Without a doubt, any undergraduate student here at UC San Diego has been or will be, subjected to examination after examination where their success is determined by the number of check marks on a pristinely printed and neatly collated stack of rubrics. For better or for worse, the administration has birthed an obscenely diverse population of rubric-based grading styles in efforts to standardize the educational process to all individuals.

Virtually all professors implement some form of concrete standards by which student performance may be assessed, such as an answer key for a multiple choice exam, a checklist for a lab report, or a list of criteria for a successful essay. However, one professor might follow the rubric with the mercilessness of a drill sergeant and another might grade with the stringency of a campus police officer “supervising” the annual Sun God Music Festival. And, though some might consider the strictness or laxness of a professor’s assessment style merely an acquired taste, the effect on students of a professor’s particular rubric-based assessment style is far more substantial than a potential letter grade.

The problem is not with rubrics themselves. Rather, the problem arises from the occasional obsession with rubrics. Afterall, rubrics do allow professors to grade the works of their students with minimal bias and remarkable consistency. Moreover, rubrics demand a standard of quality from students’ assignments that reflect the expectations that will almost certainly be placed on graduates by future employers and higher-ups. That being said, the wide overuse of rubrics as a means of assigning grades stamps out any desire to learn and replaces it with a need to fit into a neat box of preordained criteria.

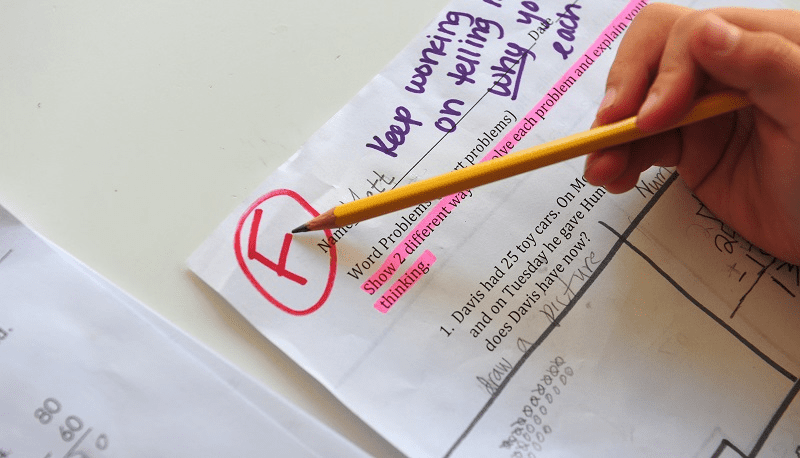

To that point, a professor’s insistence that a student strictly abides by a rubric is nothing short of Pavlovian conditioning. In such a classroom experiment, if the test subject submits to the rubric, it will be rewarded with an acceptable grade. If the test subject strays from the rubric, though, it will be punished with poor marks. The results of this experiment could be hypothesized by any individual with half of a brain: students subjected to strictly enforced rubrics either learn to satisfy the grading criteria or to drop the course within four weeks.

This kind of conditioning does nothing to foster the next innovators of the future as it suggests to students that their opinions are insubordinate to those of their professors. Furthermore, professors insistent on ignorantly upholding their rubric in the face of any and all dissenting voices are effectively coaxing their students from the pastures of creativity to the butchery of conformity, where they file down on the conveyor belt of uniformity.

A study conducted by KH Kim, Ph.D. involving 270,000 youths and adults, revealed that American creativity, after a steady increase between 1966 and 1990, has experienced a substantial decline. According to Kim, this failure was a result of the divorce of educational institutions from a philosophy that emphasizes the importance of teaching students non-conformity, risk-taking, and curiosity. The rubric-based grading system is one facet to blame for the decline in American creativity as it inherently contradicts those three words.

Creativity fuels discovery and innovation, so the urgency of these qualities should supersede the rigid standards that comes with the rubric ubiquity. UCSD is a tier-one research university with a reputation built on the groundbreaking discoveries and innovations of its affiliates. Thus, if UCSD wants to make a tradition of this reputation, it must invest in the future by encouraging risk-taking rather than caution at the undergraduate level and nurturing students who are daring enough to think outside the rubric.