Namesake projects are typically inductions or re-inventions deeply intertwined with an artist’s identity. By nature, they are internally focused, brimming with confident declarations and serving as a time capsule in the creative journey. With his fifth album, Greg Mendez adds a self-titled record to his catalog. Yet here, on “Greg Mendez,” Mendez is only visible in vignettes, in small bursts of heartbreak inflicted by several shadowy figures looming over him. Across the entirety of his self-titled album, the man behind it is a slab of clay without a mouth. He is shaped by the hands of ex-lovers, addiction, friends, parents, and is never given the agency to ask why his creators have done what they have done to him. Across nine tracks, questions of self-worth pile on like flies to an open wound, but his bullish heart keeps pulsing.

The album’s artwork gives insight into the unrequited dynamics within it. The album cover is a religious figure in prayer: open palms and gaze transfixed upwards. Prayers are asks that fall on deaf ears, desires cast into the intangible where confirmation is impossible. All of the figures in Mendez’s past are divine in this way; he will ask and ask for answers without any acknowledgment. These repeated tragedies chip at his soul, shaping someone who wishes to be soft into someone harsh.

“Sweetie” succinctly encapsulates this transition from loving to guarded. The song captures Mendez’s relationship with love where we encounter two figures from his past: an ex-lover and his mother. Over a soft organ, it opens with the line “I won’t love again, after you.” It’s the end of a relationship, talking to a lover he can’t convince to stay. Shortly after, the song is perforated with a reference to his mother, and culminates in a line about her: “I wished she would say / ‘Sweetie, I’m gone away ‘cause I don’t love you.’” These two characters, his mother and leaving lover, are unable to stay. The absence of love is not necessarily the source of Mendez’s sorrow; it is the compounding factor of the absence of knowledge. He wants to know how two people who love him could suddenly leave him. But in their absences, there is no one to answer him. To cope, he fantasizes about gut-wrenching scenes where he is told he is no longer loved. If he is not soft enough for people to stay, he’ll become detached enough so that he won’t think of asking them to care.

However, Mendez appears to be all talk. He cannot completely withdraw from love, and the search for it almost resembles some aspect of self-harm. If love consistently wounds him, he’ll begin to search for pain. In “Shark’s Mouth,” he compares seeking and indulging in the company of his father to dumping buckets of blood in the ocean to be “caught in a shark’s mouth.” When he spends a night with him, Mendez writes to himself, “You never felt so scared to be alone / ‘til now.” Mendez knows that his father is a vicious figure, and he intentionally allows life-threatening proximity to him. But he chooses to search for him, to stay a night with him and face his brutality. At least here, cornered by the imposing figure of his father, he is acknowledged.

Conditioned to think anger and violence are to be seen, Mendez is timid in the face of innocence. On the stunning track “Maria,” he opens with, “Every time you say you wanna know me / I get anxious.” The idea that someone can approach him with kindness, that someone can be curious about him, is foreign. As a result, he turns meek and mild. In conversation with what can be assumed to be Maria, he awkwardly springs the story of a drug relapse in an attempt to engage in soft, intimate conversation. Here, he chronicles getting arrested after using again. He writes that he was clean for a while until he heard a voice calling to him: “Come back to me because it’s easy / … I’ll make you happy / … because I’m wrong.” When the people in his life did not offer solace and comfort, substance did. But now that he is clean and present, on the precipice of a relationship with Maria, he might find hands that can hold his awkward, heavy heart.

Evidently, the past weighs intensely on Mendez; it is his creator, motivator, and breaker all at the same time. On “Best Behavior,” one of the last characters on the album is unspecified. While the easy inference is an ex-lover, it could very well be a nod to a friend or parent. Regardless of who this presence was, they are no longer in Mendez’s life in the intimate way that they once were. The unnamed figure has got a “big new job,” and Mendez is sending photographic updates of his life. There is a palpable distance between them. Yet, still, this ghost of his past, molds him. He asks “I’m on my best behavior, do you like it?” Whoever this force once was, he wants to be good for them. There is a desperation, an ask of approval. Maybe if he is good they will return to him. However, like every other question he poses, it goes unanswered.

Only after sitting with “Greg Mendez,” digesting, and processing it, does the decision to self-title this album make sense. Here, Mendez is a religious figure because he is talking to his creators. Who are we if not the pieces of other people? Who are we if not the emotional products of our attachments? Those components of Mendez are undoubtedly heartbreaking but have all formed vital pieces of him. He is the product of his father’s rage, his mother and lover’s absence, his addiction, his hopeful acquaintances. On his fifth album, Greg Mendez is his past.

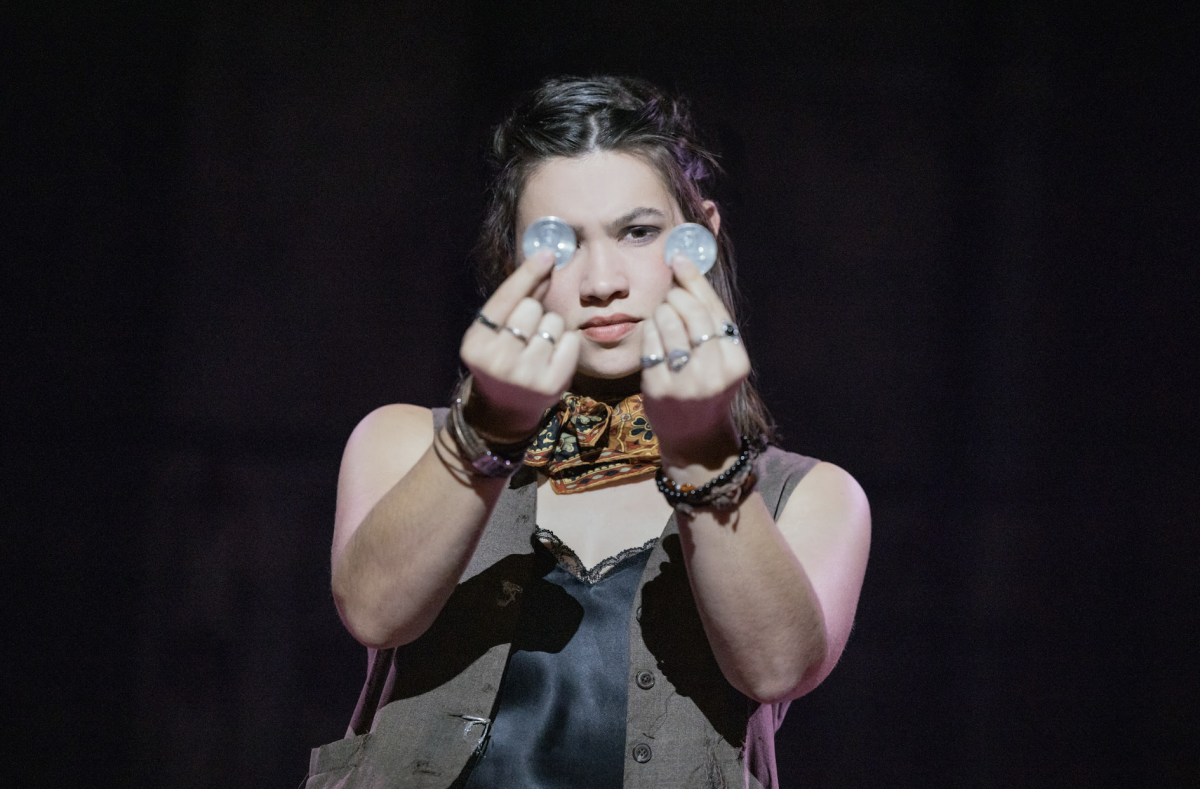

Image courtesy of Bandcamp