Government entities are investing into research at UC San Diego. With the military entering the fray, scientists face the ethical ramifications of their research eventually being militarized.

Scientific research touches some part of every person’s life. You are reading this article on some screen right now, on a device with that plugs into a wall to “charge.” Science has evolved so rapidly that it would be impossible to explain that last sentence to someone who lived in the 18th century. Even excluding physical innovation, the impact of research pervades our culture, constantly reshaping the knowledge humanity generally regards as proven facts.

Science, for example, has revolutionized how mental health is viewed and treated today in the United States compared to 65 years ago, when people were institutionalized for any hint of neurodivergence.

Due in part to advances in psychology, experts have changed what they categorize as mental illness and helped develop new, more constructive types of therapy. Further understanding of neurology has changed how mental illness is described and treated. Not to mention understanding the physical causes of mental illness has helped reduce the stigma around mental health as a whole.

Without research into chemistry and biology, scientists could not develop safe and effective medications to treat mental illness.

UC San Diego is world-renowned for its scientific research. In 2019, UCSD took in $1.35 billion in research funding. Of that total, $101 million came from the Department of Defense.

This huge influx of resources opens the door for the development of innovations that improve people’s lives. Yet in all the eagerness to push the limits of scientific achievement, questions about the influence of the sponsors of research have gone unanswered.

Charles Thorpe, a professor of the sociology of science and technology at UCSD, provided some insight into the repercussions of increased military funding of scientific research. He drew attention to the practical difficulties in truly parsing out the influences of military spending on research. Authors of press releases about research tend to word the statements in ways that can be difficult for individuals outside the discipline to understand, and often, the practical uses of such research are not clearly stated.

To explain this phenomenon, Thorpe borrowed a term from Jeff Schmidt, a physicist who coined the phrase “social significance concealment game.”

Schmidt used the phrase to evaluate the purpose of the sometimes very technical, but also vague language scientists use to explain their research. Schmidt noted that this strategy was especially utilized by scientists involved in potentially controversial research like weapons development.

They can describe all the minute details of their research in cell imagining and the reader still might not know if they specialize in botany or immunology.

Possibly, scientists are not at liberty to say what they are actually researching, but the unclear nature of their language could also be intentional. With the lack of transparency, abstracts describing projects directly related to the development of weapons will read the same as research into coral life cycles.

“Scientists involved in weapons research conceal from their academic colleagues and students and from the public the actual military nature of that research, giving descriptions of it that sound like it’s basic blue skies academic research, when in fact when you read an account of it by the military agency that funds the research, you see its real social purpose, which is the production of weapons,” Thorpe told the UCSD Guardian.

If the true aim of research is concealed to a certain extent, more context clues can help discern what research has been militarized. One helpful indicator of the true uses of research is who chooses to foot the bill. According to their website, The Department of Defense’s mission is to “provide the military forces needed to deter war and ensure our nation’s security.” Yet, the connection between this aim and all of the research they fund is not always abundantly clear.

For example, a neurobiology research project focusing on cell morphology received a grant in the form of research equipment from the Department of Defense. In a bulletin from UCSD, Shelley Halpain, a professor of neurobiology, was celebrated as a recipient of a (DURIP) award from the Department of Defense.

“She and her colleagues are using advanced fluorescence microscopy to measure energy demand within single synapses, which are less than one femtoliter (500 times smaller than a single grain of salt) in volume,” UCSD wrote in the bulletin. “Their findings may help inform the design of efficient, bio-inspired information processing systems.”

The description provided by UCSD relayed few specifics or details that would relay the applications of this research. This could be an example of the “social significance concealment game” at work. There are details given about the method of study, fluorescence microscopy, and how refined the procedure is, but what could be meant by “bio-inspired information processing systems” is not clarified.

The person best suited to interpret this announcement is one of the principal researchers. Halpain explained that her research seeks to understand neuroplasticity: the brain’s ability to modify, change, and adapt both structure and function. While the real world impact of her research is not clearly stated in the description above, the positive effects it could have on individuals’ lives is profound.

“Understanding what causes neurons’ synapses to form and what causes them to become destabilized is very fundamental to lots of brain diseases and it’s not just limited to the degenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, but there’s you know more and more evidence that that synapse perturbations are also fundamental to mental disorders like autism and to psychiatric disorders like bipolar disorder,” Halpain told the Guardian.

For individuals who need better treatment options for their bipolar disorder or whose cognition continues to rapidly deteriorate as a result of their Alzhimer’s, there may be no cost that could outweigh the benefit of this research. But for those of us who are not currently impacted by this research, the potential for it’s weaponization might be a more pressing concern.

Halpain could only speculate on why the military might be interested in this particular research.

“So they [the DOD] expressed an interest in understanding how nervous systems, how it is that nervous systems are able to use their very limited energy supplies in an efficient way to store vast amounts of information,” Haplin said. “Now, why might the military be interested in this question? Well, I am not an expert. I don’t really do, like, you know, weapons research or, you know, that type of stuff, but you can imagine that a lot of advances in technology require that computer systems operate extremely efficiently and you can make computers more powerful and, and tinier.”

This neurobiology research, along with its potential medical uses, could aid the Department of Defense in creating more sophisticated technology modeled after biology. But has the Department of Defense’s involvement in this research influenced its goals or approach? Fortunately, checks and balances are in place to prevent research aims from being moved in a certain direction due to pressure from the organization funding them.

At UCSD, there is an entire office for addressing conflicts of interest with the goal of maintaining research integrity. That way, for example, any entity with a vested interest in certain research producing a targeted outcome would be barred from directly influencing scientific procedures.

Additionally, there are strict guidelines for the manner in which funding is awarded and the parameters for both the organization providing capital and the research group. Halpain shed some light on this complicated and somewhat rigid system.

“A grant application can be structured to be, like, we’re partnering with you in this research, or they can be structured as we want to give you the money, we’re not going to have any influence whatsoever in your research, right, and that’s those sort of things have to be clear,” Haplin said.“I think these days, ethical rules are very well spelled out.”

Potentially, instead of pressure being applied throughout research and development to generate a particular outcome, influence may be exerted in terms of who gets funding in the first place, which could account for why, in her experience, Halpain hasn’t observed the goals of a project being restructured over the course of development.

The Department of Defense allocates more of their research and development funds to technology, defensive health, and applied research sectors rather than basic research. Basic research seeks to expand knowledge in general and “does not have immediate commercial objectives.” With this allocation as an expression of its priorities, the Department of Defense might be more likely to fund a project if they see utility in it.

While Halpain argued there exists enough separation between benefactor and researcher, there are instances in the past where the motivation to receive funding has shifted the proposal of research projects.

Vera Kistiakowsky, previously a physicist professor at MIT, found that certain projects realigned their interests in order to serve one of the Department of Defense’s areas of interest..

“Interested researchers typically will [contact DoD program managers … These interactions will help potential proposers to decide whether their ideas coincide with DoD research needs,” Vera Kistiakowsky found in her study. “In instances where ideas do not initially fit DoD programs, the potential proposer may, with information provided by a research administrator modify his or her approach to accommodate DoD needs.”

It is a mutually beneficial situation; the project receives funding and the DoD gains innovation.

But, the sponsor-researcher dynamic opens the door for a potential conflict between what the student body believes is morally permissible and the real-world impact our research has.

The Jacob’s School of Engineering currently partners with those in the arms industry — including Raytheon Technologies and BAE Systems.

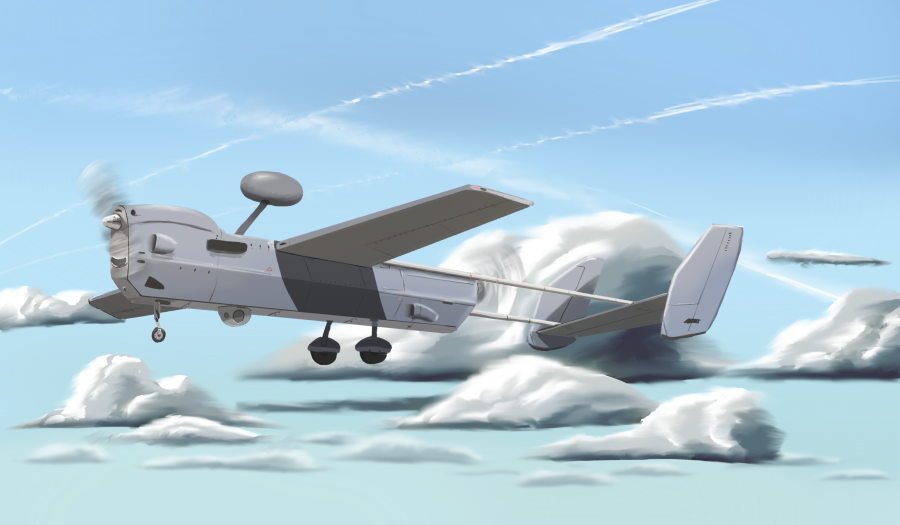

One of these past partnerships involved the Jacob’s School department of structural engineering working with Northrop Grumman, a defense contractor, to create the Hunter MQ-5B drone.

The drone that became the Hunter MQ-5b started out as a reconnaissance drone, primarily focused on information collection and suited for operations like search and rescue. The Jacob’s School of Engineering helped turn it into a more efficient weapon.

“The Jacob’s School research here was aimed at increasing the payload – the amount of weight of a drone could carry,” Thorpe told the Guardian. “So part of that research facilitated transforming that drone from a reconnaissance drone into a lethal arms drone that could carry laser-guided munitions.”

How Northrop Grumman spoke of the ultimate outcome of this project confirms this.

“The increased takeoff weight gives the U.S. Army the flexibility to add additional communications, intelligence and weapon payloads to the Hunter, expanding the capabilities of the warfighter,” a lead engineer from the project representing Northrop Grumman said in a statement. “This flexibility will expand the aircraft’s multi-mission role on the battlefield.”

The Jacob’s School of Engineering, through this partnership, enabled this drone to carry additional weight, making it better equipped for war. That research has come to fruition: “The US Army’s first lethal use of an armed drone was in Iraq in September 2007, when a Hunter MQ-5B dropped a Northrop Grumman laser-guided Viper Strike munition.”

Defendants of drone warfare argue that their ability to reduce human error ensures fewer civilian casualties and their use distances soldiers from conflict which reduces the loss of life to American troops. While the use of drones is continually debated, UCSD was directly involved in developing one, the Hunter MQ-5B, that was put to use.

The Department of Defense is not the only government branch that contributes to militarized research. The Department of Energy oversees nuclear weapons development; there is a lot of overlap between what is necessary to build a nuclear power plant and a nuclear bomb.

Not even the Department of Agriculture can be underestimated. According to a study by Reeves and Voenky, biological weapons research might have been conducted under the guise of agricultural genetic technology research.

No field of science is above investigation. Just like in biological research, breakthroughs in chemistry could inform the refinement of chemical weapons.

Another complication is that the line between defensive and offensive research is sometimes blurred. A lot of the knowledge that would be needed to create a more efficient and deadly chemical or biological weapon is the same as would be needed to create a more effective anetidote to the same weapons.

For example, botulinum toxin is one of the most lethal toxins in the world and therefore is a very likely agent to be used in biological warfare. But researching how to better treat botulism could also shed light on how to make more potent botulinum toxin.

These potential consequences of scientific research are complex. For one, research that has genuine humanitarian uses can be harnessed by military agencies to make weapons. On top of that, funding that pours in from these military-oriented agencies and companies may be shifting the focus of research — either directly by repositioning goals or indirectly by simply being selective about the projects that get funding.

That being said, the benefits are self-evident. Without scientific research, people would simply die if they stepped on a rusty nail and would not be able to fly home to visit their families for Thanksgiving. There would be no Roombas roaming or politicians tweeting. Without the green revolution, most of us would have starved to death 30 years ago.

For the scientific knowledge on the brink of discovery today, the investment from these agencies is undoubtedly crucial. Halpain explained that funding from the government, not excluding the Department of Defense, makes a lot of her research possible. Individuals or firms just don’t have the same capacity to take on the risk of investing in projects that could hit dead ends nor do they have the sheer volume of capital that the government does.

Still, Thorpe argued that we have lost more innovations as a result of this funneling of research than we have gained.

“Military funding of science diverts science into narrowly militaristic purposes when it should be going into other spheres” Thorpe said.

The state of scientific research is left in a position without an obvious choice. The money that government agencies like the Department of Defense provide allows scientists to discover new phenomena, which can have humanitarian and consumeristic value. The Department of Defense, however, will use some of those discoveries to further advance the military and perpetuate violence.

Art by Andrew Diep for the UC San Diego Guardian.

Alice • Mar 3, 2021 at 4:57 am

This solution has become widely popular not just because of the novelty of the approach. It’s all about the rapid growth of various types of attacks, which over and over again become more sophisticated, learn more about CenturyLink