Two and a half years ago, when I watched the watermelon plunge to its much-anticipated demise, chucked gently by a male Watermelon Queen sporting pieces of rind in critical places, it dawned on me that this was the most UCSD students I ever saw congregate for an event that was unmistakably collegiate. And so it was, the next year and the one after that.

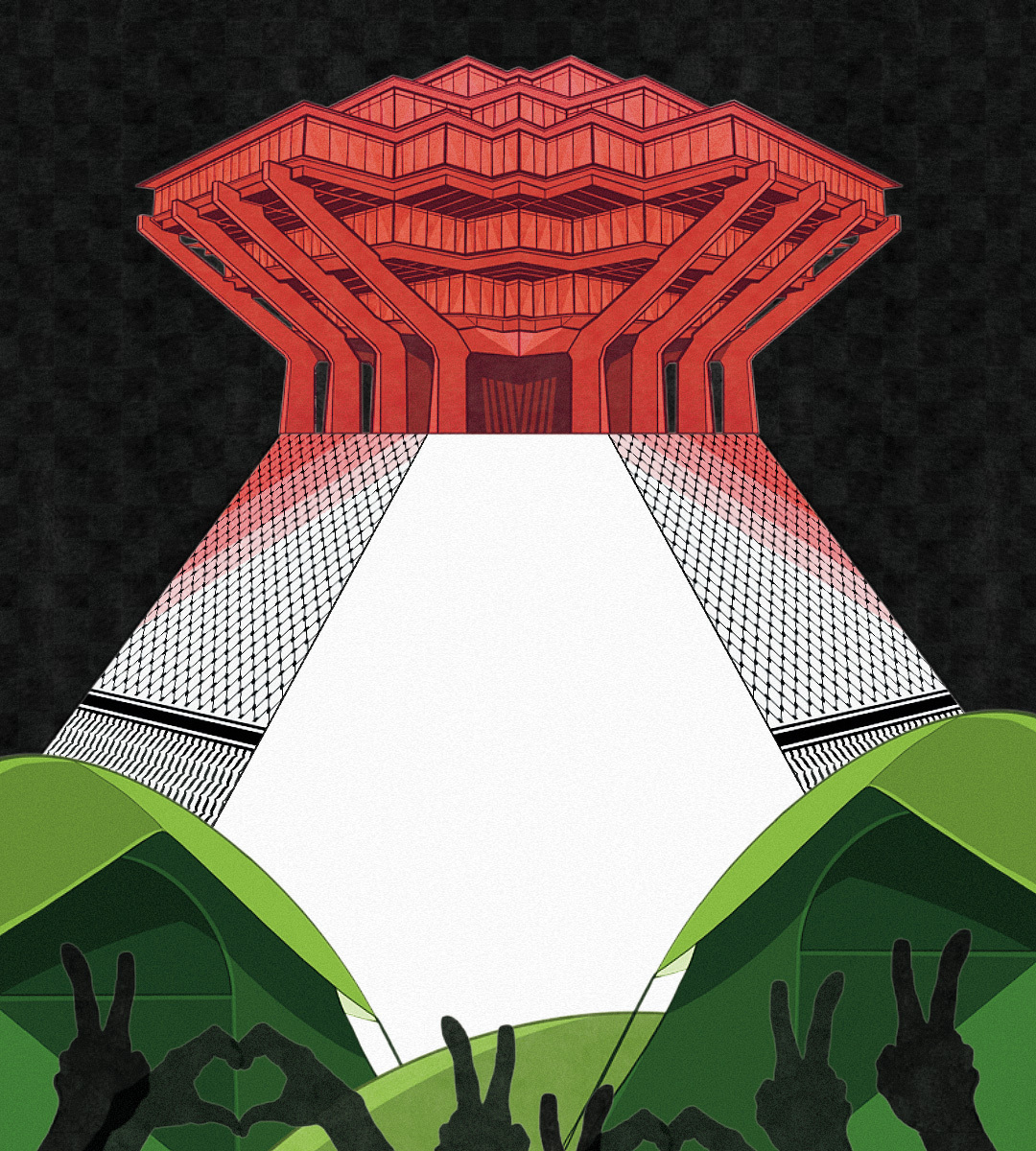

A distinctive campus spirit at UCSD is possibly the most significant deficit this powerful research university faces. Like the ideal young minds that attend, the character of UCSD is itself a tabula rasa. The next 10 years will reveal whether UCSD is prepared for cultivation or devoid of pride and spirit for want of the proper infrastructure.

This past fall, the Undergraduate Student Experience and Satisfaction Committee suggested a number of improvements (their report is available at http://studentresearch.ucsd.edu/satisfaction/). As extensive as the list is, however, it tends to linearize the problem, placing things with vastly different costs quaintly, albeit in some order, on the same scale. Rather, there is one very expensive project that UCSD must complete over many years and a variety of inexpensive rearrangements that it can complete immediately.

Costly is a vast increase in the on-campus housing that would make UCSD less of a commuter school and more of a four-year university. The construction of the beautiful new ERC apartments, housing 1240 students, is a step in this direction, but only if the on-campus housing grows in proportion to the student population. Sophomores, seniors and, most importantly, juniors have to be kept on campus in order to create a mature academic culture.

In creating a single, large public space in the new ERC apartments, architect Moshe Safdie has in fact provided the college residence with an ideal place for community events and college functions. This is precisely the plan of all nine colleges at my alma mater, Rice University, and an achievement for its $106 million cost (while I was there, Rice spent $60 million to build an equivalent outfit for 320 students).

Like stem cell therapies on the horizon, students must be coaxed to adhere and flourish in places that make our society healthy — this would be expensive, but a real bargain compared to the $3 billion Gov. Schwarzenegger helped procure for my metaphor’s inspiration. The one-time investment in housing would likely also be a minor expense compared to the annual buckets of financial aid — needed as they are — that the university expends.

One inexpensive measure would be to restructure college governments and bolster their coffers. At Rice, each of the nine residential colleges consisted of roughly 300 students. Their operating budgets, roughly $35,000 per annum, each paid for at least two major parties, annual theater productions, weekly meetings of the governing body, special occasions for seniors as well as underclassmen, service projects, freshman orientation, study breaks and the most significant campus event, “Beer Bike” (Google that — you are feeling lucky).

The same formula is largely in place at UCSD’s residential colleges, with some significant differences. John Muir College, for example, occasionally sends students on day or weekend skiing and theme-park trips. When all UCSD colleges are larger than the nine colleges of Rice combined, it becomes economical to do bigger things; however, relatively expensive trips that send students off campus should be weighed against activities on campus that every student could potentially attend.

Another bargain fix would be to restructure freshman orientation. This is not something that should take place during a weekend in the middle of the summer — the introduction to college life should occur in consecutive steps.

At Rice, freshman orientation is a week-long event that takes place immediately before the academic year, permitting freshmen to fraternize before upperclassmen and problem sets descend upon them. Aside from the bare-bones information sessions provided by UCSD colleges, Rice University’s “O-week” provides time for freshman to meet their college masters, talk with student mentors to plan their first semester, and experience mild forms of hazing.

The faculty masters are generally aware of what is taking place, but the atmosphere remains safe because alcohol is strictly prohibited during O-week. College masters participate with students to plan events for the incoming freshmen, but rarely have to rule: Playboys and partiers get balanced out by mother hens and achievers, and problem themes such as “Home DepO-week” (when freshmen might get “hammered” and “nailed”) are often tossed out by students before the masters have to step in.

Alcohol and drugs are a darker facet of campus spirit. The president’s office at Rice frequently defends its “wet-campus” policy against angry parents who want the university to enforce morality when they are no longer able. There’s no way to put a price tag on any changes to the current UCSD policy. However, there are a lot of points in the Rice policy that contrast favorably to that of UCSD. Rice police assured the students during O-week and at other times of two things: that they would not enter a room to break up a private party (an unwritten rule that extended as far as patios and stairs), and that calls concerning alcohol poisoning summoned only an EMT to treat the patient (not a policeman to question the people involved — that was done later, by the college masters). Students occasionally sat down with police officers for breakfast or lunch.

Rice RAs were typically university staff (although faculty sometimes applied) that served seven-year terms, and unlike UCSD RAs, they were primarily resources for the students — they never checked rooms. The rationale for this policy was that it kept drinking on campus, where students could walk home or summon EMTs quickly in an emergency.

This is about much more than just making students feel better about the place they went to school, boosting grades, preventing DWI or providing a fuller college experience. David Brooks once opined in the New York Times that, for all their liberal social views, academics are failing to give the nation’s poorer classes a chance at higher education. It is as much a cultural barrier as a financial one that keeps them out and impedes their progress if they get in. A distinctive character on campus outshines social differences, advancing productive enthusiasm over established fortune. Campus spirit is a strong indicator of UCSD’s commitment to building a society based on merit rather than birthright, and therefore an indicator of its service to America.

I mustn’t mention too often that I went to Rice — although I never refer to it as “the Harvard of the South,” that reputation’s gotten around and my students sometimes roll their eyes.

I also can’t mention too often that I went to Rice — I am immensely proud of my years in college and love my alma mater. Students at UCSD should feel just as proud — on this cliff sits an up-start university that does world-class research in science and social issues, presides over miles of beaches, sports a respectable art program, and attracts influential speakers from almost any discipline.

The thing UCSD lacks isn’t any particular character but a distinctive character. Like memos in a corporation, college spirit is the lifeblood — or the embalming fluid — of an undergraduate program.