An analysis on the topic of reclaiming symbols of hate and who should be allowed to do so.

“No offense.” We hear this phrase all the time, but is it really for the speaker to decide whether a sentence is offensive or not? It is the offended who should be tasked to decide whether the comment is menial enough to let slide.

A southern plantation owner should not get to determine whether they want to celebrate and rebrand the Confederate flag. Only the LGBTQ+ community could tell the world that the word “queer” is no longer an insult but a designation which it takes with pride. Only a community that has been brutalized by a symbol can truly reclaim it; it is their prerogative. We must be cognizant of this as some of us try to rebrand symbols which our ancestors and even our peers continue to use to oppress.

Black Americans, as a collective, have deemed the confederate battle flag as a symbol of hate. The flag represents a traitorous nation, a racist nation. It represents a shameful time in our history, where our citizens chose secession over abolition. Yet countless white bearers of this flag have tried justifying its continued display. Sometimes their argument includes states’ rights, sometimes it includes heritage.

But this convoluted reasoning falls short of undercutting their rampant racist philosophies. What states’ rights are these insurrectionists referring to? What states’ rights was their beloved Confederacy’s constitution referring to? The Confederate States of America (CSA) made virtually no changes to its constitution regarding the general issue of state sovereignty. In fact, the right to register voters was ceded by the participating states to the federal government. But the main differences were on slave ownership. Four entire clauses were dedicated to the continuity of slavery in the CSA.

These clauses are what this flag primarily stands for, and there have been no efforts to reclaim this flag to possess a different meaning despite the lackluster justifications of 21st-century conservatives. The descendants of slaves in our country have deemed this flag as a symbol of racism, not states’ rights. In fact, the conflation of the Confederate flag with the Gadsden “Don’t Tread on Me” flag has led to a diminishing of the meanings behind the latter. A true flag of states’ rights now stands as an additional banner of racism and bigotry. As African-Americans have shunned flags bearing racist histories, these symbols should be left in museums as markers of our dark past.

Just as the Gadsden flag has lost its initial meaning, so has the swastika. This symbol was prominent in many cultures and religions before its adoption by the Third Reich. Most notable was its prevalence in Hinduism. This symbol of peace and success slowly turned into one of Aryan supremacy, of the Holocaust. The Jewish community, as a whole, decided against reclaiming the swastika with its initial meaning. Since they were the oppressed, the ones who this symbol targeted, their demarcation of this symbol as one of hate is the one that stands and rightfully so. The persecuted can reclaim, the tyrant cannot.

This symbolism pervades our daily lexicon as well. In the realm of racism, the most infamous example of this remains the N-word: a word whose use was initiated by cruel slave-owners. Many African-Americans have started to embrace this slur as part of their colloquial vernacular, but it has also been made abundantly clear that other demographics are not welcome in throwing this word around.

Even today, when this derogatory term is used by other races, it is sometimes preceded by terms like “sand” to widen the scope of racism and is always accompanied by a bigoted tone. This is the status of the N-word, and those of us outside of the community must not overstep these boundaries. The N-word has yet to achieve a neutral or positive connotation. Chicano, an insult turned identifier, is often used to describe Mexican-American culture. The N-word’s path has simply not been the same as that of the word Chicano, and it is reckless of us to assume that it is.

Prejudiced language, however, is not exclusive to racism. It permeates our vocabulary to direct stigma at every group which has been looked down upon at some point in our societal history, including but not limited to homophobia. Many slurs have been directed at this community, some reclaimed, some not so. The Fa-word is a six-letter term, meant to anger, meant to disgust. While some in the LGBTQ+ community have tried reclaiming this word in a similar fashion to Black Americans and the N-word, efforts still have a ways to go.

There has, however, been large success, in rebranding another expression, “queer.” This term has been reappropriated by the queer community to a point where it is rarely seen as an insult. Instead, many people use the phrase in passing as a categorical term to simply refer to this community. The queer community has reclaimed this insult and has made it into a badge of honor. They have chosen to associate a positive connotation with this word, and it is the rest of our responsibility to take this community’s lead. The scorner or descendent of a naysayer must stand back as subjugated groups decide which symbols to disavow and which to reclaim.

What beats us down is not our differences, nor is it necessarily our divisiveness. Instead, it is when we treat each other’s hurt as nothing but merely a game, a trivial sport. This trauma is not simply a split end, an annoyance that can be cut, tossed, and forgotten. The relics of tyranny, swastikas, and slurs still seep through our nation of stripes and stars. We glow varied colors, come from different mothers, and are taught to respect each other, embracing tics and stutters. Yet we slip into factions when we ignore facts, history, and emotions on which we should all agree and act on. For America, we must debate with meraki, while being sensitive to the other side.

The debate over offensive symbolism is not a two-sided one, and it is time to stop acting like it is. Those who have faced unnecessary humiliation and ridicule, either personally or generationally, are the only ones that can make these decisions.

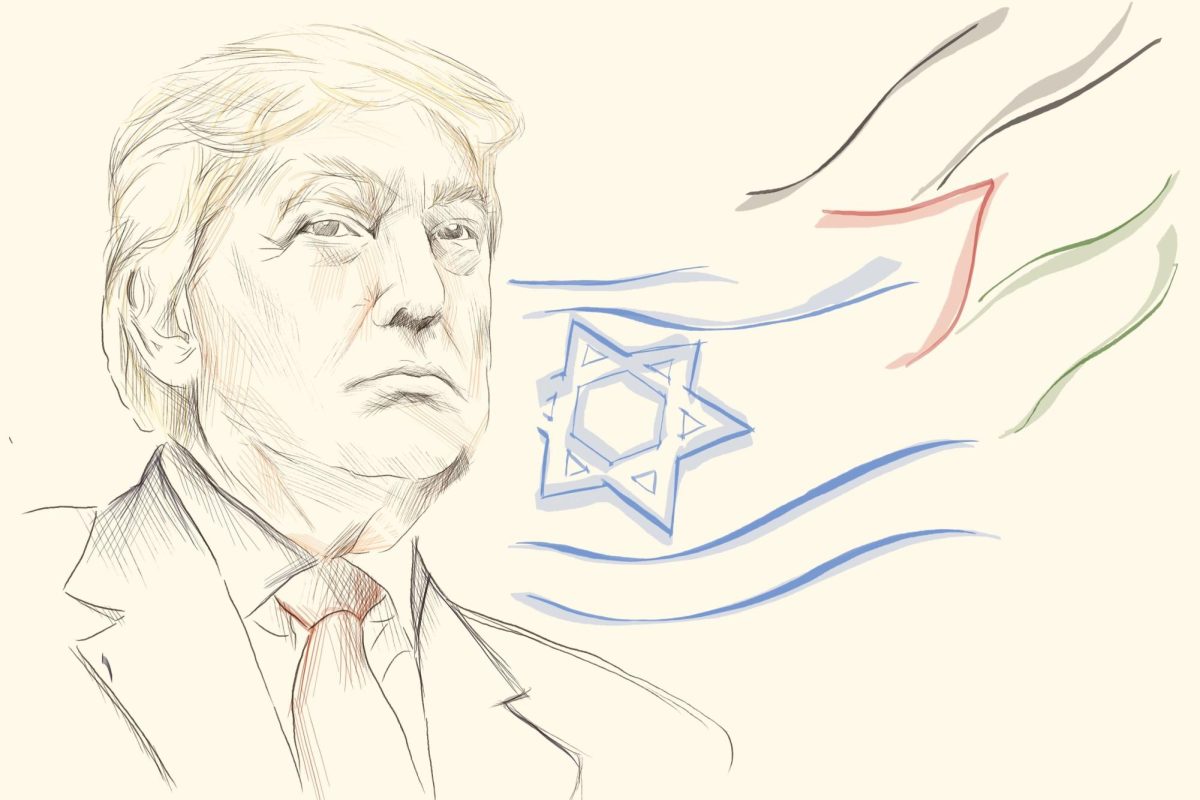

Art by Angela Liang for the UC San Diego Guardian

Doug Saint Carter • Jan 26, 2021 at 3:29 pm

So the image of a black clinched fist can’t be considered offensive by whites? What about the hate filled BLM movement? All I’ve seen is sheer hatred coming from those folks. I’m offended. The need for improvement is much greater 4 blacks than whites.