This past week, the Associated Students at San Diego State University voted to stay the Aztecs, a close decision of 14-12 shedding light on the polarizing issue that has plagued SDSU for decades. “Aztecs,” a name decided on by a committee in 1924, represents a part of SDSU’s history, sports legacy and school pride. However, concerns regarding the extent of appropriation, ignorance and indifference to American Indian history remain equally constant, indicating a divide between those who believe that a name change is too “politically correct” or financially impossible and those who see change as necessary and imminent. Ultimately, by keeping the name “Aztecs,” SDSU is prioritizing tradition and brand security over Native American cultural competence. The school ought to use its role as a powerful academic institution to educate and vocalize concerns regarding appropriation.

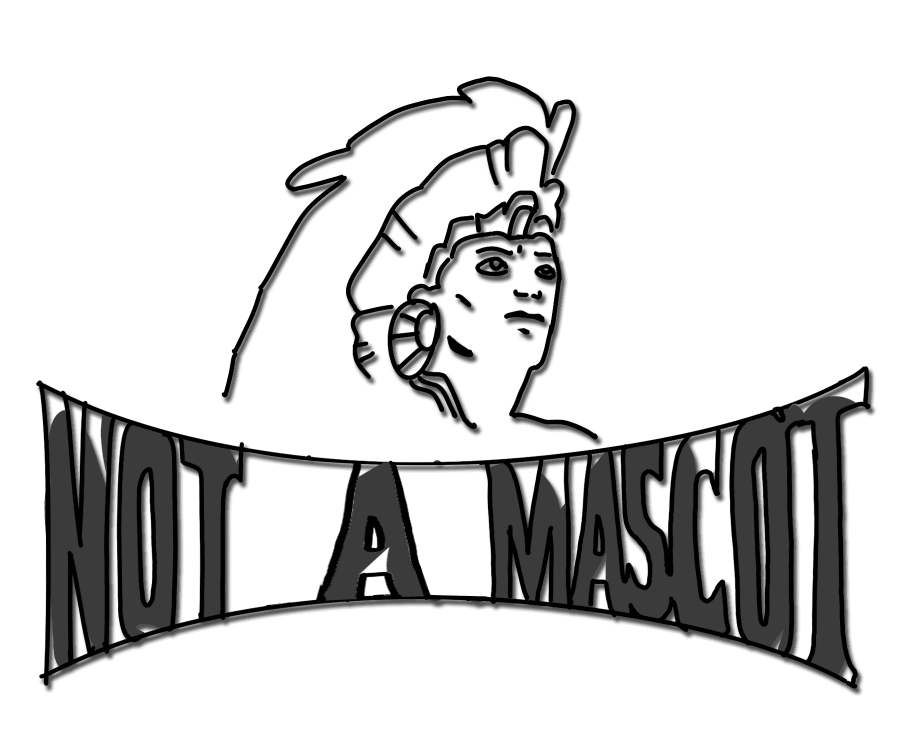

According to SDSU lecturer Ozzie Monge of the American Indian Studies department, the Aztec mascot is a relic from a time when “white supremacy was treated as fact.” In fact, the first time a student dressed up as Monty Montezuma, SDSU’s mascot from 1941 to 2000, was during homecoming, when a student ran onto the field from a teepee, chasing women clad in buckskin. In 2000, the official mascot became the “Aztec warrior,” retiring Monty Montezuma from its revered pedestal in a decision which redirects and writes off the actual issue of appropriation. Despite an NCAA Native American mascot ban, multiple student petitions over many years, and several campus referendums, the name “Aztec” has held strong. Many who proudly adorn themselves in “redface” are quick to point out that their representation of Aztec culture is one rooted in “valor” and “strength.” Similar statements have been made by SDSU President Elliot Hirshman, who wrote that the university’s affiliation with the Aztecs is one reflecting the virtues of the culture. Those in favor of keeping the name lack two fundamental pieces of cultural sharing: historical accuracy and understanding.

For one, the name is geographically incorrect. The Aztecs were located in central Mexico, never the Southwest. To perpetuate this idea that Aztecs were a part of the Wild West history is absurd both as a matter of cultural ignorance and academic grounds. Furthermore, as we consider the mascot’s reduction of Indigenous people to mere objects suitable for pride during sporting events, as well as the student body’s adorning of war bonnets and capturing of the Aztec warrior as something primitive and underdeveloped, it becomes evident that such traditions promote the “noble savage” stereotype. Depicting American Indians as an icon of the American past results in what is commonly referred to “historical amnesia” in reference to the nostalgic idealization of colonialism. While there are no remaining descendants of the Aztecs, trivializing the culture through perpetuating ignorance misrepresents and dehumanizes Indian Americans today, cementing their label as an “other” and ignoring their modern day predicaments.

Many opponents of this change in mascot have argued that its economic effect will be downward, even disastrous for SDSU. However, previous examples of universities shifting their mascots away from Native American imagery — a large number, given the NCAA’s 2005 ban — have proven to yield a range of financial effects, many of them being beneficial in the long run. According to a study conducted by Emory University, the prediction for a university who changes their mascot away from something initially referencing Native American culture entails a one-to-two-year period of immediate negative effects, followed by positive returns whose roots are multi-faceted.

Take Carthage College in Wisconsin, one of the colleges to rebrand after the NCAA prohibited usage of “Indian nicknames, mascots, logos and other imagery at postseason events,” according to ESPN. As pointed out in a marketing analysis by Patrick Hruby, the short-term negative effects and $100,000 cost of breaking tradition ultimately had no lasting effect on alumni support and donations. While a change in mascot may deter some alumni, it would certainly engage those who have previously refrained from supporting the university’s teams due to a mascot described by many as insensitive.

Claims that this move is financially irresponsible serve to oversimplify the well-documented fluctuating effects of re-branding within college sports. Conclusively, integral to the decision of whether or not to rebrand is the necessity of having something new to replace the old. As emphasized in a report following changes of university mascots from Native American monikers to otherwise following the NCAA restrictions, those who failed to replace their retired brands with new ones suffered the most. In short, SDSU’s decision alone won’t signal a prosperous or dismal future for its athletics’ brand, and such a complex endeavor shouldn’t be treated as having foreseeable results.

Oversimplification of financial effect aside, the dialogue surrounding rebranding illustrates that many would rather write criticism of the mascot off as oversensitivity. As alumnus and chair of SDSU’s Fowler College of Business remarked, “Today, too often politically correctness goes overboard.” In a similar vein, SDSU’s Executive Associate Athletics Director’s description of the Aztec “logo” as sacred in the weight and conditioning room reduces the “[strength] of the Aztec people” to commercial usage rather than a conveyance of Aztec culture. Such reactions to the calls for name change are examples, as co-author of the proposed resolution Marissa Mendoza stated, of “a majority [telling] a minority how they feel and [putting a price on their oppression].” In a broader sense, the stark opposition to a change in brand — and the refusal to see criticism of an existing brand as more than “political correctness” — signals that adherence to recent tradition outweighs openness to ongoing dialogue. The decision to keep the Aztec name indicates both a lack of empathy regarding cultural tokening and misrepresentation, and a lack of dialogue regarding the financial concerns. Ultimately, SDSU can and should respect its history as an institution without perpetuating its tired and offensive traditions.

Quinn Pieper // Opinion Editor

Aarthi Venkat // Associate Editor

Jeff Naiman • Apr 26, 2017 at 11:26 am

So according to your logic, USC should change its nickname from Trojans to something else. Last I checked that was geographically incorrect. There were no Trojans in LA. I’m offended by the Triton as your school name. As an atheist, I believe it is wrong to have a God as a symbol for a public institution. Also, last I checked, La Jolla is on land, not the deep ocean. So again, geographically incorrect.