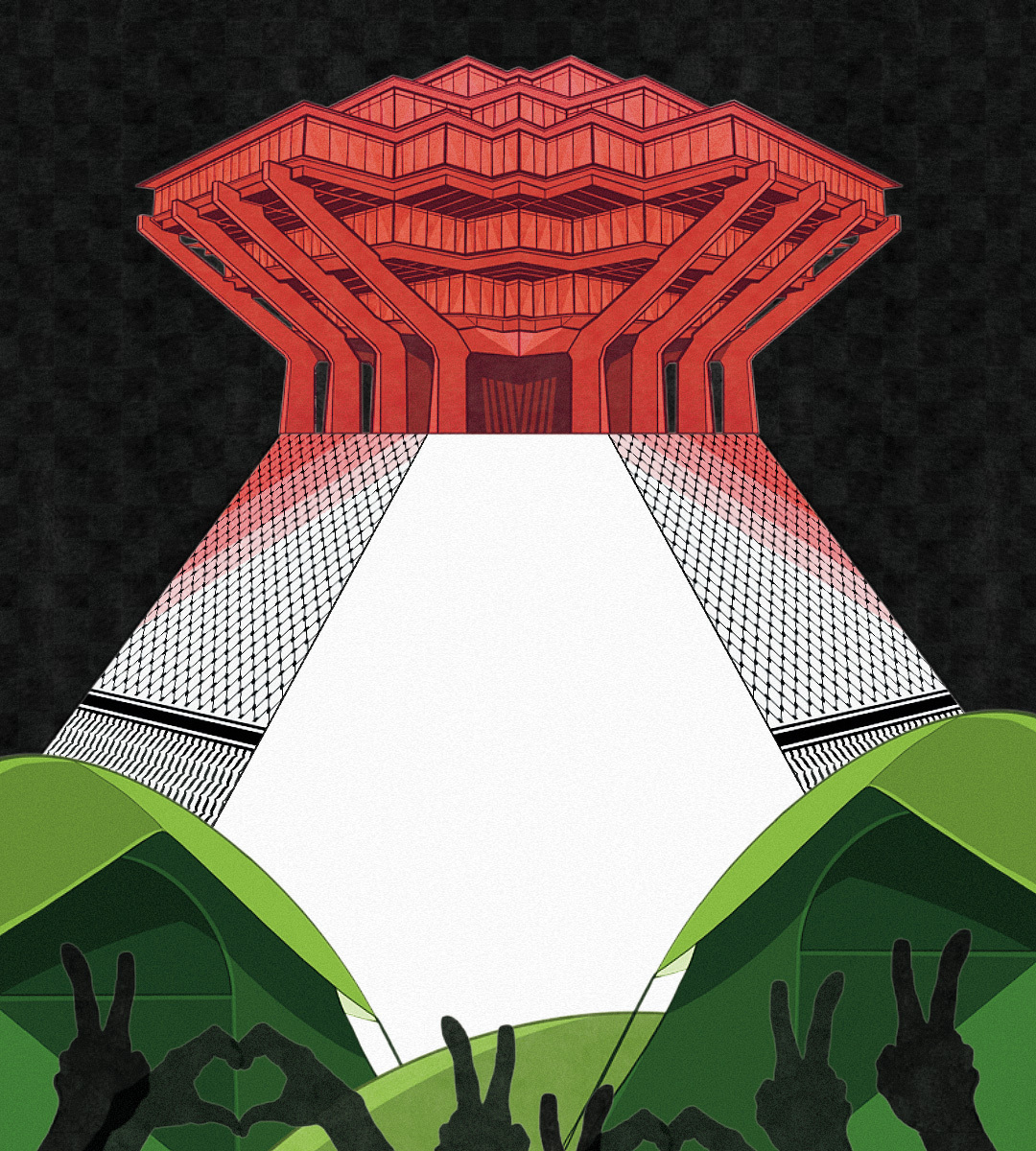

Image courtesy of Saida Hassan, UCSD Guardian Design Editor.

William • Feb 10, 2022 at 2:00 am

https://ucsdguardian.org/2022/02/06/sat-goes-digital/#comment-128569

Tif • Dec 20, 2021 at 7:05 pm

I’m guessing you’ve read a lot of SMM literature. I attempted to comprehend all of IG’s algorithms. It’s impossible to be on top of everything all of the time. Because I have a https://accfarm.com , accfarm assists me with this. I’ll need a good audience to be successful. They assisted me in all of the needed areas.

John Burl Smith • Dec 15, 2021 at 2:41 pm

Of Mice and Men

By John Burl Smith author “The 400th From Slavery to Hip Hop”

The phrase “The best laid schemes of mice and men” is found originally in Robert Burns’ poem “To a Mouse,” written in 1786. The poem is a response to the author’s careless destruction, while plowing, of a mouse’s nest in a field. The resulting poem is Burns’ apology to the mouse. Robert Burns (1/25/1759–7/21/1796) was a Scottish poet and lyricist, universally regarded, as Scotland’s national poet. Burns, a cultural icon, is celebrated as a national charismatic cult leader, during the 19th and 20th centuries and pioneer of the “Romantic Movement.” Posthumously, he became the inspiration of both liberalism and socialism.

On the other hand, John Ernst Steinbeck, Jr. (2/27/1902–12/20/1968) was a very prolific American author (33 books), which makes him a giant of American letters. Winner of the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature, Steinbeck is noted “for his realistic and imaginative writings, while combining sympathetic humor and keen social perception.” One of his iconic works “Of Mice and Men,” published in 1937, is characterized as a detailed and intricate story set during America’s Great Depression, which began in 1929 and lasted into the late 1930s. Steinbeck wrote in various genres, and like Burns, uses the word “mouse” in one of his most significant works “Of Mice and Men.” Unlike Burns in his poem “To a Mouse,” Steinbeck’s mouse story has a different intent. For most readers Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” reflects America’s uncaring and total disregard for human life, as Burns plowman for the home of a rat. Steinbeck’s plot revolves around two nomadic farm workers, Lennie and George. George is a big strong man but mentally challenged, whereas Lennie is intelligent but uneducated, hence Lennie looks after his gentle-giant dimwitted friend.

For me both stories are reflective of Burns immortal line “The best laid schemes of mice and men,” and is a prelude to where America finds itself today, as it struggles to survive the disastrous whirlwind of Donald Trump’s uncaring and destructive presidency. Cosigned in their book, “I Alone Can Fix It Donald J. Trump’s Final Catastrophic Year” Washington Post reporters Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker, brilliantly describes Trumps “best laid plans and how he became a “rat,” with his 1/6 insurrection, which continues to ravish America’s democracy. Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” as “I Alone Can Fix It” details the odious impact and implications for America, as Trump’s stench hoovers over states like Georgia, Arizona and Florida smothering democracy, with Republican voter suppression.

I use “The best laid plans of mice and men,” to segue a mice to a rat, which was revealed by “Tic Tokers,” which pulled the cover off of Trump’s scam, as president and re-election. Deploying a scam of their own they showed out of the gate, the “scammer-in-chief,” “orange hair and all, Tic Tokers convinced Trump, over a million MAGA lovers were headed for Tulsa. With dollar signs for eyeballs, Trump booked up all the hotels, and added overflow space for the giant arena, as well as an outdoor concert for his huge event. However, less than 6,000 MAGA fans showed up, as Tic Tokers punched holes in Trump’s invincibility. My point is kids figured out what grownups are still confused about today, which is “Trump is a RAT.” Moreover, I am convinced 11th and 12th graders and other young voters will be America democracy’s “saving grace!!” They are far smarter than they look and possess the voting power to prove it, while all Republicans have come up with are lies and voter suppression schemes in states like Georgia, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Texas and others.

The fast forward to the present is prompted by last week’s 42nd Harvard Youth Poll (HYP), which showed young Americans are very much aware of the threat Republicans represent to democracy. Young Americans, in this latest survey, shared concerns for repercussions from the pandemic, democratic government, the Biden administration, and climate change among other things. The HYP found young Americans are worried about democracy. Even more striking, 35% of respondents anticipate a second civil war during their lifetimes, where 25% believe that at least one state will secede. More than half feel democracy is under attack, and at least half of all respondents struggled with feelings of hopelessness and depression. Even more alarming, 50% of young people polled said that COVID-19 has changed them, and 51% say the pandemic had a negative impact on their life. While, 51% felt down or depressed at several different instances two weeks before the survey.

Additionally, young people felt strongly affected and worried about the threat of climate change. Significantly, 56% of young Americans expect climate change to have an impact on their future decisions and 45% already see it affecting their local communities. Moreover, large numbers of both Democrats and Republicans believe that individual changes in behavior can have the greatest positive impact addressing the climate change crisis. More than half of respondents believe the U.S. government is not doing enough to address climate change. In addition to addressing climate change, respondents see strengthening the economy, uniting the country, and improving health care as key issues for the Biden administration.

The HYP spoke with 2,109 people 18 and 29 years of age, on various topics from across the country and found a striking lack of confidence in U.S. democracy among young Americans. Only 7% view it as a “healthy democracy,” and 52% believe that “democracy is either in trouble or failing.” Support for Pres. Biden has also dropped across the board since the last Harvard Youth Poll in the spring. A majority of respondents were unhappy with how the president and Congress do their jobs. Among young Democrats, approval for Biden stands at 75%, a drop of 10 points since the last survey in March. Republican approval continues to tank, slumping to 9%—a decrease of 13 points since the spring—while among independents it dropped to 39%, a 14-point decrease. IOP Director Mark Gearan stated, “Our political leaders on both sides of the aisle would benefit tremendously from listening to the concerns that our students and young voters have raised about the challenges facing our democracy and their genuine desire for political parties to stop attacks and find common ground.”

This brings us back to where we began “the best laid schemes of mice and men” and Donald J. Trump face to face with his attempted insurrectionist on 1/6. The US census has been given Americans numbers that show young Americans between the ages of 18 to 29 constitute the largest voting demographic presently in America. Now, for the first time ever, the HYP has established through personal preferences expressed by young voters, older voters can longer force their demands down young voters’ throats. The older generation must finally admit its failure to give young people VOICE, created Donald Trump. Now that older voters are no longer the majority, high school 11th and 12th graders have the voting power at the polls to elect and defeat MAGA with their ballots. Young people no longer must take to the street, as the only way to be heard. This is the threat Republican voter suppression is aimed to stop. Consequently, high school, 11th and 12th graders must do for their rabid MAGA parents and grandparents, as Lennie (Of Mice and Men) did for his gentle-giant dimwitted friend, save them before Trump leads them over a cliff, like lemming or another kind of rodent, as part of his “RAT PACK!!!”