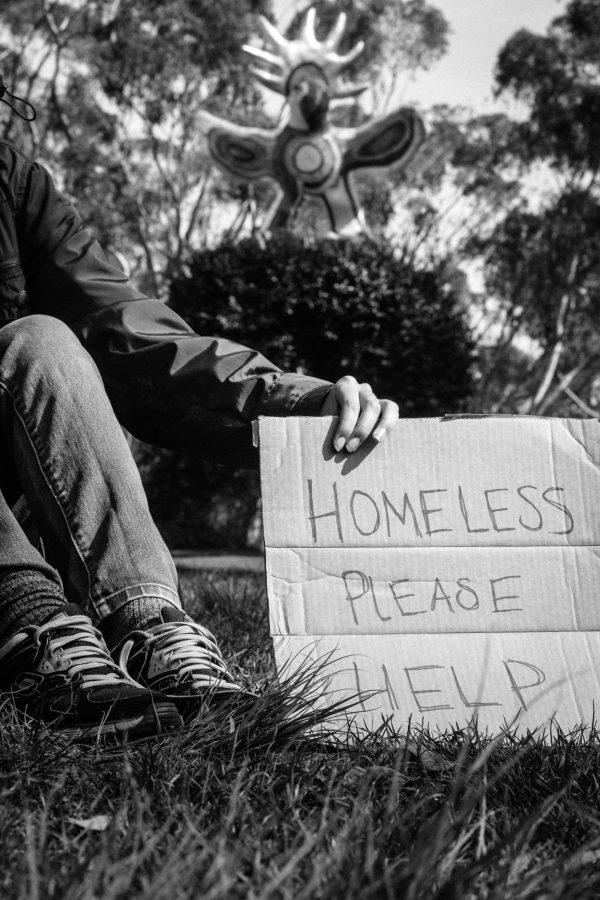

In order to address the 5th highest population of homeless people in the U.S., private and public organizations of San Diego look to data to find more effective ways of helping this hidden population. Among those who need help are UC students — our peers and friends — who suffer from housing and food insecurity.

The number of homeless people living in San Diego is 8,742 right now. In fact, San Diego’s homeless population is currently the fourth highest in the nation, behind only those of Los Angeles, Seattle and New York City, and that number is only expected to increase.

With the problem of homelessness growing, some UCSD students have taken the initiative to help in any way they can. One notable organization on campus is the Homeless Charter, which focuses on feeding the homeless in Downtown San Diego. Executive member Hannah Robinson spoke to the UCSD Guardian about what she and her fellow volunteers do.

“Every Thursday, we organize a sandwich-making event and invite a few organizations to participate, including Greeks, club sports and service orgs. This gives people a fun way to give back to the community,” Robinson told the Guardian. “Every Friday morning, members of our organization hand out sandwiches and water at the homeless shelter, the Alpha Project.”

When it comes to the causes of homelessness, Robinson explains that a multitude of factors, many out of an individual’s control, can lead to a life without a stable home.

“Throughout my years working with this organization, I have interacted with so many different people from so many different backgrounds. It’s hard to say what the leading cause of homelessness is,” Robinson said. “You obviously see your fair share of mental illness and substance abuse, but California has an extremely high cost of living and many people, even with jobs, find themselves unable to afford the expenses of everyday living. Everyone has a different story.”

No matter the cause, both the private and public sectors are changing how they approach the issue. In the past, charitable organizations and government programs focused on providing assistance in the form of substance-abuse counseling, job training and financial responsibility courses prior to placing people in transitional housing or emergency shelters. La Jolla businessowner Michael McConnell volunteers full time on this issue collecting data and coordinating funding efforts for many private as well as public organizations, but overall, he considers himself “an advocate of the homeless.” According to McConnell, only 20 percent of those placed in emergency shelters eventually make it to permanent housing while only 46 percent of those in transitional housing find long-term stable housing.

“The traditional ‘housing readiness’ method assumes the client is not ready for their own permanent housing but, instead, needs temporary shelter and services in order to get ready,” McConnell told the Guardian. “This is a backwards approach that is rejected by communities making data-driven decisions. The client did not need to become ‘homeless ready’ so why would they need to become ‘housing ready?’ Most people need a place of their own to start the process to obtaining better health and self-sufficiency.”

This new method is referred to as Rapid Rehousing and has been embraced by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the San Diego Housing Commission. Using the Housing First method, 72 percent of people we able to make the transition to permanent housing. Although it is effective, this method requires access to housing, which is difficult to obtain in the impacted San Diego area, particularly because of the stigma surrounding homelessness.

“San Diego has a tight rental market, but most of all, landlords need to feel confident that the tenant has the support needed to succeed in their housing,” McConnell said. “The biggest drawback is placing people in permanent housing without the proper support services and connection back to the community. In the rush to build housing first systems we must not let go of the quality of services that are needed to make it work.”

This, of course, requires substantial amounts of funding.

Representative Scott Peters (D-52) has been working the Department of Housing and Urban Development to secure the necessary funding. Looking at 2014, San Diego received only 23rd most funding, despite having the fifth highest homeless population in the United States. In order to combat this, Representative Peters has asked the HUD to open the current formula for the allotment of federal aid up for public comment this coming spring so that San Diego’s homeless can receive a fair amount of assistance.

“Our communities need more resources to get people off of the street, out of shelters and into stable homes so they can hold a job and raise their family,” Peters said in a press release sent to the UCSD Guardian by Peters’ staff. “Secretary Castro has taken significant steps to reduce homelessness across the country, and I support this budget request that will bring more resources to communities like San Diego that are working cooperatively to end homelessness.”

Furthermore, McConnell believes that the best solution for this problem cannot come from public services alone, but through cooperation between public and private organizations.

“The most important partnerships are between the Public Housing Agencies and the County Health and Human Service Agency,” McConnell said. “This is where the marriage of housing and services need to occur. Private funders, like Funders Together to End Homelessness San Diego, need to fund some infrastructure items that public funders cannot. Nonprofit agencies need to provide the best evidence-based services they can. Everyone needs to advocate for elected officials to make this a priority issue.”

In bringing an end to homelessness, it is important to remember that homelessness and housing insecurity affect college students as well. A.S. Council Senator and Thurgood Marshall College sophomore Tara Vahdani explained that housing insecurity is, in many ways, an invisible problem among UCSD students.

“With students on campus, there are ways they act that might not be perceived like the ways we expect homeless people to be,” Vahdani told the Guardian. “The fact that we have a shower to use and a lot of nap spaces in our space [the Women’s Center] means there is more access to resources where you can use these resources without anyone pointing out that you’re housing insecure or that you’re currently homeless.”

In 2014, 20 percent of students skipped meals to save money, according to the Undergraduate Experience Survey. Alarming numbers like these prompted the UCOP to give $75,000 to each UC campus to open food pantries and provide resources to struggling students. Unfortunately, the seed funding given to the Triton Food Pantry, which Vahdani volunteers at, has long since run out.

“It’s kind of been a bit challenging this year because I want to point students to the Food Pantry as a reliable resource but, as someone who volunteers there, and is there every week, I know that that’s not always the case,” Vahdani said.

Vahdani also emphasizes that divorcing food insecurity from housing insecurity in the public consciousness undermines our ability to combat both issues effectively.

“When you look at these two issues, I think they’re both perceived, unfortunately, as flexible expenses and [students] question which one is more timely and which one do [they] need to devote limited resources to,” Vahdani told the Guardian. “I think what is unfortunate is that, with housing insecurity, these questions haven’t really been asked before to students at the UC so there isn’t a known number of how many students across the UC are housing insecure, from my knowledge.”

The Free Application for Federal Student Aid estimates that there are 58,000 homeless students. However, this number only counts students who fit the FAFSA definition of homeless; though FAFSA defines a student as homeless if he or she “lacks fixed, regular and adequate housing,” every student’s status must be determined on a case-by-case basis by the university’s Financial Aid Administrator. In this process students are required to provide documentation from shelters, youth centers, or letters from social workers. Notably, FAFSA’s definition excludes students who live in on-campus residences but do not have places to live during breaks, students who are “couch hopping.”

“If a student is homeless midyear, I don’t know what resource to refer them to,” Vahdani said. “Our university is large enough that we should have emergency housing available for students if they’re suddenly unable to locate a place to live and have advisors who act like a support system that can guide them through the process.”

When it comes to resolving an individual’s problems with housing insecurity, Vahdani recommends contacting one’s college dean as a good first step.

“First, it could help them address your immediate needs, but the second thing that that could do is really bring the issue of housing and food insecurity to the forefront of administrators’ agenda,” Vahdani said. “Then, when my dean of student affairs goes and meets with the deans of the other colleges, or goes and meets with the provost, this is something that they can go and bring up. I don’t think it’s great recommendation but I think it also points to how much more our university has to do to address this need.”

In light of these issues, A.S. President Dominick Suvonnasupa has made it his mission to combat housing insecurity, among several other issues that threaten students’ well-being, during his term in office. For this purpose he is creating the Office of Food and Housing Resources. Suvonnasupa has already written the official language for the constitutional amendment to create the office, and will seek approval from the six college councils this week.

“The design of the office is to make sure that A.S. [Council] is very in-tune and aware of what the different issues surrounding housing and food insecurity are,” Suvonnasupa told the Guardian. “It’s not a simple problem because there are a multitude of layers.”

Suvonnasupa explained that the inspiration for the office came from the experiences of both himself and people he has known.

“There’s definitely a lot of different instances where I talked to students, and even myself — I’ve got some experience in housing insecurity — and it’s always a really challenging thing because it affects every aspect of your educational experience,” Suvonnasupa said. “It affects your ability to study, it affects your ability to work and it affects your ability to live like a student and enjoy your time with your peers.”

The new office will focus heavily on teaching students the skills necessary for living off campus, particularly how to pay rent and budget accordingly. This will make the transition to off-campus housing, which many students are not prepared for, much easier.

Suvonnasupa stressed that housing insecurity comes in many different forms. For instance, interim housing insecurity involves circumstances where a person is left homeless due to an eviction, while systemic housing insecurity happens when a person is simply unable to afford to live in La Jolla.

The Office of Food and Housing is only one part of the A.S. Council president’s plan to tackle this issue, the other being a campus-wide housing insecurity committee that is jointly charged with the Student Affairs Office, the CFO’s office and A.S. Council. Consisting of faculty, administrators and students, the committee will look at the causes of food and housing insecurity and what UCSD institutions are willing to do to deal with them.

The Office will also provide an Off Campus Housing Resource Intern who focuses on tenant issues and legal issues. Furthermore, Student Legal Services already provides a student-accessible lawyer specifically for tenant issues and other legal issues related to off-campus housing.

Suvonnasupa maintains that, in spite of the enormous challenges involved, his administration will work toward eliminating the problem of housing insecurity at UCSD.

“It’s my personal belief that I don’t think any student here should ever have to deal with housing insecurity,” Suvonnasupa said. “While you’re on campus and we have the resources to address these issues, we should.”