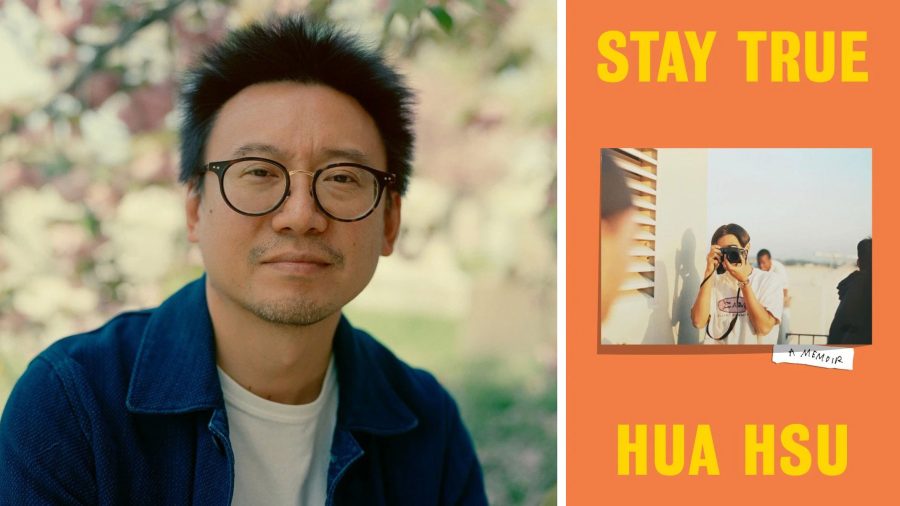

In an Attempt to Stay True

Jan 15, 2023

In a reflection on Hua Hsu’s memoir “Stay True,” A&E Senior Staff Writer Xuan Ly takes a deep look into her relationship with her close friend and how the memoir challenges her preconceived notions of soulmates.

In Greek mythology, Zeus split humans in two, fearing our potential power, and condemning us to an eternal search for a perfect half. From this myth arose the romanticism of soulmates. While many have taken the rigidity of this definition to heart, I have found solace in accepting that I may have more than one soulmate; in the idea that, for each stage of life, there could be someone with whom I inexplicably connect, whether platonically or romantically.

My thoughts about soulmates are rooted in the knowledge that people are constantly changing and refining their beliefs which can affect the nature of their personal relationships. Implicit in the acceptance of continual growth is the understanding that, for the most part, I will only know the people in my life within a particular context that is filtered through my own perception. For many of my best friends now, I came into their lives after years of experiences that I will never fully know about; and, I understand that they continue to hold and build relationships that I am not privy to.

This thought has never bothered me. In fact, I have always appreciated a certain degree of separation from many of my friends. But, as I read Hua Hsu’s recount of his friendship with his best friend Ken and the grieving process just a few years after their meeting, I was thrust into a state of insecurity that left me feeling groundless.

“Stay True” is Hsu’s debut memoir that made its way into the New York Times 2022 top 10 book list. In less than 200 pages, Hsu delves back into the mind of his college self — a self-proclaimed alternative thinker who constantly pushes the boundaries of contrarianism — his friendship with Ken, music, and Berkeley’s local history that accented Hsu’s adolescence. Even with an expansive range of topics discussed, what held my attention was the delicacy with which Hsu describes the small moments that formed his friendships.

Ken is seemingly the antithesis of Hsu: a fraternity brother from a well-adjusted Asian American family with a taste for Pearl Jam. Hsu is hesitant at first, never taking Ken as seriously as he does himself. But, through a series of small rituals and unspoken understandings, the two become close. Throughout the memoir, Hsu never explicitly explains the nature of their friendship, or the shift from friends to best friends, as though their connection was as inarticulable as that of soulmates. Instead, he focuses on their rituals: smoking cigarettes on the balcony, studying together at the same table in the library, making fun of users in right-wing chat rooms, curating mix tapes for late-night drives, and discussing old movies.

After three years of friendship, it seemed as though Hsu knew just about everything about Ken, especially as they saw each other mature into adulthood. Their bond felt like everything; or at least, it felt like enough. But, during Ken’s funeral, surrounded by strangers who held different connections to him, Hsu felt the scope of his knowledge shrink. While describing the funeral service, Hsu writes: “They referred to him as ‘Kenneth’ and quoted friends I didn’t know. I knew him in such a specific way, and it began to feel too small.”

Quite frankly, this line made me spiral. I thought about the little rituals I have with my friends and for the first time, wondered if it was enough. I felt a selfish and possessive need to know them more — to know them best. Even with my closest friend now, someone to whom I feel an unexplainable draw and with whom I spend most of my hours, I began to wonder how much I might be missing from her past and her future.

Like Ken and Hsu, we met in freshman year of college and connected relatively superficially over music and a shared Asian heritage. I cannot quite track how or when, but eventually spending time with her became part of my daily routine. I have always known that our time together is limited by school — even more so since she hopes to graduate one year early. But suddenly, this fact mattered over everything else. More than the excitement of her plans, or the pride in her continual success, or how just one year of friendship has felt like decades — only that with her growth, the specific way in which I know her could start to feel too small. I had confronted a hole in my beliefs of the transience of soulmates: I wished to keep my relationship with my soulmate the same forever.

But, I know this is impossible, and in truth, I would not want such stagnancy in life for either of us, especially during adolescence. So, I return to what I know now: watching rom-coms that make us sob, examining each other’s shelves for books to borrow, laughing at how long it takes her to find me in a crowd, a kiss on the cheek before we part. I remind myself of how she makes me better. Like Ken to Hsu, my closest friends have shown me who I want to be, have indulged me in my obsessions, and taught me to appreciate things I used to overlook.

Between the details of college life, Hsu makes conclusions about friendship that he has learned from time spent with Ken. One reflection stuck with me the most: “friendship is about the willingness to know, rather than to be known.” I know that in a year, maybe even less, my friendships will change. With the time I have with those around me, all I can do is learn as much as I can from them, carry it with me, and that will be enough.

Image courtesy of KQED

eva • Jan 18, 2023 at 10:52 am

Working part-time, I earn more than $29,000 every month. It’s still difficult to quantify, as I listened to a range of people describe how much money they would reasonably expect to make online. It everything turned out to be true, and it drastically altered my life. Everyone should utilize this website right now to

.

.

Try out for this job—————————————>>> GOOGLE WORK