Kawasaki Disease is a vascular disease seen in children that involves inflammation of the blood vessels. The disease was first described in 1967 by Dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki at the Tokyo Red Cross Medical Center and Honolulu, Hawaii in 1976 by another medical team. The causes of the syndrome are still unknown, but researchers are beginning to think it may be a viral or bacterial agent, as the disease seems to occur in outbreaks. No theory of its cause has been proven, but scientists do believe that it is not contagious and that certain genes may make a child more susceptible than others. Kawasaki disease is one of the leading causes of acquired heart disease in children, but few sustain lasting heart damage with treatment.

Possible complications of the disease include inflammation of blood vessels that usually supply blood to the heart, inflammation of the heart muscle, and heart valve issues. Weakening of the coronary arteries can lead to an aneurysm, an enlargement or swelling of the blood vessel wall. For a very small amount of children who sustain artery damage, Kawasaki disease can be fatal even with treatment. The disease also has some associated risk factors — kids under the age of five years are most at risk of the disease, boys are more likely to acquire it than girls, and children of Asian or Pacific Islander descent have higher rates of contracting the disease. While young children are usually diagnosed, the disease can also occur in older children and adults.

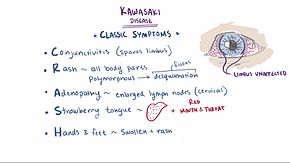

Kawasaki typically presents in three phases of symptoms. The first phase’s symptoms may include a high fever (above 102.2 degrees Fahrenheit) lasting for over three days, very red eyes without thick discharge, a rash on the main body and genital area, swollen lymph nodes on the neck, a red swollen tongue (also known as a “strawberry tongue”), cracked and dry lips, and swollen red skin on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. The second phase of symptoms could include peeling of the skin on the hands and feet often in large sheets, diarrhea, joint pain, abdominal pain, and vomiting. In the third phase of the disease, symptoms will eventually fade away unless complications develop, and it could take as long as eight weeks for energy levels of the patient to return to normal. Treating the disease within 10 days of symptoms presenting can greatly reduce the chance of lasting damage on the body.

There are no specific lab tests to diagnose Kawasaki disease, but patients initially show higher levels acute-phase reactants erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and alpha1-antitrypsin. In the absence of a specific lab test, the American Heart Association has created criteria for diagnosis of a fever lasting more than five days and four of the main symptoms of the disease. If the patient shows more than four of the main symptoms, guidelines say the diagnosis could happen on day four of the fever. Echocardiography is used to monitor possible development of coronary artery aneurysms, with serial echocardiograms taken at the time of diagnosis, two weeks after diagnosis, and six to eight weeks after diagnosis. If there is evidence of a possible aneurysm, echocardiograms may be performed up to a couple years after diagnosis.

The main goal of treatment is to prevent sustained heart damage and coronary artery disease, as well as to relieve the symptoms. Complete doses of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and low doses of aspirin are some of the main treatments that the diagnosed receive. Corticosteroids are usually given to those unresponsive to usual treatment and cyclophosphamide is given to those who are resistant to IVIG. There is a new treatment in Japan to give IVIG-resistant patients ulinastatin, a neutrophil elastase inhibitor typically used to treat patients with pancreatitis. There is currently no known method of prevention of Kawasaki disease.