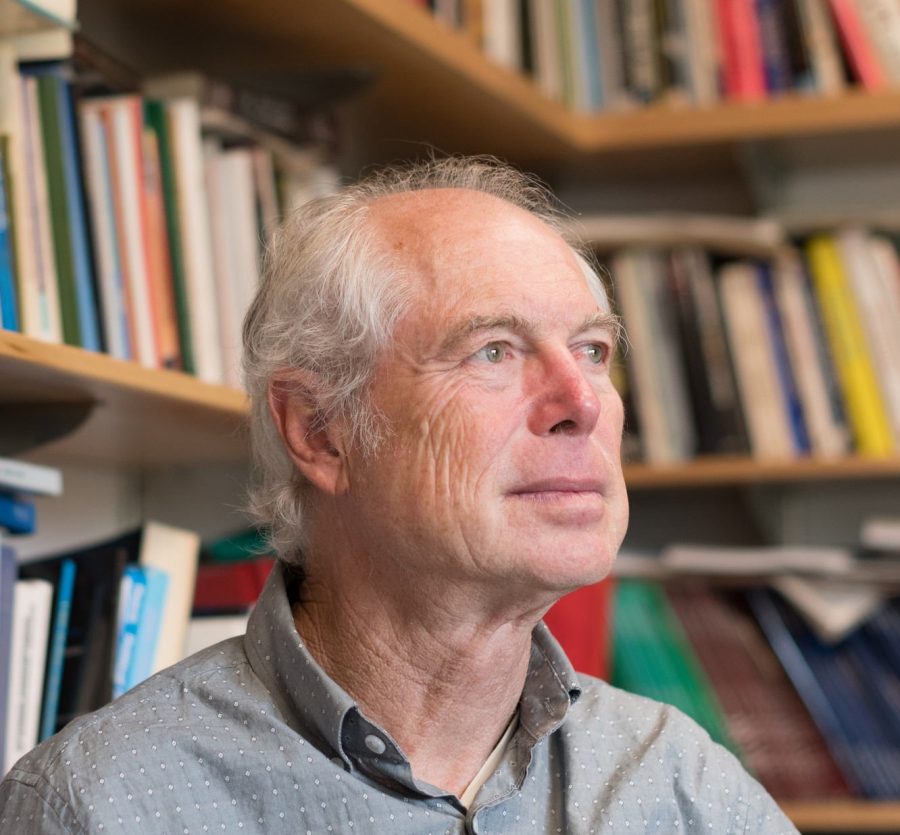

When then-political science graduate student Daniel Hallin set out to write his final dissertation on public opinion and the Vietnam War, he stumbled upon the budding field that excited and thrilled him. Hallin’s time spent sifting through archived newspapers led him away from political science and into the realm of communication, where he is now a major scholar of journalism and media studies whose work is recognized around the world.

Hallin, UC San Diego’s longest standing communication professor, began his career in scholarship as an undergraduate and then graduate student of UC Berkeley’s political science department.

“I was a high school student in the time of the Vietnam War and post-civil rights movements,” Hallin told the UCSD Guardian, “so I was really interested in politics.”

Although he grew up in the Bay Area and attended UC Berkeley, Hallin shrugs off the idea that such highly politicized environments influenced him to go into political scholarship.

“I wasn’t very practical. I didn’t think about, ‘OK, this is a profession and this is how I will move toward that profession.’ I just wanted to keep studying the things I was studying,” he said.

In graduate school, Hallin was particularly fascinated by political consciousness — the study of how people form their opinions on politics and the outside factors that affect those perceptions. He engaged in public opinion research, mainly surveys, in order to determine how people perceived their relationship to politics.

Hallin chose to write his final dissertation on public opinion of the Vietnam War because, even though it had been a major event during his childhood, he was too young to fully understand its implications for American society. Here, however, Hallin hit a wall. As it was a past event, he couldn’t conduct surveys gauging public opinion of the war, and surveys taken in the 1960s were scarce. Hallin’s solution to his research debacle was to, instead, turn to newspaper articles written during the war, analyzing them as both an archive of the time period as well as a look into the mindset of newspapers’ readers and writers.

“I finally decided I should study media because that’s how people got information about [the war],” Hallin recounts. “That was really unusual in political science at the time. Nobody studied media in those days in political science.”

Hallin’s research, which blended political analysis with communications, marked the beginning of the graduate student’s shift toward communication studies. His final dissertation, which explored the connection between media and the Vietnam War, was extremely unique for his field — perhaps too unique for political science academia.

“Looking back on it, it wouldn’t have been the most practical choice since nobody studied media in political science,” Hallin says, chuckling. “I was just really lucky that there was this strange job opening here at UCSD that was a joint appointment between the communication program — in those days it was not a department, only a program — and the political science department.”

Ultimately, what Hallin considers a series of impractical decisions — entering into scholarship and then studying an extremely niche, practically nonexistent field — in fact made him stand out as a leader of critical communication studies, and his work appealed directly to UCSD’s burgeoning communication program.

From the moment he was introduced to the program in 1980, Hallin dove into the field of communication more intensively than ever before. His alma mater did not offer a communication program at the time, so the young professor was excited to embark upon a new frontier in academia, forging a path for himself as he went. Soon, others followed.

“I started studying something peculiar, but then lots of other people discovered the importance of that and so a whole field of political communication developed [and] then I fit right into that,” he said.

Together Hallin and other joint professors of the communication program who have since retired had the opportunity to build the curriculum from the ground up. What set them apart from other communication departments of the time was their intense focus on critical analysis as opposed to production and communications job training.

“In those days, a lot of communication departments developed as kind of a vocational training rather than as academic departments,” Hallin said. “They were connected to a journalism school or radio, television, film. They taught public relations and things like that. Because we came out of a time of social movements, we didn’t want to train people to become cogs in the industry.”

Instead of practice, Hallin and the other department founders honed their identity around critical analysis and communication theory. Led by trailblazers such as Hallin, the department’s critical theory-based approach to the field has been noticed around the country.

“I had Hallin as a teacher and recognized his name from one of his articles that was actually assigned to me while I was studying abroad in London,” recalls Muir College senior and communication major Allie Glick. “Not only was the article helpful for my class abroad, it was also very cool to have personally had this author as a professor.”

One of Hallin’s most popular works is a book published in 2004 and co-authored with Italian scholar Paolo Mancini titled “Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics.” The book reflects Hallin’s unique position as a communication professor with formal training in political science. He applies strategies of analysis used in comparative politics to the field of media studies, unpacking various systems of European media in a way that is so successful that the book has been translated into 10 different languages.

When Hallin isn’t publishing ground-breaking articles or teaching (COMM 109 in the fall and COMM 104G in the spring), he is reading.

“I read The New York Times every day, which I think is still the best journalism in the U.S. I also listen to NPR a lot,” Hallin said. “Aside from those two, I sample around a lot, partly because this is what I do. It varies a lot from day to day depending on how busy I am, but often it’s like an hour or two depending on what’s going on.”

Despite Hallin’s specialization in journalism and media studies, his favorite class to teach harkens back to the basics.

“I like COMM 10 a lot. I got to teach about a lot of things that weren’t my speciality, and it was interesting in that way,” Hallin explained. He likes the challenge of learning new things. One peek at his bibliography takes him from a doctorate in political science to a book about media systems and finally to an upcoming work with a medical anthropologist about the coverage of healthcare in the media. The diversity of research Hallin brings to UCSD is a driving force behind the communication department’s mission to transform the way we think about communication and communications technologies.

Have questions? Have a story for us to cover? Want to write? Email us at [email protected]