Will electric scooters lead the future, or become another embarrassing fad?

The first time I rode an electric scooter, I was wearing heels. I was interning in Washington, DC, and running desperately late to an event on Capitol Hill, 1.2 miles away from my work. It was only my second week there and I hadn’t realized how far it was — walking or taking the Metro would take too long, and the nearest Ubers were all several minutes away. I was still in my work heels and a blazer, but I had no other choice.

It wasn’t unusual in DC to see people in business suits scootering around town. It was, after all, a very pedestrian friendly city, and what are electric scooter riders if not hybridized pedestrians?

It was easy; after downloading the app and inputting my payment details, all I had to do was locate the nearest scooter on the map, scan a code on the handlebars, kick off, and go. The electric motor made the ride virtually effortless, and I showed up looking flustered, but not sweaty. Their dockless nature meant I was free to start and stop anywhere, so long as I parked it neatly and out of the way.

In traffic-congested urban areas where traveling by foot is often easier than traveling by car, but a two mile walk that takes 35 minutes doesn’t sound attractive either, the electric scooter provides an alluring alternative.

Upon returning to California for Winter Quarter, I realized that the scooter movement had arrived at UC San Diego too. The 25-minute walk from Roger Revelle College to Rady School of Management could be cut in half with wheels, but not everyone found it useful to bring their own bike to school. Dockless bikes, like the orange Spin bikes that populate UCSD, solved that problem but brought with them a new one: without needing to be anchored to designated bike racks, people began parking them in odd places. Dockless scooters come with the same risks, but they’ve enjoyed greater success on campus and in surrounding areas.

“[The scooters] are small enough where you can just move them out of the way, but it’s harder with bikes and people will just leave them anywhere, like that one bike graveyard on La Jolla Village Drive,” Sixth College senior Elisha Beebe said, referring to a well-known intersection at the edge of campus where bikes are often unceremoniously dumped on the sidewalk.

“I feel like people are pretty responsible with [the scooters] on campus, in other places I’ve seen people hoard them,” Eleanor Roosevelt College sophomore Keely Paris said.

A responsible user base is crucial to the future of these dockless transportation systems. Rules are only as good as the people who follow them.

For example, Bird Scooters require their users to be at least 18 years of age and submit a photo of a valid driver’s license in order to be able to ride. But not every scooter company has these stipulations, and it’s easy for underage users to sidestep these checks by using their parents’ licenses and birthdays. Aside from these lax guidelines, there’s no definitive age demographic of scooter users.

“I do see people using it in Santa Monica who look older, at least. But it’s mostly a young person thing because I heard about them from my cousin who is 15,” Thurgood Marshall College junior Anahita Afshari said.

“I love riding, it’s a very novel and fun experience, especially if it’s a nice day out. If my friends and I see them and we aren’t doing anything or we’re just waiting around, it’s like a toy and we’ll just scoot scoot around.”

But in terms of efficacy, scooters aren’t necessarily her first choice. “If I’m on campus, scootering is way easier because I can go where a car can’t. But if I’m going to CVS or somewhere relatively close, it would be a 20-minute scooter ride [from the Village at Torrey Pines] and it would be less expensive and less hassle to take an Uber,” she said.

When I asked if she would use them to get to work in the future, Afshari said, “It depends on my job but if I were in a city and there were a lot, then yeah, I would. But I don’t think I’d use them past the age of 30, because I feel like it’s a very young person thing to do.”

UCSD is currently home to several scooter-share companies: Bird, Lime, Lyft, and Spin. It’s not uncommon to see electric scooter riders in the fray of bikers, skaters, and pedestrians weaving their way down Library Walk.

I’m not the only college student who uses them to make up for lost time: “I will say I’ve made it to a couple [meetings] because of the scooters that I would have otherwise been late for,” Afshari said.

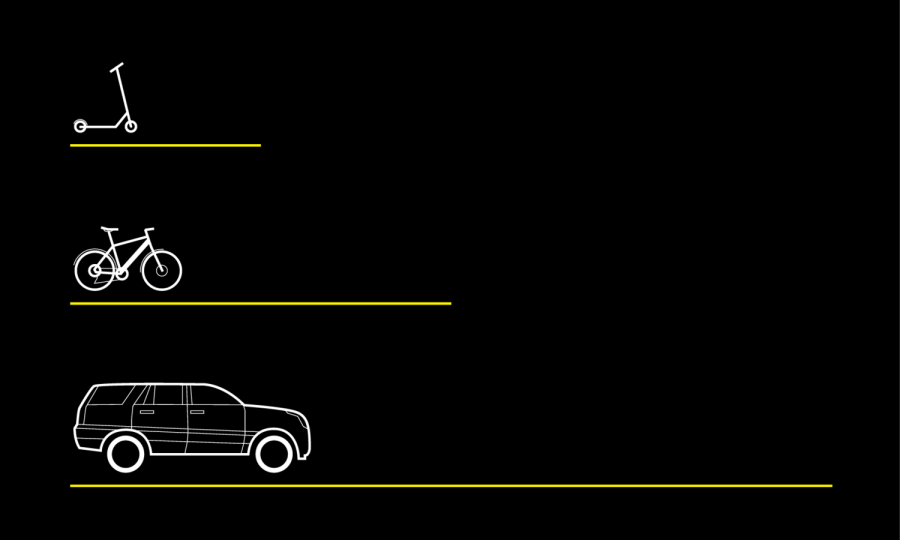

The scooters are a harbinger of a larger transportation movement called micromobility.

The central idea of micromobility is that we use cars when we don’t need to, simply because there are no better options — yet. Micromobility aims to shift our reliance on private cars to communal, bike-sized or smaller electric-powered alternatives.

Read more:

What the Sighted Don’t See

Mandatory Mindfulness

Impostor Syndrome in Computer Science

According to the U.S Department of Transportation data, 60 percent of car trips taken in 2017 were less than six miles long. Most people don’t have the time or energy to walk a six mile trip, or even one or two, but on a 15 mph electric scooter, all these distances could be covered in under 30 minutes.

The movement has its limitations, though.

There’s an implied minimum physical ability requirement to ride electric scooters, as you probably wouldn’t put your elderly grandparents or someone with an injury on one. Due to their single-rider nature, it would still be easier to drive kids to school in a car rather than send them on a scooter caravan. There’s also no place on them to put shopping bags or groceries, so people with baggage will need to find alternatives. They’re less appealing of an option in inclement weather. Then there’s the whole issue of making the scooters profitable while also keeping prices low. And, finally, the big one: infrastructure. At UCSD, it’s quick and easy to get around our mostly pedestrian campus on an electric scooter. But what if your short six-mile trip includes freeways?

Still, those invested in micromobility believe wholeheartedly in the cause. The inaugural Micromobility Conference took place in the Bay Area just this past January. The conference, which will take place in Berlin later this year, brought entrepreneurs, engineers, business leaders, government officials, venture capitalists, and academics together to reclaim cities for people, not cars.

The car industry has taken note. In late 2018, rideshare giant Lyft piloted Lyft Scooters, and auto manufacturer Ford Motor Co. acquired scooter startup Spin for $100 million.

The future of e-scooters holds a lot of promise, as they’ve already proven to be more popular than any other mobility device that came before. But to continue on an upward trajectory, companies will have to start doing more than just releasing scooters into the streets.

After all, motorized scooters aren’t new: Segway was introduced to the market in 2001, but was quickly relegated to a realm of tacky tourist activity. And who could forget hoverboards, the hottest trend of 2015 that became obsolete as soon as the novelty wore off?

Amidst all this micromobility publicity, the skeptics were quick to remind me that walking is still an option.

“I don’t feel like I have a need for it because all of my classes are very central, around [Center Hall]. I’m never in a rush to get anywhere so I never want to pay to get anywhere faster,” Beebe said. “I don’t even have the app and I never set it up because it’s not part of my routine.”

“You could use the shuttle, too,” Paris said.

There are also those worried that we are diving in too quickly, without giving proper thought to whether existing infrastructure could support e-scooters and place regulations on their use. In fact, many cities have begun banning the scooters because of potential hazards from reckless use.

A preliminary Google search for “electric scooter accidents” generates lots of concerned headlines, alarming statistics, and even an advertisement for lawyers billing themselves as “Electric Scooter Accident Attorneys in Santa Monica.”

Curious about potential legal recourse, I called Student Legal Services, UCSD’s legal counseling resource for registered students and organizations, and spoke to director and attorney Jon Carlos Senour.

Senour confirmed that, in the case of user accidents, electric scooter companies make it difficult to take legal action.

“The detailed user agreement that no one ever reads shifts all liability to riders. When you agree to that contract, you’re agreeing that you won’t sue Bird for Bird’s own negligence,” Senour said.

This means that any scooter company could shirk responsibility even for accidents that occur solely due to their equipment failing.

Complicating matters even further is the fact that equipment maintenance varies from scooter company to scooter company. Bird hires freelance mechanics of varying experience levels as independent contractors, whereas Lime has a dedicated street team of technicians. This makes tracking down who to pin negligence on even more complex.

After thanking Senour and getting off the phone, I checked the bus times and realized I was now going to be late to my 5 p.m. on-campus meeting. So I did what I usually do in this type of situation: I went outside, hopped on a Lime scooter, and zipped over to campus, rolling into my meeting with one minute to spare.

Photo courtesy of Micromobility Industries.

Karen • May 22, 2019 at 10:52 am

It is a nightmare, as riders dump them wherever they want when they are finished riding, usually laying them down on the sidewalks, with no regard for the disabled or elderly pedestrians. And unlike what the scooter companies suggest, the majority of the riders are tourists, underage children, and drunk college kids. Very few riders use the scooters as an alternative to their car; they use them as an alternative to WALKING.

Our local doctors estimate between four and six SERIOUS scooter injuries per DAY (requiring hospitalization), and we had our second scooter death here in San Diego County on March 15th.

There are also already at least four personal injury cases filed against the City of San Diego for their mishandling of the scooter situation. Those settlements will undoubtedly come out of taxpayer pockets.

Disability Rights California filed a class action lawsuit in January against the city of San Diego and three E-Scooter companies due to their inability to maintain sidewalk accessibility for the disabled.

https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/cases/montoya-et-al-v-bird-rides-inc-et-al

A friend of mine started his own YouTube page of scooter crashes taken from his balcony on the Mission Beach Boardwalk here in San Diego. Lots of “ouch” moments. Check out the one called Boardwalk Bedlam. Yikes.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCsN9bHroXuxz8UaANU6Eb5A