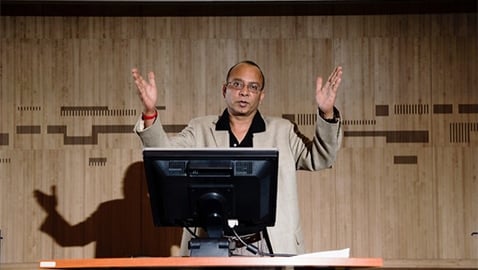

UCSD physics professor Vivek Sharma talks about chasing the Higgs Boson-the fundamental particle of the universe-and verifying his team’s 2012 results to confirm its existence

UCSD physics professor Vivek Sharma is someone who teaches from a textbook, and by the end of the year, he will probably be in one himself. Sharma led an international research team called the Compact Muon Solenoid to find a particle in July 2012 that looks a lot like the Higgs boson, commonly called the “God Particle.” The Higgs boson is hypothesized to be an invisible particle which creates mass and is essentially the Moby Dick of particle physics — physicists have been hunting for it for over 50 years. Now, Sharma is working with CMS to verify their results and prove that the particle they identified is, indeed, the Higgs boson.

I figured that 3,000 years later, […] I could begin to do research which would answer the questions of these ancient sages from thousands of years ago. – Vivek Sharma

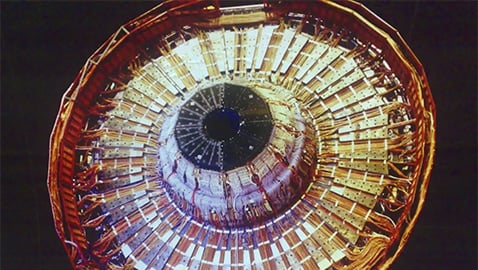

For such a high-stakes project, two teams, CMS and ATLAS, were appointed to conduct experiments with independently designed equipment of equal capabilities so that they could check one another’s end results. Sharma described the year-long race against ATLAS to find the Higgs boson, which started in 2011, as very intense. An average day for him spanned from 9 a.m. to 1 a.m., and he never got more than six hours of sleep per night that year.

“Once you have that tantalizing hint [that the boson exists], the adrenaline flows in an incredible way,” Sharma said. “You don’t need to sleep. You just live on the thrill of the chase.”

After an adrenaline-filled year of research, the two teams presented their findings in front of thousands of scientists at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN, in Geneva, Switzerland. Hundreds of thousands more viewed the presentation online.

“The atmosphere was like a Super Bowl or World Cup,” Sharma said.

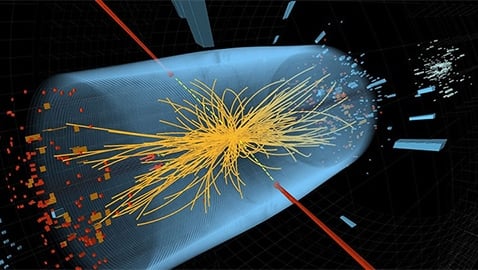

To try and catch a glimpse of the Higgs boson, both teams used the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, which is a 27-kilometer ring built 100 meters underground and cooled in liquid helium to 1.85 Kelvin (-456.34 degrees Fahrenheit), barely above absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature. CMS and ATLAS used this machine to smash particles together at speeds just three meters per second slower than the speed of light. Both teams, who weren’t allowed to share their findings with one another during their year of research in order to prevent bias, collected similar data that strongly suggested the existence of a particle like the Higgs boson. They both demonstrated that there was only a one in 3.5 million chance that their similar results were due to chance.

“At the end of the day, we’re lucky [CMS] didn’t see a pink elephant and [ATLAS] didn’t see a green zebra,” Sharma said. “We both saw the Higgs boson.”

The search has been in progress since 1964, when James Higgs, a theoretical physicist, proposed the existence of this particle in a hypothesis that seemed so bizarre to many scientists that Sharma likens it to the Beatles song “We All Live in a Yellow Submarine.”

Higgs’ theory suggests that there exists an invisible “field” that fills the entire universe and cannot be turned off. Some things interact with the field more than others, and the more something interacts with the field, the greater its mass. For instance, electrons and protons — what humans are composed of — play with the field, so we have mass. On the other hand, light particles, called photons, don’t play with the field at all. As a result, light is massless.

Higgs hypothesized that this invisible field is made of invisible particles called Higgs bosons. These particles are what play with everything in the universe and create mass. In fact, if these bosons didn’t exist, the discipline of particle physics would be compromised, since many of its theories have already assumed the existence of the Higgs boson. More importantly, if the Higgs boson didn’t exist, we wouldn’t either, as the particles that make us up would simply fly off into space as massless particles.

Sharma’s fascination with the Higgs boson is rooted in the Hindu scriptures, particularly the Rigveda, which he read when he was about 18 years old. The Rigveda includes the “Song of Creation,” in which the ancient sages speculate about how the world and the universe came to be.

“At that time, I figured that 3,000 years later, by using technology, I could begin to do research which would answer the questions of these ancient sages from thousands of years ago,” Sharma said. “The idea was to use the most modern technology to answer these questions and the curiosities of our prior generations on how the world came to be. And that’s when I decided to go into particle physics.”

The questions of the ancient sages still remain unanswered, however, as CMS and ATLAS have yet to prove that the particle they identified is, in fact, the Higgs boson.

“Really, what we could say was that it walked like a duck, it talks like a duck, so it must be a duck,” Sharma said.

Both experiments need more data — more Higgs boson candidates — to get more evidence that the Higgs boson exists. Thus far, they have already identified around 250 of them. Another complicating factor is that, for all we know, there may be more than one Higgs boson out there — possibly even five, as Sharma suggests. Researchers still have a long way to go until they can say that they have truly found the so-called “God Particle.”

Aside from research, Sharma is currently teaching PHYS 2A, a mechanics course, at UCSD and plans to teach the same course next winter quarter. But once Spring Quarter 2015 begins, Sharma will be off to CERN again, just as the LHC reopens for the next round of experiments. And although the trip from La Jolla to Geneva comprises of 24 hours of travel, Sharma still plans to fly to CERN every 4 weeks for his research.

In the meantime, Sharma and the rest of the CMS team are working on publishing results from their race to find the Higgs boson.

“These [articles] are for history,” Sharma said. “This is how we will be judged — by our publications.”

Sharma is also around halfway through writing a memoir about his experiences while working on the Higgs boson project. Though he’s writing about the project in past tense, he accepts that the quest for the “God Particle” is very much in the present and is far from over.

“Think of a painting,” Sharma said. “[The discovery in July 2012] was just a sketch. What needed to be done with the data we have accumulated since July 4 was to actually verify and fill in that sketch — complete the portrait, to establish the DNA of this particle. This, we are getting close to doing.”