Exiting the I-5 South freeway, lined with palm trees, the sun glints off the ocean just a few miles to the right. A cruise through downtown takes you past looming financial buildings and office spaces. Young professionals dressed in baby blue button-ups with sleeves rolled up to their elbows dine outside trendy New American restaurants.

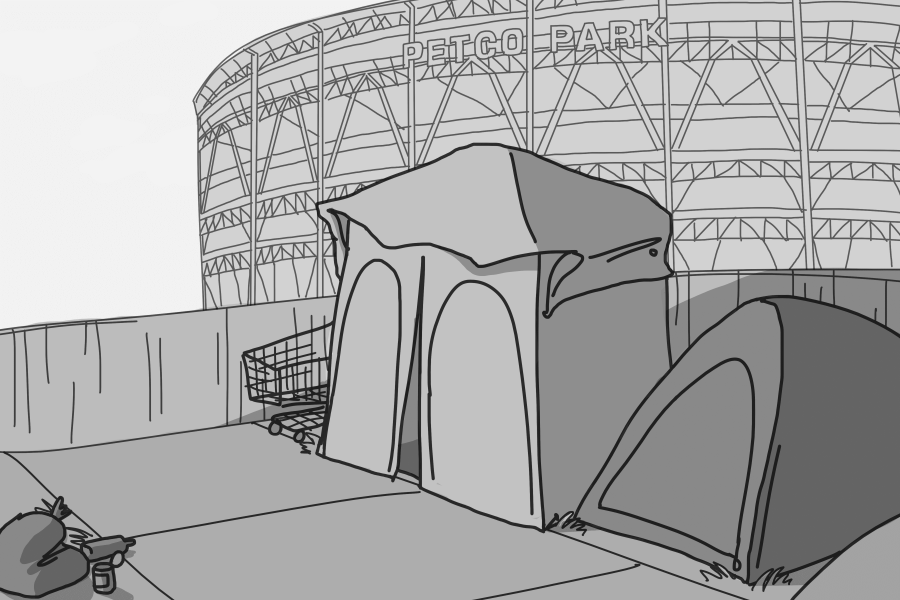

However, just a few blocks from some of the richest real estate in California, there is a semi-permanent homeless settlement. Squeezed between the city’s gorgeous multimillion-dollar, nine-story library and Petco Stadium lies what used to be a plaza. As the homeless population rose and was pushed out of the busier financial sections of the city, people began to take over the plaza. Hundreds of tents line the sidewalks all around the lot. Men and women sleep on benches in the middle of the warm day or squat on the sidewalks. The lot is so heavily populated by homeless that a two-man convoy of policemen on bikes constantly patrols the area. They ride around the block over and over, neutralizing fights and watching out for risks. They are kind to the men and women of the encampments, but their work is endless amidst a sea of tents, trash and people down on their luck.

This homeless square has been a result of anti-loitering laws and other measures which have culminated in a life in which it is not acceptable to be poor and homeless — corralling San Diego’s homeless population slowly into this one block. It has swollen far past its capacity, and cars must swerve around tents that spill out into the roads.

Homelessness is an issue that goes hand in hand with many metropolitan cities across the country. In 2015, officials from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development put New York City at the top of its list, followed by Los Angeles, for the highest population of homeless people. Moving up to fourth place that year, was sunny San Diego. With a countywide homeless population of 8,742 at last count, San Diego’s struggle to reign in its numbers has been a long, slow battle.

According to Richard Gentry, president of the San Diego Housing Commission, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, there are several factors that contribute to the city’s high levels of homelessness. Drug abuse, mental illness and high costs of living are common causes of homelessness and are by no means unique to San Diego; they also contribute to the high homeless populations in Los Angeles and New York City. What is unique about San Diego is its large military community, which has led to the state’s second-highest population of homeless veterans, according to 2015 Department of Veterans Affairs data, in addition to its temperate climate, which makes it possible to sleep outdoors all-year round rather than seek admission into a homeless shelter.

While some have been drawn to San Diego for its mild climate, others have been sent from neighboring states. In February of last year, NBC San Diego reported on a lawsuit against a Las Vegas hospital which bussed more than 500 of its patients to San Diego, San Francisco and several other California cities. Many ended up on the streets.

Granted, San Diego does deserve credit for its efforts. It has come a long way from 2007, when there were a record 10,000 people living without fixed housing. Collaborations between the SDHC, state and local officials, nonprofits and the federal government have helped reduce the homeless population by nearly 2,000, but these efforts have not been enough in comparison to the success of other cities. Within the past ten years, San Diego jumped from 12th to fourth on the list of highest homeless populations because cities formerly at the top of the list have found more efficient ways to combat homelessness, causing their levels to fall faster than San Diego’s.

Why is it that San Diego has been bogged down with the same issues while others have pressed ahead?

One city council staffer is all too familiar with the frustrations San Diego has faced in trying to answer this question.

“It’s a very large and complex problem that no one really has their arms around,” the staffer, who chose not to be identified, told the UCSD Guardian. “Nobody really knows how much is spent [by the city] in trying to help the homeless population in San Diego each year.” The individual believes this is the real issue holding San Diego back: a lack of centralization of organizations and services for the homeless.

They continue, “There’s over 100 different nonprofits within San Diego that are all trying to work on homelessness in San Diego, but there’s not a strong centralized force within San Diego that is leading all of them. Oftentimes, you have wasted resources with a handful of organizations working on the same problem and duplicating each other’s work.”

According to the staffer, this types of inefficient spending is common, especially due to a lack of recordkeeping on different projects. They explain that oftentimes, due to the fragmented nature of the efforts, nonprofits, government programs and city council members all try to tackle the issue with their own “gut feeling” approach. However, they end up competing for resources and pursuing seemingly ineffective programs doomed for failure.

One look at the SDHC’s official website confirms this. It is full of hopeful — but often abandoned — programs aimed at eradicating homelessness in the region like the “Campaign to End Homelessness,” which occurred six years ago and boasts of securing 125 housing vouchers for chronic homeless — without deigning to mention that there are more vouchers to go around than available housing options.

The city’s most recent project, “Housing Our Heroes,” is well behind schedule despite its flashy and inspiring name. The campaign was announced last January by Mayor Kevin Faulconer in his annual “State of the City” address, a speech filled with soaring phrases like “San Diego is leading. San Diego is doing” and “a better San Diego.” According to the speech, the initiative’s goal was to house 1,000 of San Diego’s homeless veteran population by the end of this past year. A glance at the SDHC’s website tells a less optimistic story, with 461 veterans housed at last count.

It’s results like these that speak to the staffer’s concern of resources being spread too thin. San Diego is not apathetic to its homeless problem; however, its current strategy of “going by gut” has resulted in programs and initiatives funded more out of good will than good research.

Jessica Chamberlain, former Homeless Outreach Coordinator for the San Diego branch of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, had more to add about work within the city to end homelessness. Chamberlain explains that, unlike other nonprofits and private services aimed at eradicating homelessness, the Veterans Affair Supportable Housing program she used to be a part of is entirely centered around a scoring process that weighs a veterans’ needs and current risks being homeless. Entitlement to care and a government-issued housing voucher is dependent on a string of numbers computed by VASH case managers using advanced algorithm software provided by the Continuum of Care rather than a subjective assessment conducted by program employees. As ominous as leaving the decision to provide care to a software system may sound, Chamberlain insists it’s been a great strategy for prioritizing need-based veteran housing and hopes other organizations will start adopting it soon. She speaks appraisingly of the Continuum of Care, the federal program whose mission to support local efforts to end homelessness via funding and community tools, such as the computerized case diagnosis system, for its assistance in increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of VASH’s cases. Chamberlain believes getting other organizations to adopt this software, thus pooling city and county homeless services together, will optimize San Diego’s resources.

“It’s really getting the community to shift the way they do things instead of separating the issue into ‘my community’ and ‘our homeless,’” said Chamberlain. “If you’re going to participate in the coordinated entry system we want you to put your resources into our system.”

This coordinated entry system is what Chamberlain envisions as the future of homeless care not just in San Diego, but throughout the county. She explains that if the entire region used the same form of data entry that VASH uses to analyze veterans and match them up with available vouchers, then the county could more easily pool its resources to ensure that everyone’s needs were met. Instead of turning away homeless veterans who don’t score high enough on the federal software program to merit a housing voucher, they could tell them within the same visit which nonprofits they qualify for, and how many beds are available. A centralized care system would directly address Chamberlain and the staffer’s concerns that there are untapped resources floating around the county waiting to be utilized. However, she adds that it isn’t as easy as it sounds.

“Old habits die hard,” Chamberlain says, “It’s a lot of work to try and shift your program into something else. Some nonprofits just don’t have the time and energy to do it. They’re struggling just to perform their existing functions as it is.”

Chamberlain explains that overhauling the VASH system to adopt the Continuum of Care’s suggested scoring software was a long and frustrating process, but it was worth it for long-term investment. The SDHC has been quick to jump on board, but most nonprofits, overwhelmed with work in their filled-to-the-brim shelters, are more concerned with day-to-day operations than with their future. They have yet to set aside the time it would take to adopt the system, and what they don’t excuse as busyness can be chalked up to stubbornness. The result is new programs and projects initiated each year by well-meaning police chiefs, city council members, private citizens and nonprofits, all of which divert resources away from each other.

And if the archaic system of tracking the homeless countywide wasn’t enough of an obstacle, another huge issue is the competitiveness of the rent market. Chamberlain recounts how easy it was to secure housing vouchers from the VA back in 2009, following the recession. Now, as rent prices climb back up to a peak, less landlords are willing to accept VA vouchers, which pay a flat market rate as opposed to the hiked-up prices a landlord could get from the iPhone-toting yuppies filling up downtown San Diego.

As of our phone conversation in December, Chamberlain had on record 126 homeless veterans who had gone through the scoring process with VASH and held physical VASH vouchers in their hands, but who were still living on the streets due to a lack of vacant units. She estimates that the average time it took to move after receiving a voucher in 2009 was about two weeks, whereas now, the majority of veterans are waiting over 90 days to secure housing with the vouchers. When there are more VA vouchers to be handed out than there are open spots, you can finally understand how flawed the system is.

But, there is hope.

The Continuum of Care’s software is ready for use, waiting to be adopted. The VA center and the city are also leading by example through a new federal philosophy introduced in 2014 called “Housing First.” While previous programs have always required that those suffering from substance abuse must becoming sober before being allowed into a homeless shelter, the Housing First movement’s research-backed argument asserts that it is vital to provide people with housing first before being admitted into rehab programs. Many nonprofits, often those with Christian undertones, have had strict rules against substance abusers stepping foot in their shelters, despite the fact that they are typically the ones most likely to be suffering from chronic homelessness, defined as having spent at least a year living without permanent housing. However, the new federally-endorsed ideology of housing before drug rehabilitation has helped to get the chronically homeless off the streets.

In addition, the city deserves recognition for the work they have done to eradicate homelessness in the first place. Chamberlain explained that most states handle homelessness at the county level due to the transiency of the homeless population. Cities are not expected to be responsible for the homeless in their boundaries and typically use that as an excuse to push the issue onto the county. Chamberlain was proud of the San Diego community for taking a stand and asserting that issues of homelessness in their city mattered to them. A huge amount of the work done would not be accomplished if it wasn’t important to San Diego residents. And despite failed projects, it would be wrong to think the city is apathetic to its large homeless population.

Just this past month, Mayor Faulconer hired public relations and communications specialist Stacie Spector to orchestrate a massive overhaul of the homeless care system across San Diego at the various levels of governance. Whereas Chamberlain bemoaned stubborn programs refusing to get on board with the Continuum of Care, Spector’s sole job responsibility will be updating the infrastructure of San Diego, ensuring its ability to serve the homeless and to work with nonprofits, private companies, landlords and officials at the city, county, state and federal levels to create a universal system that has never been seen before. If successful, Spector’s work will be looked at by other cities as a model of homeless care and rehabilitation, a refreshing position to be in after years of criticism.