A century-defining war is escalating in the Middle East, sparking massive protests across college campuses in the United States; the Supreme Court has yet to hear the end of the backlash for their decision to take abortion rights away from tens of millions of Americans; and a former president of the United States was declared a felon last week while maintaining his status as a presidential candidate. I say all this in an attempt to stir some sympathy within you, dear reader, as I have been prescribed the daunting task of — in the face of all that sexy political intrigue — getting you to care about the Social Security tax.

Social Security is an essential component of the American economy; it is responsible for keeping millions of Americans financially solvent in retirement and disability, including, hopefully, you someday. Given that a substantial chunk of your hard-earned money goes to keeping it afloat, you have a large interest in the future of Social Security; and you should know that the richest Americans pay barely anything compared to how much they make. This is not because of tax-dodging, loopholes, or any other kind of skullduggery. Rather, the government simply handed the benefit straight to the richest Americans. In other words: rich people have avoided their responsibility to contribute anything to Social Security, reaping the benefits and screwing the workers.

If you have a pay stub within arm’s reach, take a look. You will probably see an item labeled “FICA,” “Payroll taxes,” or “Social Security tax.” These are similar, except that the first two terms also include the Medicare tax under their umbrella. For this piece, we are going to put the Medicare tax to the side, but all of the arguments that appear in this piece can translate fairly smoothly. Currently, the Social Security tax is set at 12.4%, split equally between you and your employer. Oftentimes, though, employers pass on the cost of their payroll tax onto their employees via pay cuts, so employees feel most of the burden anyway.

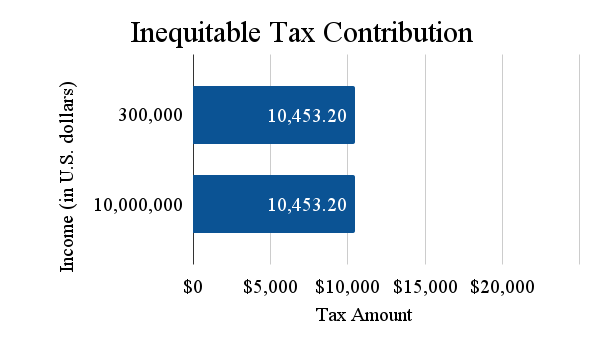

And there is one more catch: unlike the income tax, which is a progressive system based on paying into multiple tax brackets, the Social Security tax is deeply regressive — the more you make, the lower the percentage of your income you have to pay. Once you make more than $168,600, your effective marginal tax rate drops from 6.2% to 0%. Every penny made above that line waltzes into a bank account with no Social Security tax — a free break for the wealthy, no offshore Cayman Islands accounts required. Someone who makes $168,600 only pays $10,453.20, 6.2% of their income; someone who makes $300,000 only pays $10,453.20, 6.2% of their first $168,600; someone who makes $10 million still only pays $10,453.20, which is currently just enough to buy a used 1994 Jeep Wrangler. If God himself were to come down from heaven and declare that he made an infinite amount of money in 2024, he would only be required to pay a measly 1994 Jeep Wrangler’s worth of money towards keeping Social Security solvent. And unfortunately, the problem is getting worse. A congressional report found that because of rising income inequality, the percentage of income that escapes the Social Security tax nearly doubled from 1982 to 2021, even though the number of people who fall into this exemption has stayed the same.

Some people say this is fine. Rich people don’t need Social Security benefits, after all (although collect them they still do). A flat tax would be unfair, they say, because then rich people would be (gasp!) subsidizing the poors. And, sure: in an alternate universe where Social Security exists for some reason other than making sure that retirees and disabled people don’t get thrown into the streets, that reasoning might make sense. But Social Security isn’t a piggy bank that enforces responsible savings practices; it’s responsible for ensuring financial security. It is, by definition, a welfare program. That means curbing the excesses of the rich instead of rewarding them.

The simplest solution is to just eliminate the cap. But the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, objects. In a 1999 position paper, it said that eliminating the cap would subject “millions of American families to a massive hike in payroll taxes,” which conveniently ignores that all of those families are in the top 6% of income earners. The paper also says that eliminating the cap would only have postponed a future insolvency by six years, but conservatives cannot have it both ways: either the reform constitutes an earth-shattering amount of money or it does not. The Social Security Administration projects that immediately eliminating the cap could buy the fund 20–26 years, which is substantially more than six, so eliminating the cap is not some world-destroying tax on all Americans, nor would it prove to be ineffective.

The foundation also frets that such a tax would stimulate “negative feedback” in the economy. Conservatives have long contended that higher taxes kill the economy by reducing demand, although curiously, they generally only raise this argument when rich people’s dollars are at stake. But we can remove the cap without raising taxes at all by transforming the cap into a minimum: exempting the first $25,000 or so made by a worker from payroll tax instead of doling out those benefits to the richest Americans to compensate for the tax hike. In fact, since it stimulates the economy more to give money to poor people, as opposed to rich people who are incentivized to save rather than spend, Social Security could pocket a modest benefit and fix its regressive tax system. Seemingly, the only reason we don’t do this is because some people’s notion of fairness involves letting rich people line their own pockets in tax breaks, and then letting them collect their retiree checks on top of it.

Social Security is the strongest surviving symbol of the Franklin D. Roosevelt era, the ideological birth of the welfare state. At a time when the country faced a deep depression, Americans came together to make sure that some of its most vulnerable would be taken care of. It is, admittedly, not chic or sexy to care about administrative state reform in the current political climate. But the ever-presence that lets government work hide in plain sight also justifies the continued importance of that work, and the imperative to continue trying to reshape it to be more just and fair.