For as long as sports have been played in front of fans, they’ve been big money. Gaius Appuleius Diocles, the ancient Roman charioteer often — dubiously — referred to as the highest-paid athlete of all time, reportedly earned enough money to supply grain to Rome for a year, or to pay the salaries of every ordinary soldier in the Roman army for a fifth of a year. In more recent years, American teams have become the realm of sports-fan billionaires too rich for mere jets but too poor to launch their own space programs.

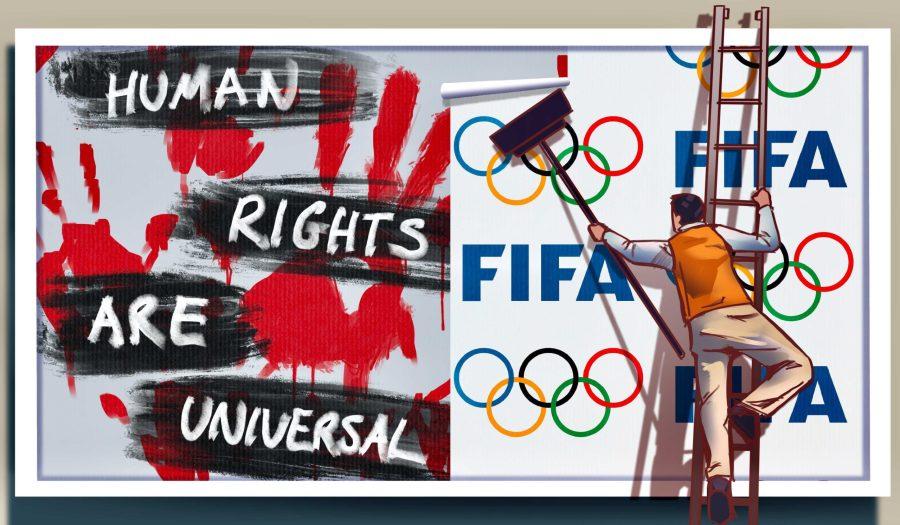

Setting aside the ethics of spending $2.3 billion to own the Carolina Panthers, sports have increasingly been used to launder the reputations of some far more unsavory characters, especially undemocratic regimes around the world. This process is referred to as “sportswashing,” a term first used by opponents of the European Games being hosted in Azerbaijan, whose authoritarian government under Ilham Aliyev has rigged elections, jailed and tortured opponents, and stolen millions from government coffers.

Sportswashing, of course, isn’t a new phenomenon. The 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin were seen by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi propaganda machine as a way to improve their international reputation and espouse their ideals of Aryan supremacy, and famed boxing matches like the “Thrilla in Manila” and the “Rumble in the Jungle” were promoted by dictators to bolster their nations’ image.

But as sports have become more international than ever, and as big public spending on events like the World Cup and Olympics are increasingly unpopular in democracies, sportswashing is seemingly involved in a larger proportion of events than ever. The last World Cup was held in Russia, and the next Olympics will be in China. This week’s Formula One race and next year’s World Cup will both be in Qatar. All of these nations have poor human rights records, including censorship and punishment of any opposition, and all will shell out tens of billions to paper over those actions.

So we all know sportswashing is happening, and everyone apart from the major international bodies that run global athletics seem to acknowledge it. The difficult question that we don’t really have the answer to yet is: now what? Is there anything the average fan can do to strike back against it?

The easiest and most often suggested answer is a boycott of events held by dictatorial regimes, using the power of the dollar to pressure organizations like FIFA and the IOC to think more carefully about their host selections. But that’s easier said than done for sports fans, who often live for and organize their lives around events like the World Cup or Olympics. It’s hard to believe that a fan boycott large enough to affect the bottom line of either event is possible, since at the end of the day, people’s love for what happens on the field is too great to be bothered by what happens off it.

Things get more complicated when the sportswashing isn’t just in the form of a one-off event, but rather involves the takeover of your favorite team. This is a familiar subject for fans of European soccer, where Qatar owns Paris Saint-Germain, the United Arab Emirates own Manchester City, and, as of last month, Saudi Arabia owns Newcastle United.

Being a supporter of a soccer team in Europe is baked deep into a city’s identity — it’s the sort of thing you inherit from your parents and pass on to your children, the sort of passion that holds a community together. The idea that the fans of Newcastle should have to abandon that because a Saudi Arabian sovereign wealth fund bought their team is unthinkable. But even if that’s true, it leaves fans in a deeply unsatisfying position, where every success on the field and every ticket or jersey sale goes to the pockets of a repressive autocracy. That’s not something fun to root for, as hard as fans may try to ignore it.

To some degree, sportswashing is just a consequence of the money-oriented parameters of our society. Deep down, we all know that a sports team is just a corporation, a billion-dollar enterprise that we support for purely regional reasons and wear jerseys for, and yet we still root for them nonetheless. While most fans can pretend their owner doesn’t exist and try to focus on the players themselves, that pretense is difficult to maintain and is actively harmful when that owner is a government that regularly harms human rights.

Put another way, perhaps sportswashing isn’t anything special at all. Maybe it’s just a stark reminder that the sports we love, like the music that we can remember all the words to, the video games that we stay up all night playing, and the movies we cry watching, are corporate products just like any other. That’s a tough pill to swallow, and how we react to it is obviously a difficult choice.

But since sportswashing isn’t going away, there are some things we can do in the world of sports to combat it. One would be to seek increased fan sovereignty over sports teams — think of the German “50+1” rule that means that, in most cases, club supporters own the majority of their favorite teams. But that massive shift in ownership structure is a pie-in-the-sky goal, especially on this side of the pond.

So, when we can, athletes and fans should speak out for human rights, especially in the arenas of the very regimes that seek to repress them. Sportswashing exists because regimes like Qatar want to legitimize their authoritarian states on the global level. If there’s anything we can do to stop that, it’s to make sure that when autocracies host sporting events and buy sports teams, it doesn’t improve their reputations, but rather shines a light on their human rights abuses. If China has to host the Olympics, then let it give us an opportunity to call out their persecution of minorities, repression of civil liberties, and lack of democracy rather than allow its government to spend tens of billions of dollars on a careful public relations campaign to project a more positive image.

We saw two examples of that behavior in the past week. First, the Danish football association released a strongly worded statement that they would use their time in Qatar during the World Cup to advocate for human rights and migrant workers. Second, Lewis Hamilton, by far the foremost Formula One driver of the last decade and the sport’s biggest star, has repeatedly used his platform to criticize Qatar’s treatment of the LGBTQ community.

These are ultimately just statements. Real actions that affect human rights take place among governments, not individuals; especially for international human rights crises the average person might not know about, the awareness star athletes can bring is vital to manufacturing the political will for change.

However,pressure needs to be maintained until concrete action occurs. Governments will often use sports events to project a new, kinder face, but they are much more reluctant to enact real change. Qatar has made a great deal of promises about labor reform due to the scrutiny brought on by the World Cup, but Amnesty International noted this week that enforcement of these laws is shoddy at best, and exploitation continues.

“By sending a clear signal that labour abuses will not be tolerated, penalizing employers who break laws and protecting workers’ rights, Qatar can give us a tournament that we can all celebrate. But this is yet to be achieved,” said Mark Dummett, Amnesty International’s Global Issues Programme Director.

Fundamentally, sportswashing is a bet that fans can be bought off by the allure of glamorous stadiums and big-name sports clubs, and ignore the human rights violations that lie behind that façade. While we might not be able to fully take back control of sports any time soon, it is imperative for athletes and their fans to use their power to redirect the spotlight towards those crimes against humanity, and make the bet a losing one for undemocratic regimes.

Art by Nicholas Regli for the UCSD Guardian

Pat Bell • Dec 29, 2021 at 9:06 am

Of course they can. Fans are a very strong football force and if they come together they can oppose a service like FIFA. Together we are strong