Let me paint you a picture — precisely at 3:27 p.m., my eyelids grow heavy, the lecture slowly melts into a background hum, the attachable desk morphs into a pillow, and, oh no, looks like I’ve fallen asleep again in Chicano Literature, only to be called out by the professor for napping (true story).

Sound familiar? To you, or maybe the unfortunate soul who fell asleep next to you, and is unintentionally using your shoulder for neck support? All too often, I’ve seen students victimized by the midday snooze (and for your voyeurship pleasure, check out “Sleeping Students of UCSD” on Instagram, but don’t laugh too hard, that could be you too …) or have personally succumbed to the afternoon daze once the coffee I brewed earlier that morning wore off.

The answer seems too obvious — simply sleep more at night. But as participants in an institution that schedules class as early as 8 a.m. and as late as 9 p.m., while operating on a scale of “don’t study” to “pull an all nighter,” it’s much more complex. Not to mention, we live in a city with coffee shops that stay open even as the sun goes to bed. It has become too easy to fall into a trap of caffeinated convenience and 12+ hour schedules that perpetuate a need for busyness without the efficacy of productivity.

Holistically, sleep isn’t the only answer either. Because of how our days are constructed, how and what we eat also plays a significant role in our ability to tackle those tasks. Research indicates that in this unique university lifestyle, not only do students seriously lack sleep, but they are also confined to poor dietary options, with health behavior studies indicating that a majority of students rarely have more than one serving of fruits and vegetables a day, if that. And yes, to some capacity, it was my choice to have just coffee for breakfast, but it was a lot faster to down a cup of coffee than make some eggs and toast before catching the bus coming at 7:45 to make it to my 8 a.m.

In a public health study of university students, researchers found that determinants like independence, social structures and the “built environment,” resulting from a blending of the physical and social environment, are often more influential to student nutrition in shaping individual choices. Essentially, while we would like to eat more leafy greens, Pine’s salad bar tucked away in the corner doesn’t always make that the most appealing choice when the pesto shrimp pizza is the first thing you see walking in — suggesting that even the placement of foods in a dining hall draws the eye to convenient, and often unhealthier, options.

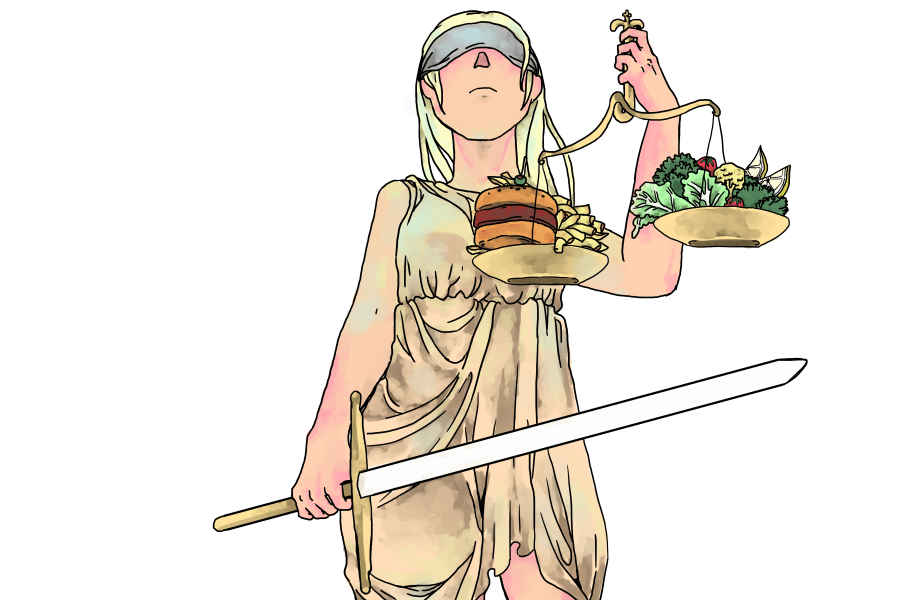

And for students who aren’t assigned meal plans, Price Center doesn’t always cater to a balanced diet. If you’re on a budget, it’s often more economic to spend $5 on a cheeseburger with fries from Burger King than $7.49 on a chicken salad from Santorini’s. Consequently, with sleep being compromised by class and diets that are often filled with empty calories or quick shots of sugar, it’s no wonder we’re losing motivation at the expense of metabolism.

Retrospectively, I understand that we, as students, do have our own responsibility in taking care of ourselves well. But if our options are limited by finances, schedules and accessibility, we can only take ownership of so much. And this doesn’t solely apply to us attending UC San Diego. On a more macro level, for working families that come home from a nine-hour shift to a “food desert” community, it’s hard to shift a locus of control and responsibility to solely the individual.

Truthfully, we, again as students, could be taking more action to improve our sleeping and dietary patterns, but if programs were put into action that gave not only the resources but accessibility to do so, our capacity to make healthy choices would be much more effective. So collectively, let’s look for points of intervention that give us better food for better thought.