1957 was a year of genesis around the ever-changing world. In Sweden, Ingmar Bergman emerged as a leading voice in world cinema with his “Seventh Seal.” Sputnik I’s launch from the Soviet Union ensued a longstanding space race with the United States. A whole sport was birthed out of the burgeoning commercialization of the frisbee. Meanwhile in New York, there was a miracle due, who knows? Well, we know now, that it was the debut of Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story” on Broadway, which would skyrocket both into the mainstream.

Whilst Sondheim’s name would go on to be engraved in the murals of Broadway legend, the body of Leonard Berstein’s work has come to encompass the makings of the first great American composer. From renowned arrangements of Gershwin and Mahler, to beloved show tunes from “On the Town” and “Fancy Free,” to sparking the passion of musicality for many generations with his “Young People’s Concerts,” the maestro has become one of the most prolifically documented conductors of the modern age. Yet in the glamorization of legend, art always exceeds and lives on for eternity as the maker withers away.

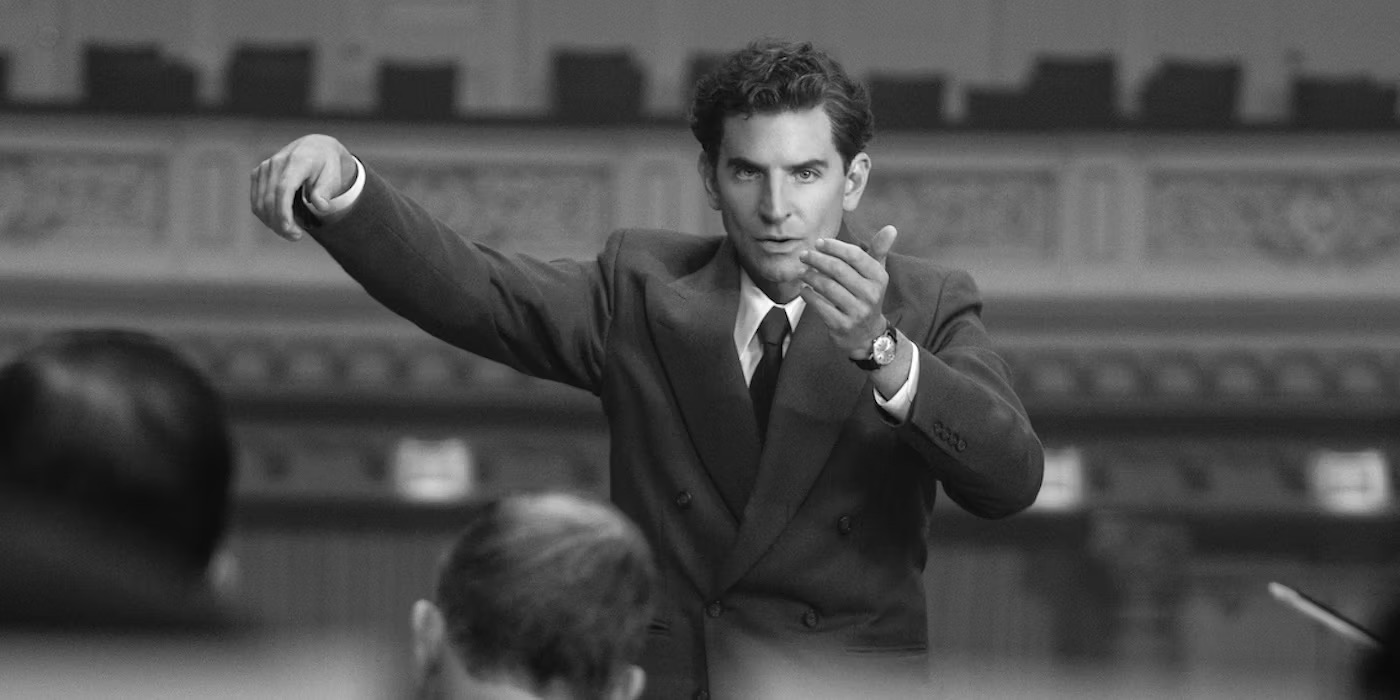

And so, Bradley Cooper’s “Maestro” (2023) attempts to reconcile these differences. Nominated for seven Academy Awards at this year’s Oscars, including Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Picture, Cooper’s romantic and sweeping dramatization of the famed conductor’s life recollects years and years of the love between Lenny Bernstein (Cooper) and his wife Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), as both rise to prominence in their respective worlds. Effectively eschewing the interplay between music and the personal, it hones in on small personal spaces, zoning in on the breakdown of the marriage through Bernstein’s constant flirtation and relationships with other men. One can feel that Montealegre is far stronger and better of a person than Bernstein deserves, it’s ever apparent throughout with Mulligan’s sturdy demeanor in spite of her deeply weighty and heavy eyes. And in witnessing Cooper as the man himself, one can gather together Bernstein’s charity and sweetness, but also a crippling inability to be left alone. It’s a performance that takes big swings, and sometimes reads as too studied and too emotive, but the earnestness is admirable.

Cooper and cinematographer Matthew Libatique capture Bernstein’s life in monochromatic color as well as warm autumnal frames, utilizing a 4:3 aspect ratio to create a cavernous feel, such that the space of his life was always large. It’s fascinating to watch the shot composition spiral from sweeping epic scale, to diminuendos into a sobering documentarian-esque feel. Whilst the color-bypass of the youthful Bernstein scenes remains unconvincing (in part due to the lack of true blacks in the color values), there are flourishes of surrealism and stage magic as Montealegre drags Bernstein by the hand, smiling and laughing, and that’s when Maestro is at its grandest, and its best.

The high watermark of Maestro arrives in the form of the Ely Cathedral symphony scene, which is a stunner. The scene in question, set to legendary composer Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, is a sequence bereft of dialogue, for it channels Bradley Cooper’s six years of studying Bernstein’s life into an expression of ecstasy and passion, with overwhelming sound design, all wrangled in by Mulligan’s expression of adoration and transcendence, reconciling the purity of Bernstein’s talent, that he’s fallible, but his art, and what he has to give to the world, is as kind and generous as they come. Many scenes in the film are tracked to Bernstein’s gorgeous compositions and arrangements, yet their beauty often feel translucent and obfuscated, being repurposed to serve a narrative, one that overwhelms with too much visual and didactic biopic information, rather than being allowed to soak in the mind of the observer and listener, where I feel Bernstein’s music is best experienced. However, in the halls of Ely Cathedral, Bernstein’s arrangement is given full room to flourish, rather than simply accompany Cooper’s staging, and the film becomes ego-less in this moment, unconcerned with the prestigious air it has built throughout the runtime, and becoming wholly reverent of the biblically-grandiose nature of Bernstein’s arrangements and skill. In this moment, it’s one where we finally know the one universal truth of Bernstein for certain: Lennie just had the passion for life.

Yet it is one of few brilliant glimpses in a rather rote exercise of form. The choice to stage the whole film as an examination of almost exclusively cardinal sin and loyalty bars us from witnessing much of the genius of Bernstein. And in doing so, Bernstein has become mortal, and we are to observe him as a man, not a myth. For all its kaleidoscopic ambitions, the interiority of Felicia and Lenny is close to hollow, as the conversations never break the surface, and the choice to exclude details of their professional life greatly damages our perception of these multifaceted people. Mulligan’s sadness is rendered with such an astute and flamboyant nature, but in the end, it’s as if I had known her for a minute, and not years. With retellings of the once-living, there’s no one way to truly capture their totality, and the subjectivity of their experiences is lost to time. We will always be reanimating ghosts without their souls, even if we try our damndest. I still can’t decide if Bernstein was someone great.

But I know that he tried to be.

Image courtesy of Collider