AJ Cawood and Nathan Klarer discuss BridgeCrest Medical, a mobile platform for monitoring employee health in high-risk industries.

Over a year ago, Eleanor Roosevelt College fifth-year senior Nathan Klarer came home excited to tell friend and roommate, class of 2011 alumnus AJ Cawood, about an idea he had been incubating. Klarer, a bioengineering major, had a new idea — a health monitoring interface that he intended for industry use — that Cawood believed had great potential in hazardous industries. Last February, they launched their very own company, BridgeCrest Medical. This past March, they made a deal with their first, major international client.

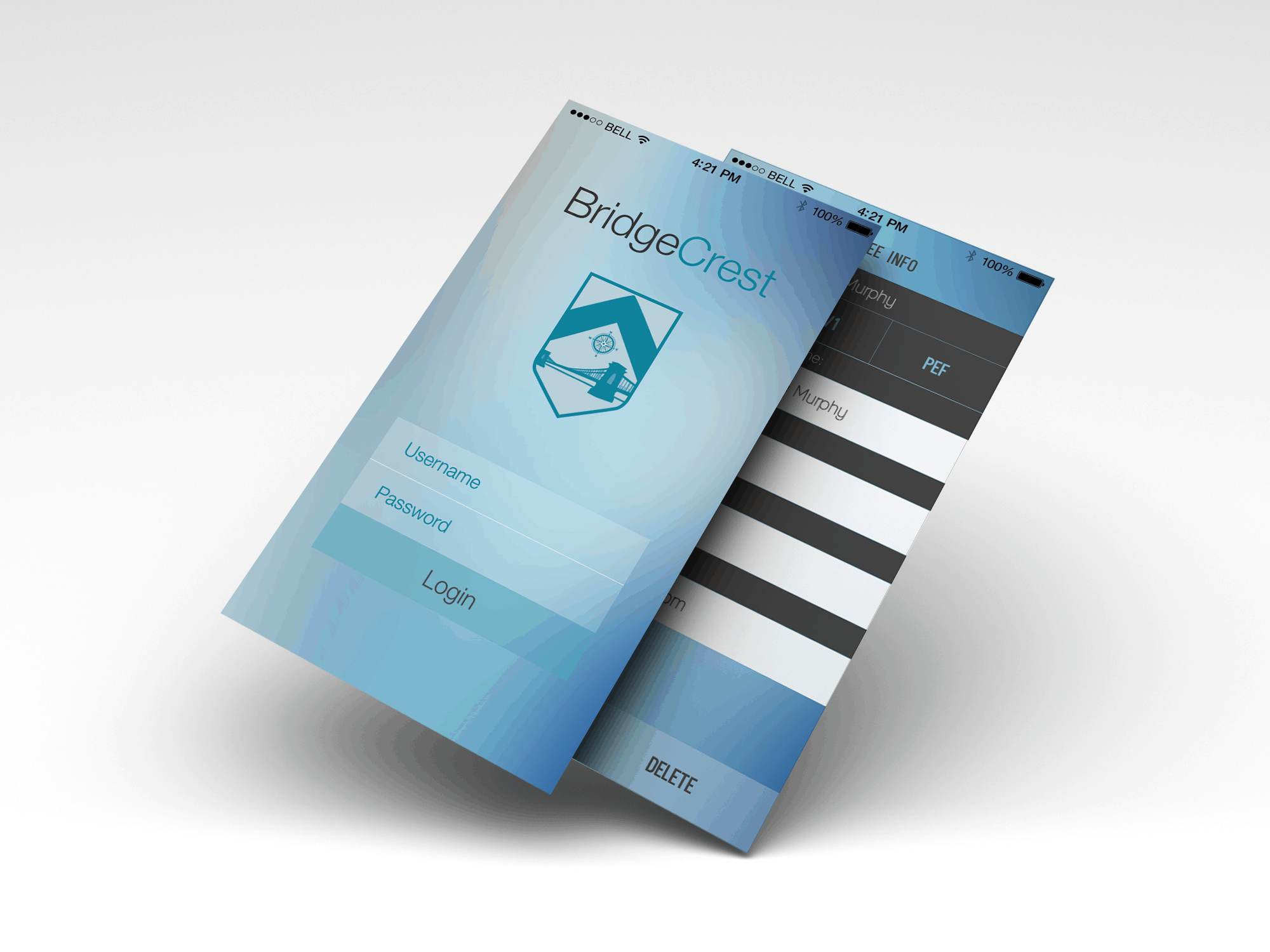

BridgeCrest is a digital platform that runs diagnostics from medical devices connected via Bluetooth and displays the data on a tablet or other mobile device and stores the data for analytics. The platform is Bluetooth compatible with certain monitors used to measure health data, including blood pressure, lung function, hearing loss and drug use.

“BridgeCrest is designed to go out to remote locations where there isn’t any existing health infrastructure,” Cawood said.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires industries to take preventative measures in the workplace. BridgeCrest adds to this preventative mindset.

“[Companies] can catch different health trends before they become problematic and make sure that the workers at the site have the highest quality of health,” Klarer said.

Though the new company remains a small team of 11, mostly software engineers, it has progressed quickly. BridgeCrest has already secured a big client in Africa whose name could not be released. This connection puts them closer to their goal of reaching more countries. Next month, they plan to reach out to other countries in South America and Africa, in addition to North America.

Cawood claims that their solution received a cascade of positive feedback at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada Convention, a large mining convention that was held in Toronto, Canada of March this year. This was where they met their international client.

“There hasn’t really been any major mobile technology [in medical diagnostics],” Cawood said. “[Companies] are pretty excited that the tablets that they’re used to can provide this kind of insight.”

They credit their success to a network of contacts in the medical and business field. BridgeCrest features a board of directors whose purpose is to consult on the latest in medical technology. Dr. Steven Steinhubl, director for Digital Medicine at the Scripps Translational Science Institute, is only one of the many board members.

“We partner with the top mobile device experts in the world,” Klarer said. “The makers of these [diagnostic] devices come to Scripps to have their devices validated because Scripps is really the leading institution in the world for mobile medicine … The devices that Dr. Steinhubl likes he will recommend to us, and then we decide if we want to incorporate that technology into the platform or not.”

Cawood and Klarer have come a long way from the days when they had to juggle both coursework and the founding of their company. When asked about how they handled their obligations between their education and their company, Klarer and Cawood laughed, noting that they squeezed as much work as they could into their spare time.

As for future plans, Cawood and Klarer are set to conduct a study in South America where they will be employing and integrating wearable devices with their platform. They hope to direct their platform toward nonprofit purposes.

“We want to take what we have done [in the mining gap] and direct it into the nonprofit sector,” Cawood said. “This concept not only has value in the corporate sector but also on world governments, nonprofit groups like the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders … We want to make an impact on poor populations.”

After around a year of managing BridgeCrest, Cawood and Klarer are confident and optimistic about their company’s future.

“We think what we have is pretty unique, and we’ll be pushing the boundaries of what’s been done,” Cawood said.