On Oct. 16, Ocean Vuong arrived at UC San Diego to participate in an hour-long discussion of genre, Buddhist philosophy, and persona with literature professor Lily Hoang. I managed to secure a seat at the front of the amphitheater right as another literature professor, Kazim Ali, humorously introduced the renowned author and poet. The crowd’s eyes immediately fixated on Vuong and Hoang, who was dressed in a beautiful áo dài, and never broke away.

Vuong opened the conversation by reciting his singular 2024 poetry composition, “16,” a timeless tapestry of death and family where the speaker is a 16 year-old attempting to imitate 16th president Abraham Lincoln. The poem is staggeringly beautiful throughout, but what stuck with me the most was that — in the midst of his imitation of Whiteness — the speaker calls out the names “Lan, Phuong, Linh, mẹ.” At once, it reminded me of how writing and poetry, in particular, is not anonymous. Writing, as an avenue, allows for the expression of explicit identities and gives them space in the world.

It also reminded me of home.

Something that I found particularly striking about Vuong’s conversation was how the famed poet illuminated the bi-directional beauty of art — in service of community and being true to oneself. Art is both universal and intensely individualistic.

Several times throughout the discussion, Vuong mentioned a “North Star” that guides him, whether in the form of the feeling of wonder or the philosophical teachings of Buddhism — like the Eightfold Path or following the Bodhisattvas’ goal of rejecting enlightenment to stay with the suffering. In the same manner, I’m certain that Vuong’s works have served as Polaris for many of us in the audience, at least at once, unifying us in our hopes and dreams.

We also come to understand that Vuong is concerned more with understanding himself than with boxing his voice into the hallmarks or platitudes that come with writing in “genre.” He admitted that, while he’s still grappling with how to “write for [himself]” in the wake of his mother’s passing, he must still write to give himself to others and, more importantly, to be himself. Otherwise, how else would our gift to life be distinguishable from that of others?

We exist in a time when focus groups and fandoms have become the arbiters. We’ve commodified films and shows and books and music into terms like “content” and “media” that debase their value and connection to humanity. It was deeply heartening to be reminded that our work is not just another crop in the farm of content and that your ideas and dialogue in the world are invaluable. The reconciliation of community and individualism, for Vuong, exists in the notion that the personal can be universal, but if the universal becomes the personal, our hearts will be lost in translation.

Throughout the discussion, the crowd was moved to tears. More than a few of my friends left with a heady feeling of introspection after the matter. While leaving the amphitheater, one thought crossed my mind: Ocean Vuong exists outside of bounded time — not in a physical sense but rather, a conscious one. Vuong, throughout the dialogue, lambasted the West’s obsession with the concreteness of organization, deriding the solidification of vocation, of destination, and of the need for art to have started and ended.

Perhaps we obsess over the finite nature of objects because it’s easiest to know when suffering starts and when it ends. But in that suffering lies community, bonds, and finding our way home. We bear our scars and trauma on our body; we are still discovering ourselves every day, and until the end of our time — whenever that may be — we’ll take pride in experiencing who we will become forevermore.

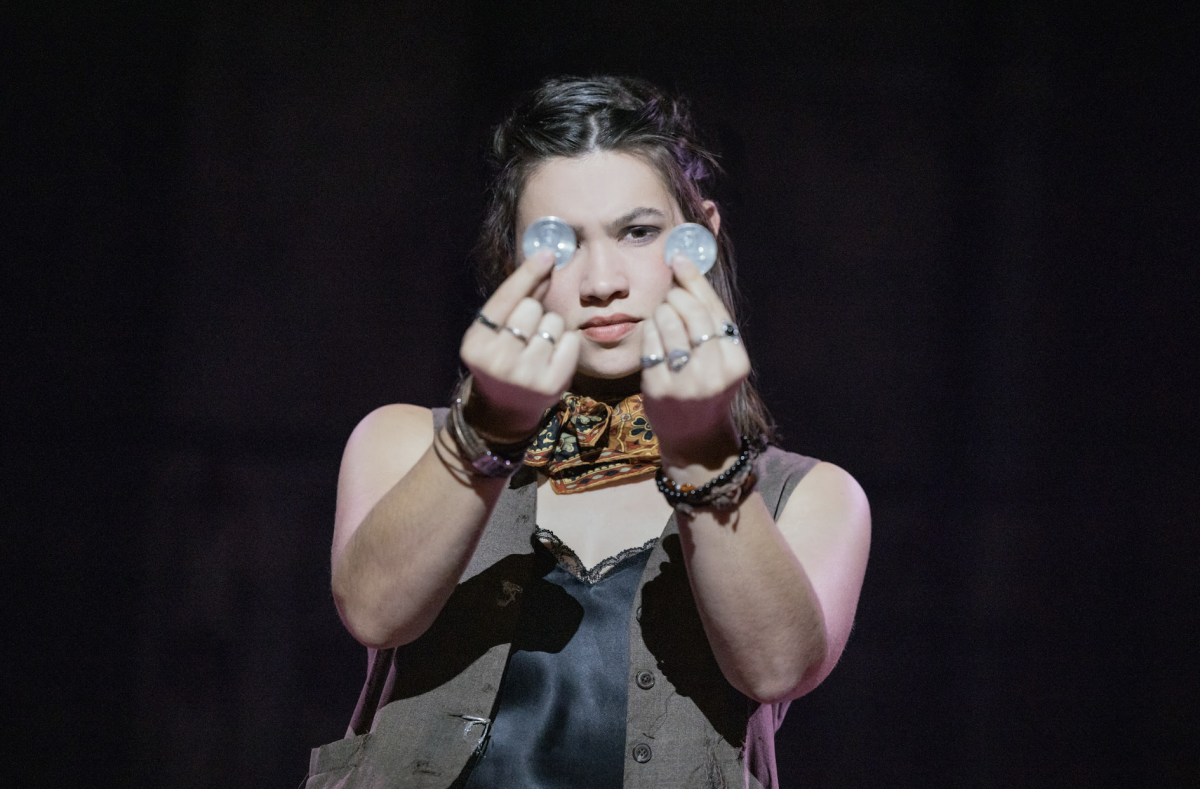

Photo by Michael Ho for The UCSD Guardian